Hong Kong isn’t becoming an authoritarian state, no matter what the pro-democrats say

Take a step back and really assess the situation surrounding the banners being put up on university campuses, and the jailing of activists. Is it really the political persecution people claim it to be?

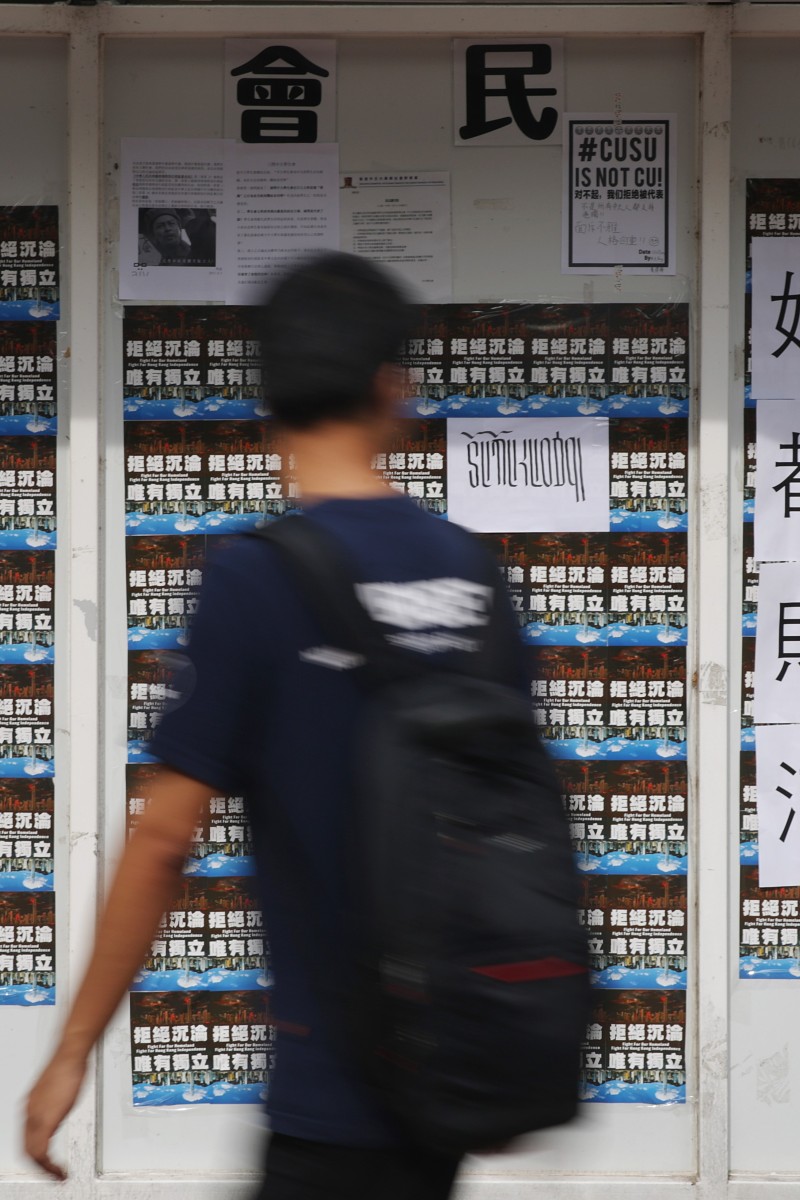

The fact that we can put up banners in the first place, and have “democracy walls” on university campuses, set us apart from countries where the government controls almost very aspect of public life.

The fact that we can put up banners in the first place, and have “democracy walls” on university campuses, set us apart from countries where the government controls almost very aspect of public life. The recent jailing of three Occupy student leaders and the removal of separatist banners from university campuses has led to claims of “political persecution” by the city’s pro-democracy camp. But despite their rhetoric, Hong Kong is far from becoming an authoritarian state with no regard for the rights of its citizens. Such talk, other than warping the reality of the situation, threatens to undermine the integrity of our independent judiciary, and trivialises the struggle of those currently living in despotic regimes around the world.

While some better-informed critics have moved beyond claiming the judiciary has been “bought out” by the Central Government (it hasn’t), their contention that the Secretary of Justice’s decision to appeal was tantamount to political persecution does not hold water either. In many jurisdictions, including Hong Kong and Britain, both parties in criminal proceedings are entitled to appeal against the sentence if it’s deemed to be manifestly excessive or lenient. This has been done as recently as May in Britain, and Hong Kong’s Department of Justice has previously appealed against the sentence for a truck driver who ran over an elderly woman. The appeals are within the scope of ordinary practice, a point that former governor Chris Patten conceded to be true. While the crime itself was politically motivated in this instance, the reasons for seeking a lengthier sentence were based on that their actions endangered public safety, not politics, as outlined in the judgement.

The problem with the allegations, protests, and the personal attacks against the judges that have risen from this case is that they ultimately undermine the integrity of the system. That judges are being personally attacked and threatened means that they face increased pressure to rule in favour of the opposition. Even with their robust training that helps them rule consistently, fairly, and in accordance to established legal principles, it is hard to believe that such threats would not place undue psychological burdens upon them. What’s popular is not necessarily right, and the judges have a duty to ensure that their decisions are fair and just, regardless of popular opinion. The attacks are no different from those lodged against Judge Dufton by the pro-Beijing camp in the Ken Tsang case and deserve to be condemned equally.\

Another issue with the baseless claims of authoritarian rule in the city is the way they devalue and distract from the fight against real authoritarian regimes elsewhere. By equating the jailing of the protesters and the removal of racist anti-mainland banners to the active repression of freedoms in places like Turkey and Russia, you tacitly undermine the struggles of those who do not have the privilege to make their opinions heard. That the opposition camps can host a lawful protest on national day and continue to speak freely is a testament to the protection of such rights in Hong Kong.

As the old saying goes, your rights end where mine begin. It is important to remember that our rights to expression are conditional upon us respecting the rights of others, and that consequences should be expected if such boundaries are overstepped. We need to respect our courts and our institutions in order for society to progress and improve as one.