- Daniel Reid got into Chinese culture after an LSD trip in 1969, and spent the next 50 years in Asia, where he influenced the detox and fasting trends

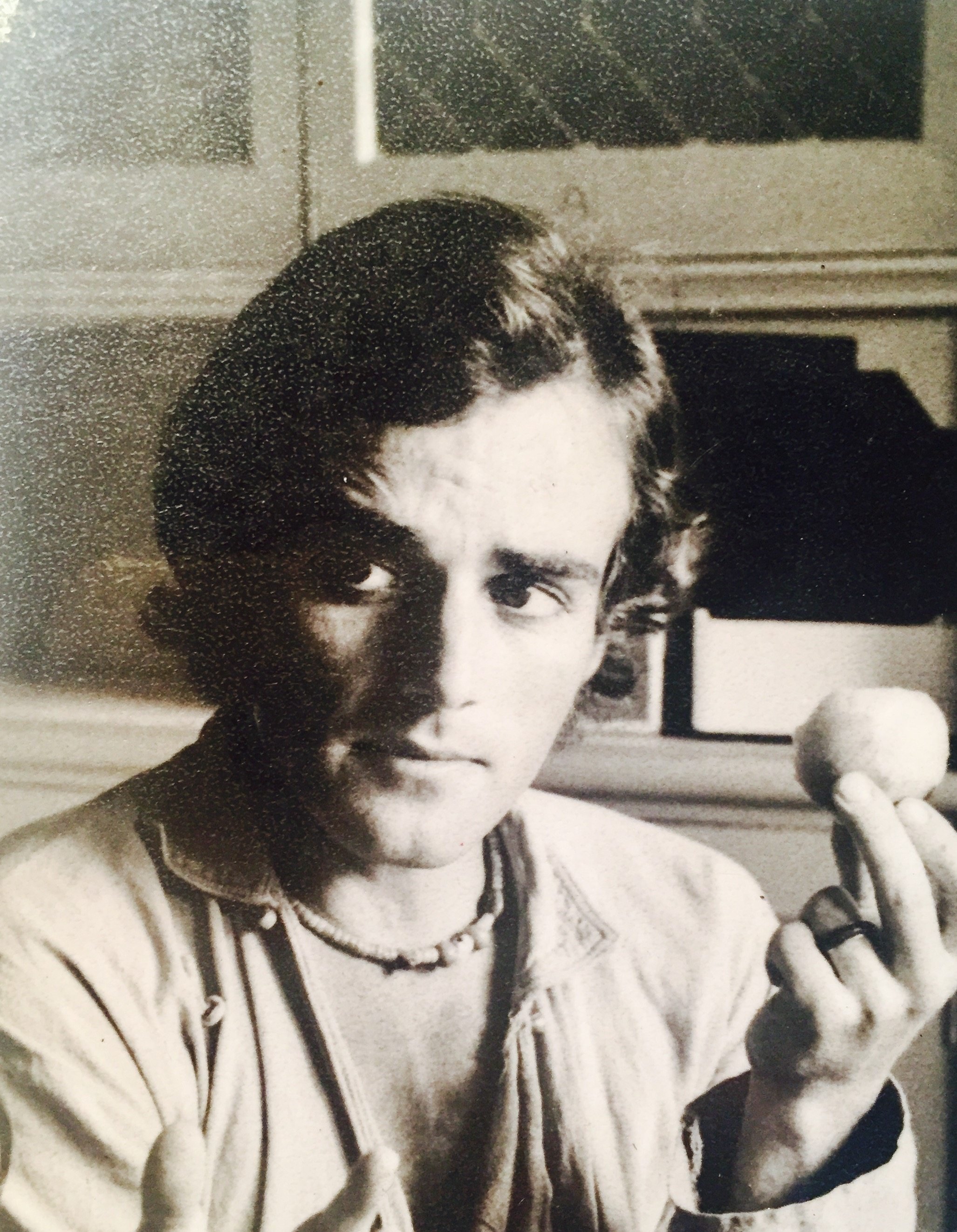

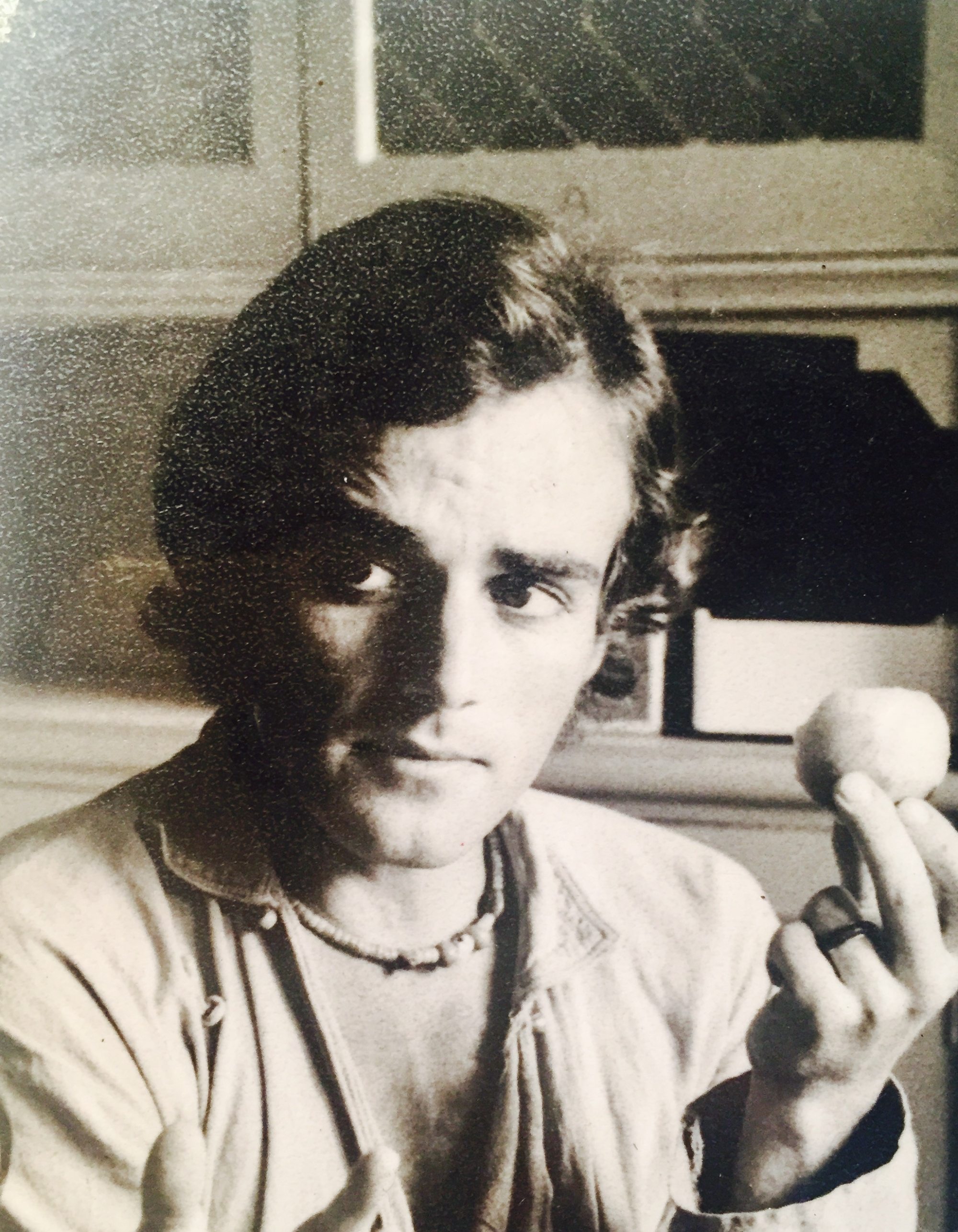

In the autumn of 1969, Daniel Reid was a long-haired, freewheeling undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley, living in “a ramshackle house […] with eight hardcore hippies, none of whom were students”, according to Reid’s 2018 memoir, Shots From the Hip: Sex, Drugs and the Tao.

Reid was in his senior year but still undecided on a major. Then one morning he ingested what he calls a “macro-mega-dose” of LSD and wandered into a lecture on Chinese culture.

“The guy starts talking about China for an hour and a half. And it’s unbelievable! It’s like, I knew all this stuff! I had that feeling that this is so familiar,” Reid tells me, describing this uncanny experience of his American youth, more than half a century later, at a Chinese tea table in his sun-filled living room in Chiang Mai, northern Thailand.

From that psychedelic déjà vu, Reid went on to a career of more than 50 years in Asia, authoring at least 35 books and establishing himself as an expat literary guru on Eastern philosophy, herbal medicine and holistic health.

His greatest influence, however, may have been as an ideologue for a nascent “health and wellness revolution” that began to coalesce in the 1990s around hippie camps on the Gulf of Thailand, where passions for healthful living and spiritual harmony have developed into a giant industry of multimillion-dollar detox resorts.

