Explainer | How the vagus nerve – body’s multilane messenger from our brains to our organs – is used to manage conditions from epilepsy to migraine

- The vagus nerve is a complex system helping to orchestrate and regulate many of our bodies’ vital functions, from heart rate to digestion and blood pressure

- Interest in improving its function, or ‘vagal tone’, has exploded; the hashtag #vagusnerve has attracted more than 153 million views on TikTok

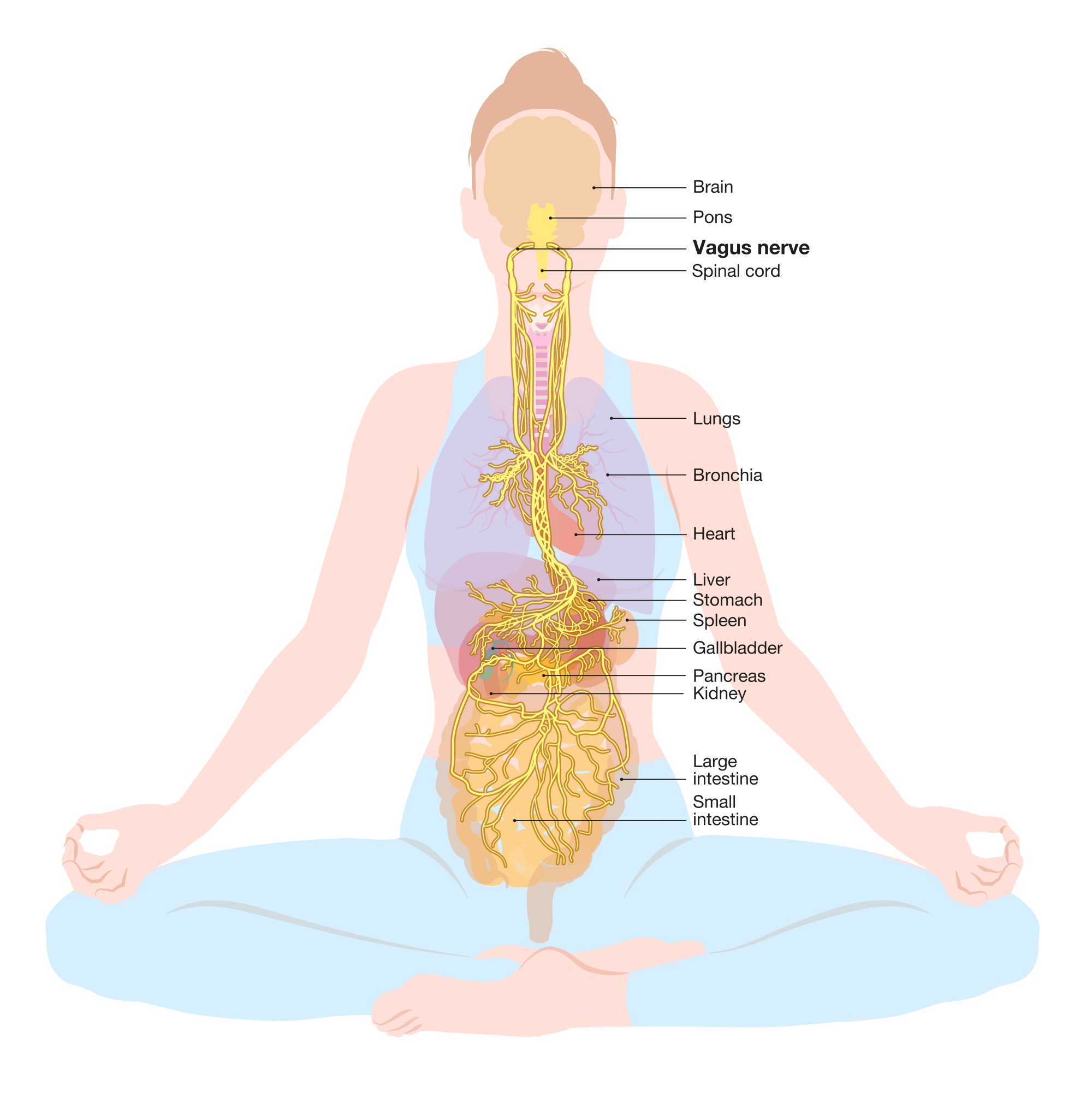

The vagus nerve – which runs down the body from our brains to our large intestine – is the 10th, and longest, of 12 paired cranial nerves that send electrical signals between our brain, face, neck and torso.

