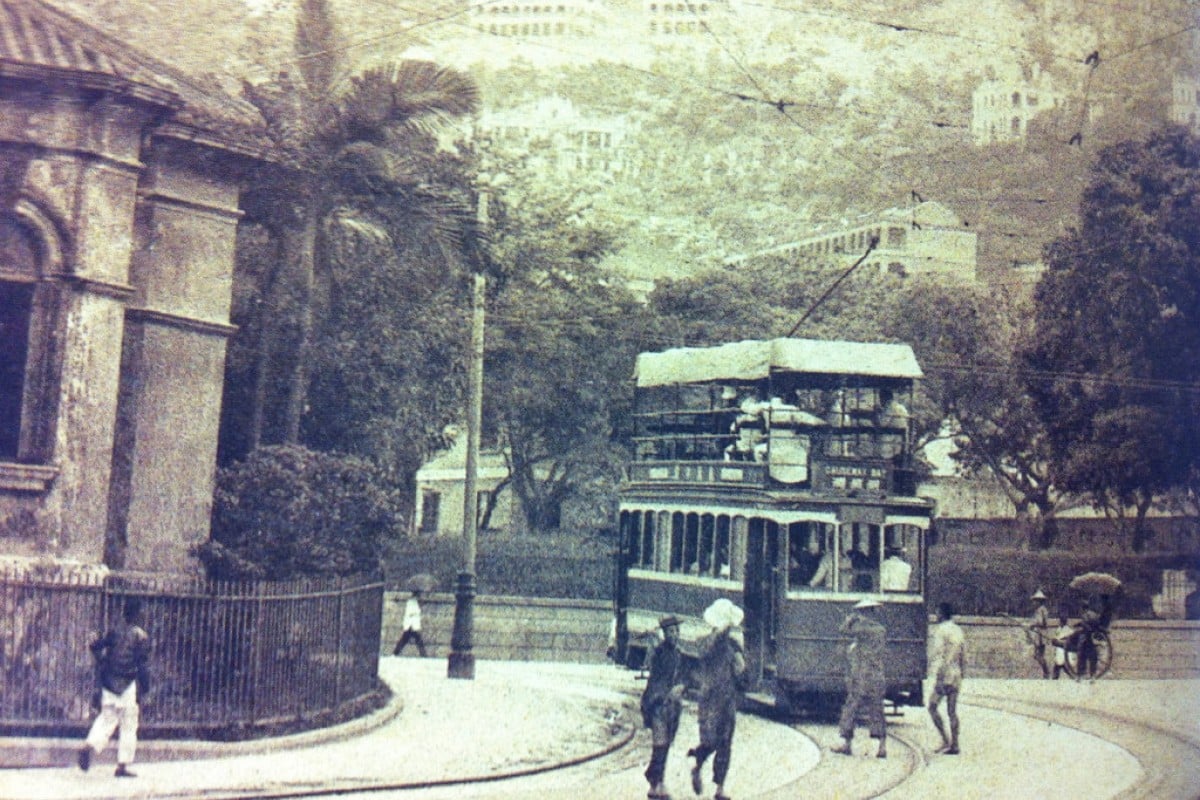

A tram in Admiralty during the 1920s. Back then, Hong Kong was still largely rural.

A tram in Admiralty during the 1920s. Back then, Hong Kong was still largely rural. As loud and dominant as the culture was in the western world back in the Roaring Twenties, Hong Kong was still a remote fishing village, colonised by the British, that was growing quietly in the south of China.

Drawing from two separate memoirs about an expat and a local who were alive in the 1920s, Young Post attempts to bring back some of the long-forgotten memories of Hong Kong a century ago.

In her memoir titled Childhood Memories of 1920s Hong Kong, Barbara Anslow depicts her new life in Hong Kong in 1927, after her entire family arrived on a sailboat from Scotland. She was eight at the time and they moved because her father, an electrical engineer, was to work at the Naval Dockyard.

Hong Kong stories: The Parsi businessman who became a champion of public health

The family lived in several apartments. An upper floor flat on Wanchai Road, then a first-floor flat on Cameron Road in Kowloon. They finally settled on Hong Kong Island on Kennedy Road. They also had an amah named Ah Ng, who lived with them and did all the cooking and housework.

One of the major hurdles for the family was getting used to the hot, humid subtropical weather, among other strange and unfamiliar things like the huge, flying cockroaches and, occasionally, centipedes that measured 10 to 15 centimetres long.

When Anslow was about nine or 10, she attended Central British School on Nathan Road – which later became King George V School – where she was to study French and hygiene.

She says, however, that more interesting than the classes were the games she learned to play with her friends. “Pick up”, which is similar to “rock paper scissors”, was one of them. Another game was called “chucks”, which she described as a version of the traditional Singaporean game “five stones” that involved handmade cloth bags filled with raw rice .

Bathing trips were something she looked forward to during her time in Hong Kong. Organised by the Naval Yard, a small boat would take them to the harbour and anchor near the beach every Tuesday and Thursday after work and school.

“Strong swimmers jumped overboard and swam to the beach; the less able like Mum and us girls, were rowed ashore,” she writes. Anslow and her siblings also took music lessons every Saturday.

The lasting impact of the city's Jewish community

Living on the island seems to have allowed them to socialise more. Back in Kowloon, most of their neighbours were Chinese or Portuguese and mingling with them wasn’t encouraged.

Even as a child, Anslow was aware of troubles in then-Canton – the killings and famine. During the 20s, frequent clashes between warlords took place in the area.

“Mum persuaded me to hand over a prized little doll to Chinese friends of Ah Ng who had told her dreadful tales of hardship in China, in stark comparison with our supremely happy lives,” she writes.

Her easy life in Hong Kong was very different from that of Dou Wan, a blind Chinese local. According to his memoir, The Story of a Virtuoso Blind Musician: Dou Wan (1910-1979), Dou was born in Canton during tumultuous times. In 1925, the teenaged Dou moved to Hong Kong when the Canton-Hong Kong Strike broke out.

Hong Kong's hidden history makers: The Nepalese gurkhas

“Canton was hell to us! We were in a hail of bullets,” Dou says in the memoir.

“Every year we had one or two battles, and battles meant curfews. They never stopped fighting.”

He dreamed about coming to Hong Kong, as everything was cheaper back then, and it was also much easier to earn money here.

As a singer, his job was to sing in tea houses or private parties. He says that there weren’t a lot of singers at the time, but those who were really good at it were called “singing folks”. He adds that everyone at the tea house he worked at was friendly, and that he became good friends with other staff members.

There was another venue where people listened to live music performances known as ba yam gwun, which means “the house of eight sounds”. Opium – a harmful and addictive drug – was sold openly in public in those days, and the musicians performing there were mostly opium smokers, too.

Dou soon became famous in opium dens, and managed to earn a good living from singing. He was able to enjoy some of the privileges of being a singer, such as having someone to fan him when he sang, and being given better snacks than the other staff.

20 things you didn't know about life before the 1997 Handover

Dou had always lived in Mong Kok. In that area, there were lots of ba yam gwun, opium dens, and tenement houses for the common people and blind men.

He says that in old Hong Kong, people didn’t usually dine out. Instead, the people in his area would often share meals or boarding rooms, adding that the working class enjoyed helping each other out. Although they didn’t have a lot of material things, they had each other’s company.

“Many people in the tenement boarded with others ... I boarded with a family,” Dou says.