Reid’s first major book, The Tao of Health, Sex and Longevity, published in 1989, has sold an estimated 350,000 to 400,000 copies and has been translated into eight languages, including Chinese.

They offer self-help for mind, body and spirit – if you’re willing to pay

Read today, the health guide feels a bit strange for its fetishisation of Chinese traditions, including esoteric practices such as “ejaculation without leakage”. But in trying to bridge the Taoist concept of health with Western naturopathy, it proposed some influential ideas, especially a formula for a seven-day fasting cleanse.

Within three years of publication, this cleanse was taken as a blueprint at The Spa, Thailand’s first resort devoted to the fasting cleanse, which opened in 1992 on the island of Koh Samui and set the template for a budding industry.

In the three decades since, “Samui became the detox capital of the world,” says The Spa founder Guy Hopkins.

“Now, there are about 60 fasting centres globally. Of these, 40 are in Thailand, of which 30 are in Koh Samui, Koh Phangan and Phuket,” says Mel Loverh, founder of the Health Oasis Resort, which opened in Koh Samui in 1997, the island’s third centre for fasting cleanses.

Holistic health has become so big that Thai tourism authorities now promote the nation as “The Wellness Capital of Asia” and “the leading country in the world for health and medical tourism”.

The government’s latest five-year tourism development plan projects tourism as accounting for more than a quarter of Thailand’s gross domestic product, with health and wellness expected to draw 4 million visitors a year.

And yet, few of those 4 million will ask: who was this mysterious Daniel Reid, or this cohort of health nuts who laid the foundation for detox to develop into such a massive industry?

Reid and this crew of other wellness pioneers emerged from the cultural radicalism of the ’60s, then found their way to Thailand via party trails, psychedelic experimentation or spiritual practices of kundalini yoga, Japanese Zen, Indian ashrams and vipassana meditation centres.

On a recent trip to Thailand, I met four early pioneers who, like Reid, came straight out of late ’60s San Francisco hippiedom, while others arrived via the Goa party circuit or New Age movements.

Reid’s story is full of excesses and eccentricities, and it would be hard to call him a representational figure of this wellness revolution. (Though his books are still treated as scripture in some spas today, holistic practitioners cite him among a full library of influences.)

His memoir’s title, Shots From the Hip, is not a gunslinger metaphor, nor a brag of verbosity, but a reference to smoking opium “in the traditional Chinese way”.

Reid smoked the drug throughout the 1990s in the last legal opium den in Vientiane, Laos, and, even though he almost died from an overdose, claimed opium gave him “the most sensible approach to earthly existence I’d ever experienced”.

His memoir also includes stories of spirit channelling, past-life experiences and other supernatural forms of karmic reckoning. But at the same time, it holds a wealth of verified detail on people and places that have defined expat networks in Taiwan, Thailand and throughout Asia since the 1970s.

