Preview of the Hong Kong factories turned design hub The Mills as complex nears completion

Three repurposed factories in Tsuen Wan to deliver exhibition space, fashion catwalk shows and co-working opportunities for homespun innovation

When the hoardings come down at The Mills, the four years spent on rejuvenating the cluster of disused cotton mills in Tsuen Wan will not be immediately apparent – and the architects wouldn’t have it any other way. “We didn’t try to change the external look of the buildings at all. It would have been too easy to erase the past. This is all about augmenting the past,” says Ray Zee, head of design at Nan Fung Group’s Hong Kong property division and former assistant professor of architecture at the University of Hong Kong.

Zee was seconded to this unusual project by the upmarket developer in 2014, and recently took Post Magazine on an exclusive tour of the property before its opening later this year.

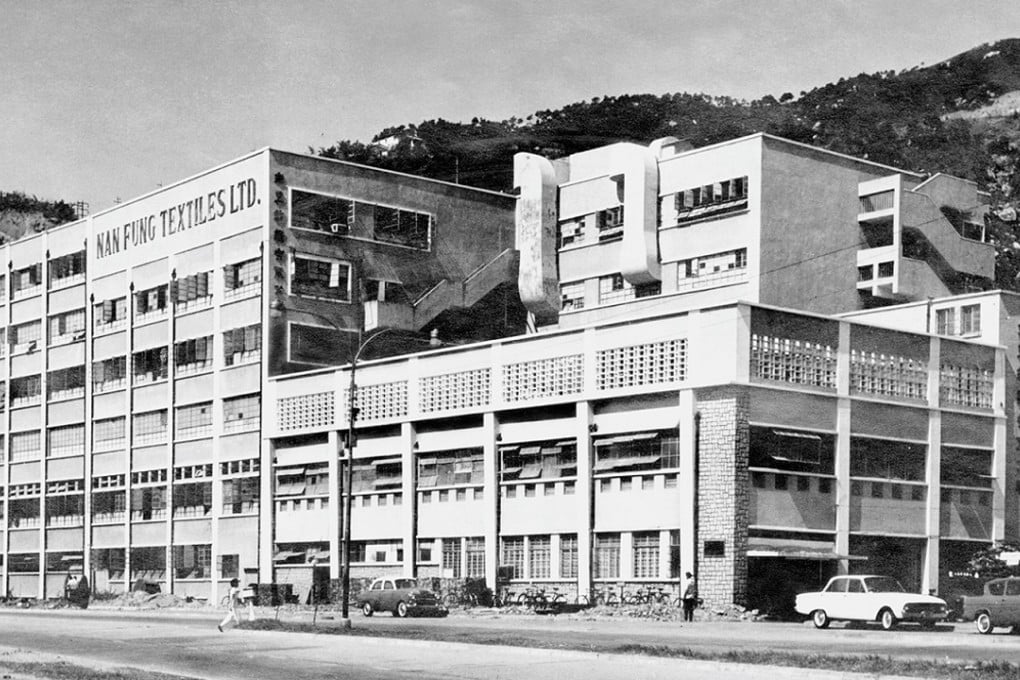

The buildings known as Mill 4, Mill 5 and Mill 6 were built in the 1950s and 60s by Chen Din-hwa, the late founder of Nan Fung. Chen had moved to Hong Kong from Ningbo, in Zhejiang province, when the Communists took power in 1949, and proceeded to build the city’s biggest yarn-spinning business, Nan Fung Textiles, becoming known as the king of cotton yarn. Mills 1, 2 and 3 were knocked down in the 80s, a few years after China’s paramount leader Deng Xiaoping opened up the mainland for outside investment. But, surprisingly, the family business left the three remaining low-rise buildings standing, even though the spinning business closed in the 2000s. Nan Fung had, by this time, become a property developer and the temptation to knock them down and turn the old mills into something far more valuable must have been strong.