The vagus – from the Latin for wandering – nerve threads a complicated route through bodily systems that affect digestion, heart rate, blood pressure, mood, mucus and saliva production, skin sensations, speech and taste, to name a few. Its presence is felt almost everywhere.

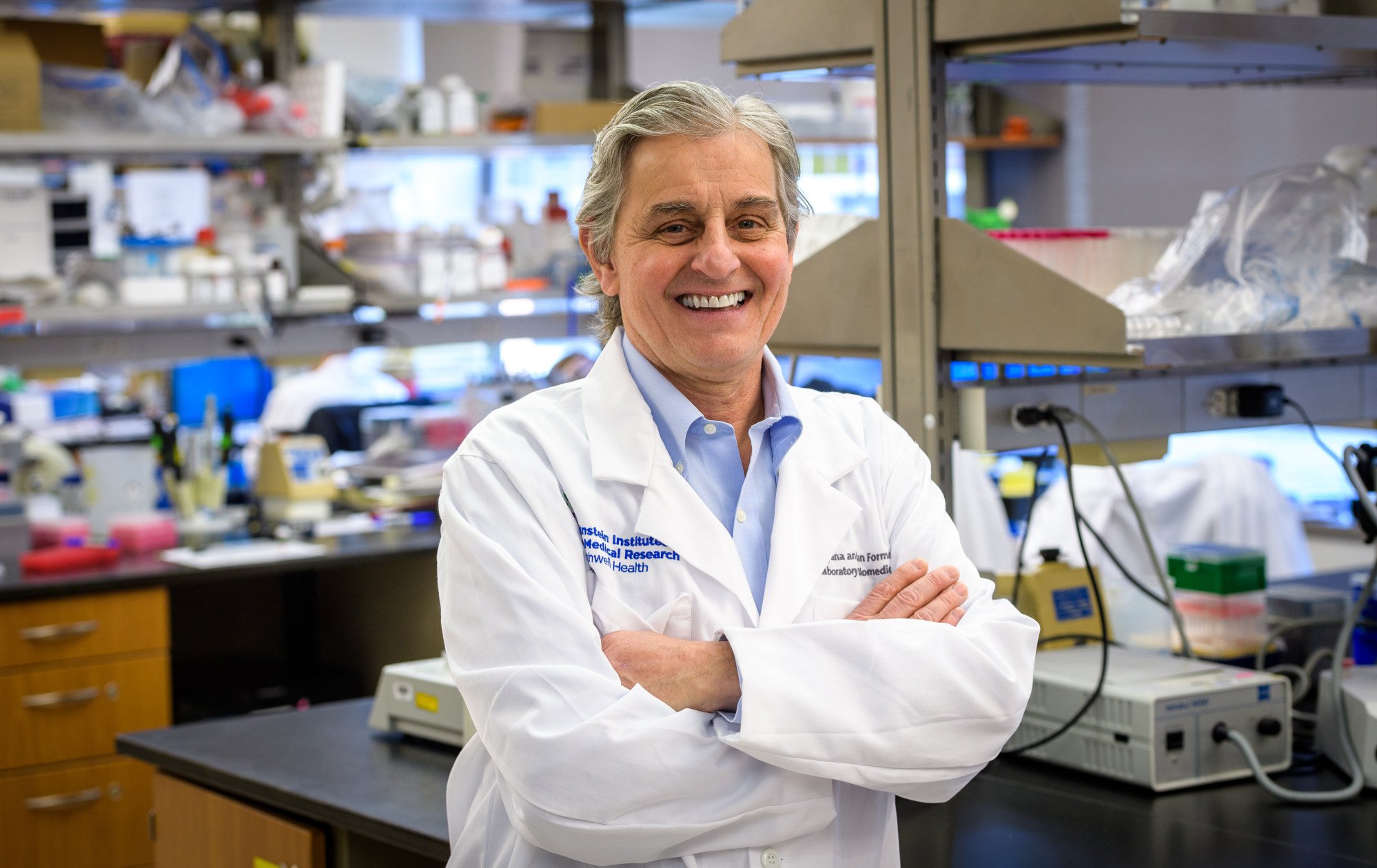

Professor Kevin Tracey, a neurosurgeon, and president and chief executive of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in New York state, is at the forefront of the science surrounding the vagus nerve.