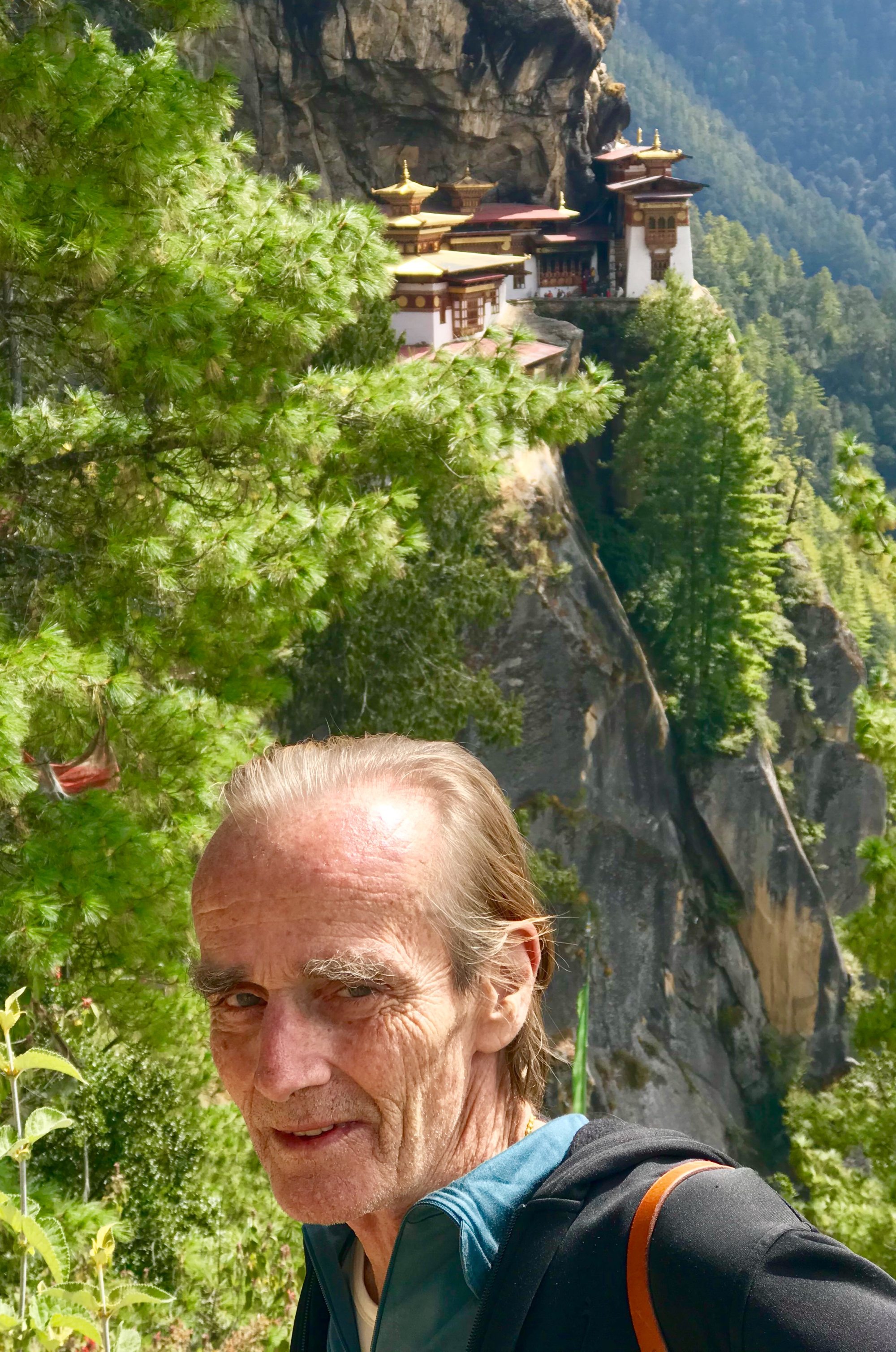

Reid, now 74, says he decided to write the memoir as a way of stepping from behind the curtain of his literary oeuvre after a near-death experience in 2014.

As an author, he says, “people think [you’re] sort of a monkish type of person, or a scholar who never leaves his library […] and that’s not really who I am.”

So he decided to tell his story of Sex, Drugs and the Tao, but notes that, “If my literary agent were still alive, he would’ve said ‘No way’.”

Since the early ’90s, Reid has lived on and off in Chiang Mai. The ancient Thai city of gleaming golden Buddhas, long known for chill vibes and a languid lifestyle, has always been popular with foreign backpackers and local tourists but these days it probably won’t be an to describe it as the Portugal of Southeast Asia.

Owing to the influx of co-working spaces and the digital nomads who inhibit them, the one square mile moated warren of the old town has become a bit of a zoo.

Yet within the moat, one can still find a few quiet streets of elegant old Thai houses with teakwood upper floors, verandas streaming with the crisp sunlight of Thailand’s northern plateau. It is one of these that Reid calls home.

We settle at his tea table, where he has taken time to choose a clay teapot from an arsenal arranged on the wall.

After preparing a pot of Taiwan high-mountain oolong, he pours the first cups and pronounces the Chinese phrase, “pin ming lun dao” – to drink tea and discuss the Tao. And with this, we begin to discuss his life.

Reid was a born expat. His father was a senior vice-president at Trans World Airlines and his early life was spent in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, while Europe was his backyard.

We boarded flights to exotic places most of our American friends had never heard of as casually as they boarded a bus to Los AngelesDaniel Reid on his early journeys

In that era of travel, his father was able to empower him and his brother with “1-A” grade corporate airline passes and blank ticket slips they could fill out on the fly. By his teenage years, he was a seasoned world traveller.

“We boarded flights to exotic places most of our American friends had never heard of as casually as they boarded a bus to Los Angeles,” Reid has written.

In the ’60s, Reid moved with his family to San Francisco, but he continued the life of a low-rent jet-setter. While circling the globe during a two-week college break, he found his way into a brothel in Bombay, now Mumbai, where he had his first experience with opium, “the most unforgettable smell on Earth”.

