Advertisement

Advertisement

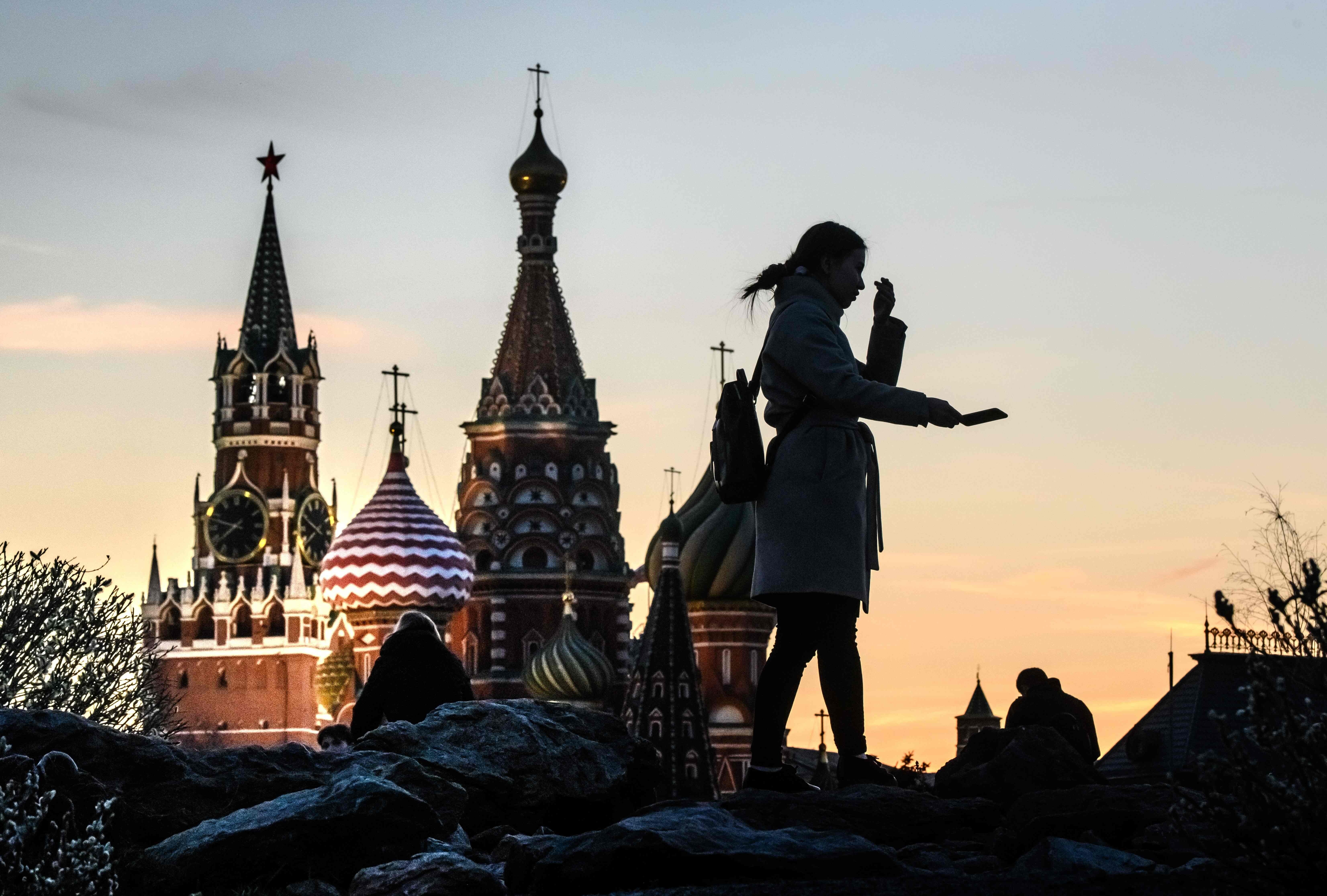

Dmitriy Frolovskiy

Dmitriy Frolovskiy is a political analyst and independent journalist. He is a consultant on policy and strategy, and has written about Russia’s foreign policy.

Dmitriy Frolovskiy is a political analyst and independent journalist. He is a consultant on policy and strategy, and has written about Russia’s foreign policy.

China is searching for alternative sources to Australian iron ore, looking to India, Myanmar, Mongolia and Guinea, among others. Russia could be the answer given its proximity to China, large iron ore reserves and friendly political relations.

At a time when much of the West is planning an exit from fossil fuels, Russia is proceeding with an enormous oil project. One key reason is China, which doesn’t see a swift energy transition as a realistic path and could drive global oil demand in the medium term.

Oil refineries in the US and Europe are flailing while China adds mega facilities, supported by demand for plastic and petrochemicals as Asia recovers more quickly from the pandemic.

While projections suggest the pandemic will not hurt the Russian economy as badly as feared, stagnation and inefficiency continue to hold back its growth. The Kremlin should institute deep structural reforms to boost growth and avoid a worsening deficit.

Advertisement