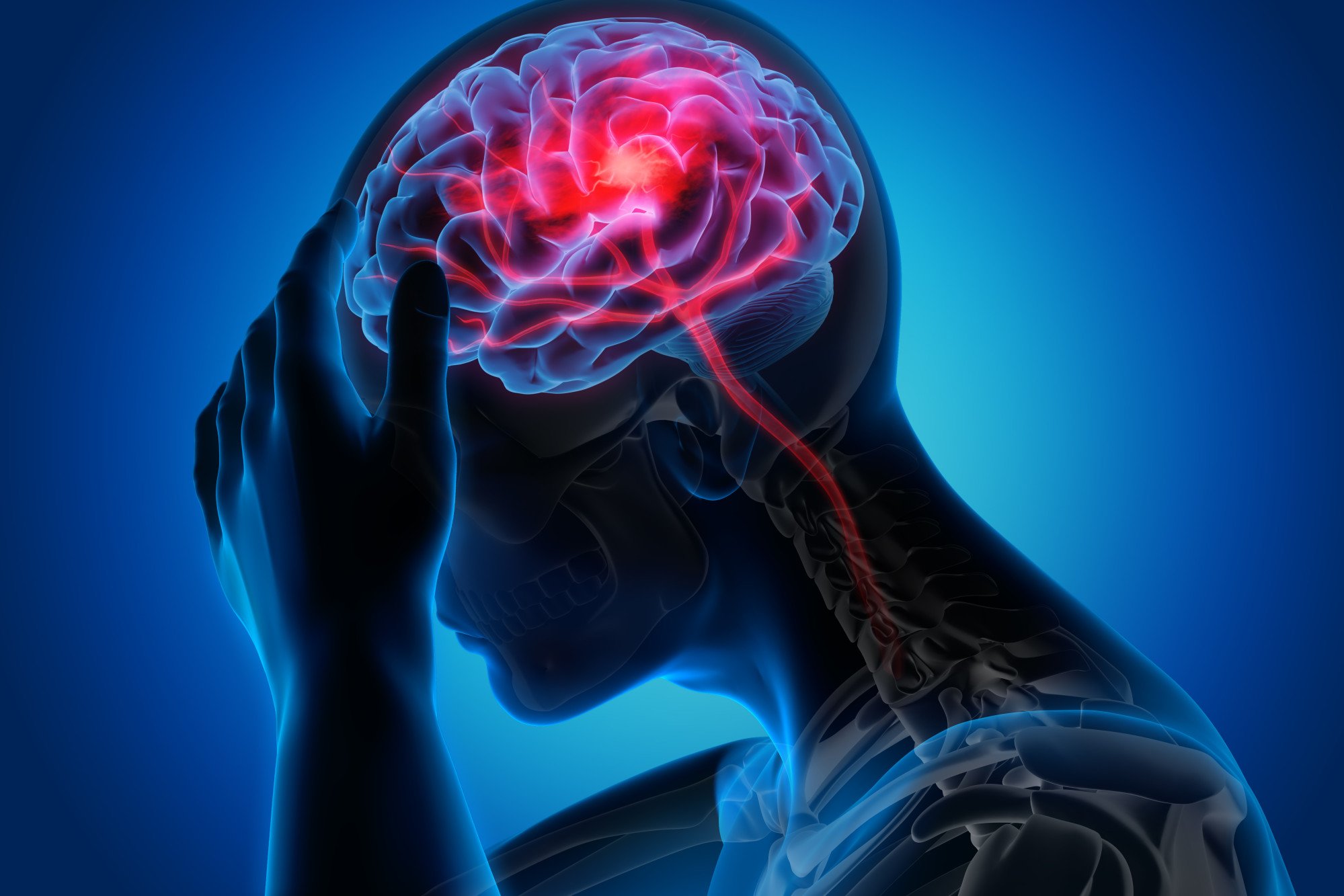

How a stroke raises dementia risk in the short term, and for decades afterwards – losing the ability to read, or speak, causes social isolation

- One in four people who have a stroke develop dementia, as neural damage causes cognitive loss that can reduce social interaction and intellectual engagement

- Unsurprisingly, the risk of dementia triples for three to 12 months after a stroke, but research has found that the risk persists for up to 20 years afterwards

When my mother had a stroke four years before the first signs of dementia were visible to us, she lost her ability to read.