His life didn’t find direction, however, until that fateful moment in a Berkeley lecture hall, when he blew his mind on the double whammy of Chinese culture and acid. Reid was drawn in by the Chinese poets and classics, which he avidly memorised and would later quote in Taipei bars as a sort of party trick.

By 1971, he was enrolled in a master’s programme in Chinese at the Monterey Institute of International Studies, in California.

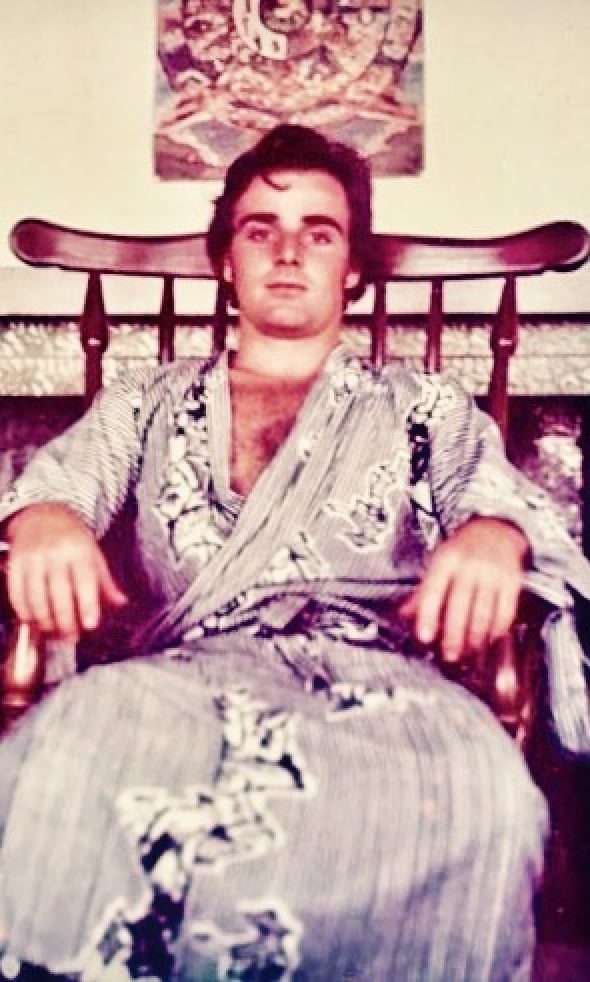

When Reid landed in Taipei, at the age of 25, he wrote in his memoir, quoting Somerset Maugham: “Sometimes a man hits upon a place to which he mysteriously feels he belongs. Here is the home he sought, and he will settle amid scenes that he has never seen before, among men he has never known, as though they were familiar from birth.”

By day, Reid managed an international hotel coffee shop, a major expat hub, and by night he plunged into Taipei’s “floating world” of girlie bars.

“For Western men like me who came to live in Taiwan in the early 1970s, Taipei was a flourishing garden of delight,” Reid writes, describing himself as a “barfly” and “a mad bee [who] understands only the pursuit of fragrance”.

He drank to the point of delirium tremens and estimated that he romped “in the clouds and rain” with more than 1,000 Taiwanese women during his first decade on the island, according to a diary he kept.

The women were bar girls, waitresses in clubs he managed, “stolen romance” with married women – some liaisons he paid for, many he did not. (Years later, he bragged that he cuckolded a Beijing-appointed Tibetan lama by stealing his mistress for a week-long fling in Hong Kong.)

At the same time, Reid began writing to escape the grind of the hospitality game, penning travel pieces for in-flight magazines, then entire guidebooks.

His first break was a Hong Kong commission for the Taipei section in “a sybarite’s guide to the nightlife scene in East Asia”. In 1984, he wrote Taiwan’s first complete English guidebook, Insight Guide to Taiwan.

In 1985, when China suddenly allowed the first travel permits for Tibet after decades of having closed off the territory, a Nepal-based adventure travel agency, Tiger Mountain Travel, needed a Chinese speaker for the first overland tour from Lhasa to the Nepal border, and Reid was enlisted for the job.

After that trek, recalls Reid, “I stopped in Hong Kong to see my editor,” Derek Davies, a legendary figure at the in-flight magazine publisher Emphasis Hong Kong.

“And he said, ‘Oh, by the way, this agent came in. He’s an Englishman, used to work for The Guardian and lives in New York now. He’s looking for non-fiction book titles on China’.”