“People tend to think and talk about the vagus nerve like a single, solid copper wire, but it’s more like 160,000 wires, each of which can control a very specific function,” he says.

The power of this specificity can be difficult to comprehend, but a simple example is that most people can walk and chew gum at the same time, without thinking about either, says Tracey.

“Similarly, the vagus nerve is doing complex parallel processing, controlling all the organs we never think about.”

Your gut affects your mental and physical health; here’s how to optimise it

Dr Daniel Ko is the chief executive and founder of Hong Kong start-up Neuropix. It has developed wearable wireless nerve stimulation devices that help manage neurological disorders by rebalancing patients’ brain chemistry.

Ko describes the vagus nerve as “a neural circuit that regulates key physiology including heart rate, gastrointestinal motility (the ability of intestinal muscles to contract), pancreatic secretion and glucose production”.

In other words, it helps orchestrate the vital unconscious efforts our bodies make to sustain life. Not for nothing has it been called the body’s superhighway, and not just because it carries crucial information between the brain and the internal organs.

It also controls the body’s response in times of rest and relaxation..

The earliest evidence of this extraordinary nerve dates back 2,000 years to when Galen – the leading doctor of the Roman empire, who discovered the difference between arterial and venous blood – accidentally sliced through the nerves in a pig’s larynx.

The animal stopped squealing but continued to wriggle. As a result of this fortuitous (for us, less so for the pig) finding, Galen also played a significant part in developing human understanding of the nervous system.

What causes epilepsy, what triggers a seizure and what treatment is there?

Because of the role it plays in so many automatic functions, the vagus nerve, Ko says, lends itself to therapeutic application. Invasive vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) was approved by the United States’ Food and Drug Administration in 1997 for drug-resistant epilepsy.

Thirty per cent of epilepsy sufferers struggle to control their condition, so VNS has proven life-changing for them.

It works by sending electrical pulses to the vagus nerve, which transmits those pulses to the brain and helps minimise the severity of seizures.

In all these cases a small device is either surgically implanted in the chest cavity near the collarbone or, more recently, worn as a portable device on the ear – the vagus nerve starts between the carotid artery and the jugular vein just below the ear.

The device Ko’s Neuropix designed – which looks like an ear pod – is an example.

Breathing deeply and steadily is like gently easing your foot down on the brakes of a car that is hurtling out of control; it slows and stops inflammation.

What’s the key to better sleep and less stress? It’s how you breathe

“Cut the vagus nerve,” Tracey says, “and inflammation will race out of control. Over millions of years, evolution selected the vagus nerve to be the brakes on inflammation, because nerves transmit information quickly, and have the capability of coordinating, across time and space, complex processes like inflammation.”

VNS is an example of the manipulation of our physiology for better health using an electronic device, like Ko’s Neuropix. It joins what Tracey calls the “new world of bioelectronic medicine” – which may lead to better clinical therapies for a number of health issues, not just epilepsy.

People who exercise regularly, have healthy diets and get enough rest tend to have slower pulse rates. And if your heart beat is slow, that’s a very good sign you have very good vagus nerve activity

Certainly many of these practices are good for us. They may help slow respiration, which in turns helps reduce stress and turn off the production of stress hormones which cause inflammation to rise.

But, as Tracey says, it’s a bit more complicated than that. This isn’t a single copper wire neatly bound at either end; this is a trailing spaghetti junction.

Some of what proponents say is based loosely on science, Tracey says, but much of what they recommend has yet to be subjected to rigorous clinical study with appropriate controls and analysis.

This prompts a decrease in heart rate and drop in blood pressure. This in turn causes the vessels in your legs to dilate, so blood pools there and doesn’t get to your brain quickly enough – causing you to faint.

How do you know if your vagus nerve is in top condition?