After her stroke she developed a rare condition called pure alexia – acquired reading impairment without losing the ability to spell and write; she went, overnight, from being able to read words on a page to not being able to fathom a single one.

“This is all rubbish,” she announced. It was the only sign of stroke that she exhibited outwardly.

One in four people who suffer a stroke go on to develop dementia. And one in four people will have a stroke in their lifetime.

Sometimes the risk presents soon after a stroke. “We found a three-fold risk of dementia between three and 12 months after stroke,” Raed Joundi, a neurologist at Hamilton Health Sciences and assistant professor at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada, said.

The presence of a higher risk of dementia soon after stroke isn’t that surprising, he says.

“There is a direct brain injury from the stroke, which can impact cognition and daily function,” he says, and because the patient is likely to be under close medical observation – my mother was in hospital for three weeks after her stroke and a rehabilitation centre for three months after that – any changes in cognitive function are noted quickly.

The more surprising finding of the research was “that the increased risk of dementia persisted throughout 20 years of follow-up, so there are many indirect mechanisms that may be acting long-term to promote a higher risk of dementia years after stroke”, says Joundi.

Losing important functions like reading, speaking, or communicating may promote sensory and social isolation ... this may make individuals more susceptible to dementia

The dementia risk soon after stroke may be due to direct injury to parts of the brain that impact cognitive function; lesions that cause difficulty with language and performing tasks are more highly associated with a dementia risk.

“This includes the thalamus, left frontotemporal lobes, and right parietal lobes. Lesions that cause aphasia (difficulty with language) and apraxia (difficulty with performing tasks) are more highly associated with dementia,” he says.

My mother’s stroke interfered with her visual perception of letters and as a result she battled with written language.

Bruce Willis’ dementia diagnosis: what is FTD and how to spot early signs

The enduring long-term risk is probably due to an acceleration of age-related and neurodegenerative pathways, as well as neuro-inflammation, Joundi explains.

When I describe my mother’s experience of stroke, Joundi says that this could be one of the important ways dementia risk is elevated after stroke. Social activity and intellectual engagement can slow the progression of dementia.

“Losing important functions like reading, speaking, or communicating may promote sensory and social isolation and decrease the amount of social and intellectual stimulation.

“Eventually this may lessen cognitive reserve and make individuals more susceptible to the onset and effects of dementia.” Cognitive reserve is defined as “a property of the brain that allows for better than expected function given the degree of adverse brain-related change”.

Research by a team at University College London found that reading the newspaper might reduce the risk of dementia in women by 35 per cent. The women monitored were from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, which includes people born in or before the 1950s.

Lead author Pamela Almeida-Meza says: “At the time, there were few women in higher education or senior positions at work, but many were self-educating, which had a positive impact ultimately on brain health.”

How to help the elderly cope with lockdown anxiety, loneliness

Those things conspired to cause a loss of self-esteem and independence which drove the isolation further.

Dr Emily Rosenich at the University of South Australia says that while research on cognitive reserve in the context of stroke is not completely understood, preliminary evidence suggests it has the potential to influence stroke outcomes and recovery.

After all, how do you explain how people recover lost ability post-stroke so that they are able to talk again, walk or swallow; or to read – albeit much more slowly than before.

So why did my mother’s cognitive reserve – which seemed to sustain after stroke for a bit so that she got some reading back – not withstand the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease later?

If messages managed to circumnavigate the area of her brain damaged by the effects of stroke, why did that neural re-routing – that compensation – not grow more robust with practice, not get more efficient and not last?

The effect of stroke lasts long after the stroke itself, due in part to the “acceleration of age-related and neurodegenerative pathways”, Joundi says.

As my mother’s doctor explained, cerebral blood flow in stroke is interrupted or impeded – and vascular health is as important for our hearts as our brains.

Add to these the physiological insults of stroke, my mother’s immediate loss of fluency in reading and a subsequent growing isolation from the world because she could no longer read with ease or speed.

She didn’t write, which meant she lost the ability to communicate with those she once enjoyed corresponding with by letter or email.

Her stroke didn’t just impact her brain at the time of her stroke, but also caused a sort of catastrophic leaking of precious cognitive reserve: a brain drain.