That agent was Robert Ducas, a publishing world heavyweight who would later handle Henry Kissinger’s memoirs and was once described by The Washington Post as “a tall rumpled Englishman who looks like a character out of an Evelyn Waugh novel”.

Reid explains, sipping oolong, “At that time, there was basically nothing current in print about China. The entire country had been closed off for decades, so he was maybe sensing that there was a void and a big market for it.”

So he pitched “a book in which traditional Chinese healthcare was explained in a clear way and related to science”.

As Reid tells the story, Ducas replied, “Great, you write it and I’ll sell it.”

Reid’s manuscript was eventually published by Simon & Schuster in London and New York as The Tao of Health, Sex and Longevity. It sold well, and quickly.

With that book, “I sort of got up into the major leagues,” says Reid. “And as long as I kept the quality up and the same topic, Chinese medicine, I sold [Simon & Schuster] every one of the books that I proposed.”

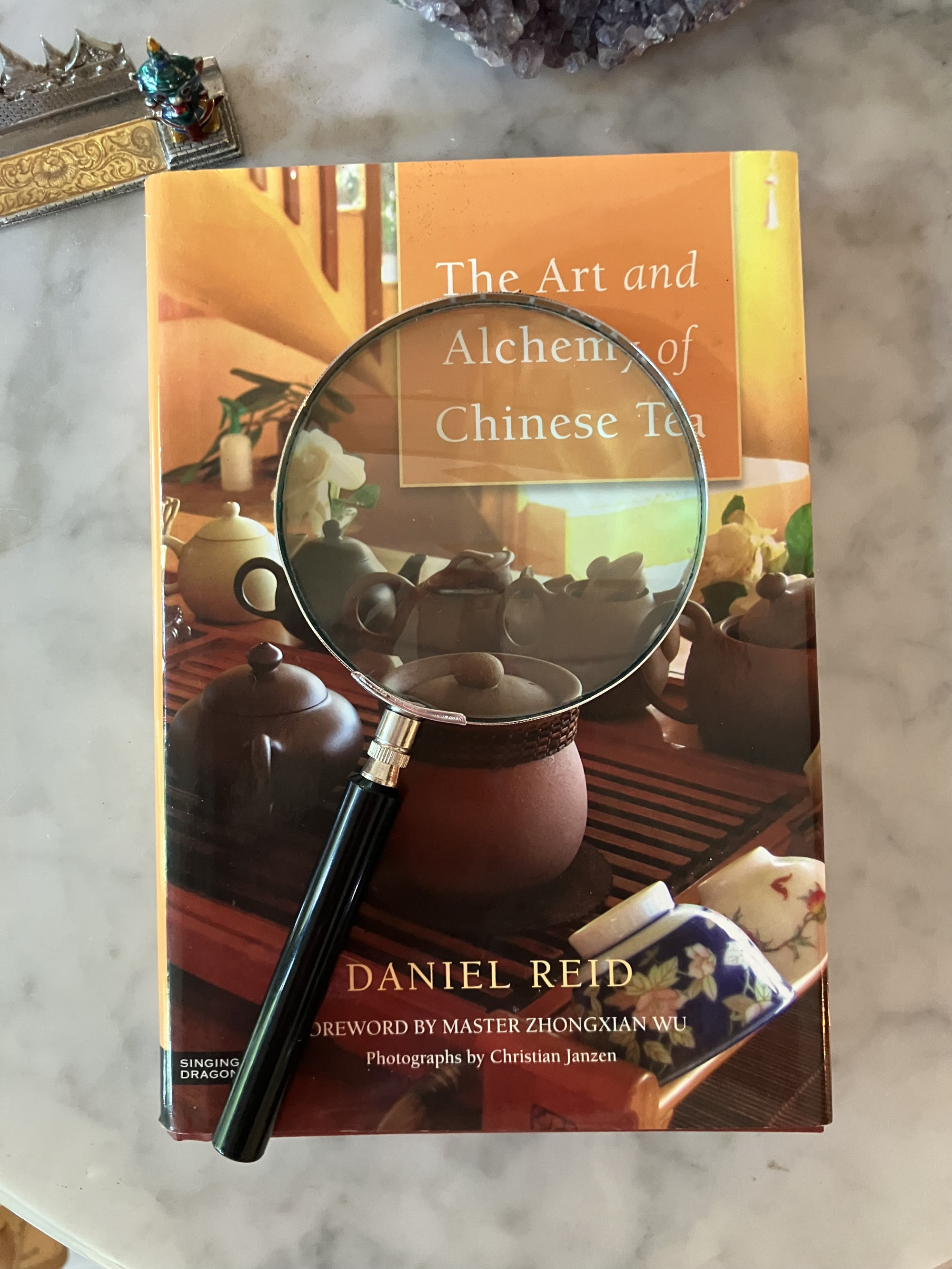

(Later titles included The Complete Book of Chinese Health & Healing: Guarding the Three Treasures [1994], A Handbook of Chinese Healing Herbs [1995] and Chi-Gung [1998]. At the same time, Reid used niche publishers to release non-fiction titles on tea, opium and other Chinese traditions.)

But just as Reid’s career as an author was taking off, his visa status in Taiwan took an awkward turn. His Insight Guide had given the head of Taiwan’s Tourism Bureau justification to grant him a special, no-strings “consultant visa”. But after the bureau’s director retired, Reid’s visa was cancelled.

Ever the journeyman and sensing new opportunities in Thailand, he moved to Bangkok in 1989. Not long afterwards, he was approached out of the blue by a fellow Californian, who wanted to talk to him about opening a spa.

As recently as the 1980s, Koh Samui, the second largest of Thailand’s 1,430 islands, was still a virgin paradise of white sandy beaches overhung with coconut palms, where visitors stayed in primitive bamboo huts.

Now, depending on who you ask, it is the ne plus ultra in luxury spas, a Mecca of healing and wellness, a party island of go-go bars and boozing Western tourists, or for the more dedicated, a Hotel California of retirement.

The island’s transformation began in 1985, when the Tourism Authority of Thailand launched the Master Plan for Tourism Development of Koh Samui, opening Samui International Airport in 1989, and completing the island’s 50km ring road not long after.

The official goal was to pave the way for value-added, luxury resorts.

Hopkins, The Spa founder, didn’t hear about the island until 1990. A San Francisco-born entrepreneur with a career in fashion retail and restaurants, his life underwent a sea change after he nursed his mother through the final stages of a painful death to cancer in the ’80s, just as he was hitting middle age.

Following that trauma, Hopkins ditched his United States businesses to study up on new health trends while living in the Thai beach resort of Pattaya, itself built for a certain US soldier’s R&R-style custom during the Vietnam war.

What Samui was then – you couldn’t recognise it today. The villages were just villages. It was all dirt roads and the main method of transport was by boatThe Spa founder Guy Hopkins on Koh Samui in the early 1990s

While there, a friend approached him about opening a “health resort” on a relatively undeveloped island in the Gulf of Thailand – Samui.

“I said, ‘Where?’ I had never even heard of the place,” recalls Hopkins, now 82 and speaking by phone from his home outside Chiang Mai. “But when [my friend] said ‘health resort’, I said, ‘Count me in.’

“What Samui was then – you couldn’t recognise it today. The villages were just villages. It was all dirt roads and the main method of transport was by boat. There were a few hippies there doing yoga and things. They had built a kind of tepee and used it as a steam room.

“Samui was a discovery. I guess you could say people had found it, but it was really just in the process of being found.”

In Bangkok, Hopkins had read Reid’s famous book, short-handed by popularity to The Tao of Sex. “It was in the big bookstores in Sukhumvit, which featured it very prominently. I read it and was impressed. And then I found out that Dan was living in Bangkok, so we met and had dinner.”

Hopkins also tried the book’s formula for a seven-day fasting cleanse, and was wowed by the results.

“Guy [Hopkins] got his whole idea for The Spa from my book,” Reid tells me. “It was specifically set up to do the seven-day fast with colonic irrigation. That’s what Guy wanted to do, and so he approached me.

“I said, ‘Fine. You know, I write for people to learn something, but if you want to make a spa that features this programme, please, be my guest.’ I mean, I think he was thinking I might want something. But I said, ‘No, it’s not necessary.’ And so Guy started it, and then after a while, everybody copied him.”

Reid “had a great deal to do with it”, acknowledges Hopkins. “He needs to be recognised as having a great impact on the health and wellness scene.”

The Spa opened on Samui in 1992 as a small camp of seven bungalows set around a 70-year-old building Hopkins used as a reception centre. The camp was located on an otherwise empty stretch of the postcard perfect Lamai Beach. (Though Lamai Beach is still heavenly today, The Spa’s beach complex is now on a traffic-snarled highway of resorts and strip malls.)

During its construction, Hopkins befriended Ajahn Poh, Buddhist abbot of Wat Suan Mokkh on the Thai mainland, who had grown up nearby and proved a useful bridge to the local community. (In 2004, Poh opened the Dipabhavan Meditation Centre just up the mountain from The Spa, specialising in leading Westerners through what Hopkins calls “fasting for the mind”, 10-day vipassana meditation retreats).

Though The Spa was the first in a wave of fasting cleanse centres that appeared in Thailand and later around Asia, others sprang up on Samui and nearby Koh Phangan.

Hillary Hitt, a Jewish woman from Chicago who had studied kundalini yoga in San Francisco in the 1960s, established Dharma Healing International on Samui in 1994.

On Koh Phangan, a British couple who had bounced along a trail of parties and ashrams from Goa to the Gulf of Thailand, Gillian Beddows and Steve Sanders, have been running a secluded resort called The Sanctuary since 1990.

Today, a seven-day detox cleanse on Samui will cost between US$1,200 and US$5,000 and, beyond the dedicated fasting resorts, nearly every top international resort offers some sort of detox.

Even at the Four Seasons, where villas start from around US$2,500 a night, you can get an “immunity-boosting coconut and magnesium massage”, for US$220.

What the whole thing has become is “simply unbelievable!” exclaims Hopkins. “In the beginning, we rented bungalows for 300 baht a night,” which was around US$5 in 1993. “And the health treatments were very affordable. Now that’s all completely changed.”

By the 2000s, “the five-star hotels were sending spies to our place, which was three-star at best, or maybe two-star”, recalls Health Oasis founder Loverh. “They wanted to see what was going on and how these weird things were attracting all these people.”

Around 2003 or 2004, detox became a buzzword, then a label more broadly applied. This word has been abused and hijacked by many programmesMel Loverh, Health Oasis founder

Thus commenced the health and wellness revolution, says Loverh. Samui and Phangan “had instrumental roles in shaping the spa industry in Thailand and globally. There were other pockets around the world, but it took years to catch on, while in Samui it was already all happening.”

Western media also discovered Samui and The Spa. By 2012, Fox News had named The Spa one of the top 10 detox resorts in the world and Restaurant magazine listed it as one of the world’s top 50 dining experiences. US and British reality shows filmed at The Spa in 2003 and 2004.

“In the beginning, no one labelled these spa treatments as ‘detox’,” says Loverh. “We simply said ‘healing’ or ‘fasting’. But then around 2003 or 2004, detox became a buzzword, then a label more broadly applied. This word has been abused and hijacked by many programmes.

“With most of those the focus became pampering, not detox. The five-star resorts did it because people were asking for more holistic treatments, but most of them were just copycatting bits and pieces. It was very superficial.”

For Reid and Samui’s old guard, the basic protocol for a cleansing fast is to deny solid food on one end and on the other to remove waste via colonic irrigation, or colonics, a type of turbocharged enema that pushes water through the colon in a continuous flow.

Fasters consume liquids, such as coconut water or vegetable broth, as well as vitamins, minerals and herbs. Regimens run from three to 14 days, with a sweet spot frequently claimed at seven days.

Japan’s ‘sushi terrorism’ forces conveyor belt restaurants to rethink

Reid calls his detox programme “Renew Your Lease on Life” while Hopkins named The Spa’s “You Changed My Life”. They believe that fasts allow the body to remove toxins, reboot the immune system and heal itself through “divine immune intelligence”.

In mainstream medicine, however, the fasting cleanse is controversial. Few doctors will recommend fasting, and most will say it’s dangerous for those with diabetes, heart disease or other conditions.

Though old-guard fasting centres remain an expat-led cottage industry – resort capacities range from 20 to 60 guests – they have guided tens of thousands.

The Spa, Health Oasis and The Sanctuary estimate they have conducted more than 20,000 fasting cleanses each since the 1990s, while Hitt estimates she has guided as many as 7,000 fasts.

Most fasters are aged 30 to 60, and there are slightly more women than men. At least a quarter of visitors are repeat customers. The vast majority are Western. Only one in a 100 is Thai.

Frequently, it is the idea of weight loss that draws people in, while others seek to combat chronic illness. Most simply desire to feel more energetic or refreshed.

“No one has ever died. No one has ever hurt themselves fasting,” says The Sanctuary’s Beddows.

“We never had to call an ambulance for anyone.”

In early 1992, after Reid had spent a little over two years in Bangkok, he was 44 and had finally had his fill of “sexcapades”. He relocated 700km (435 miles) north to Chiang Mai, then still a relatively sedate but intellectual city, “to live the reclusive life of a scholar and writer”.

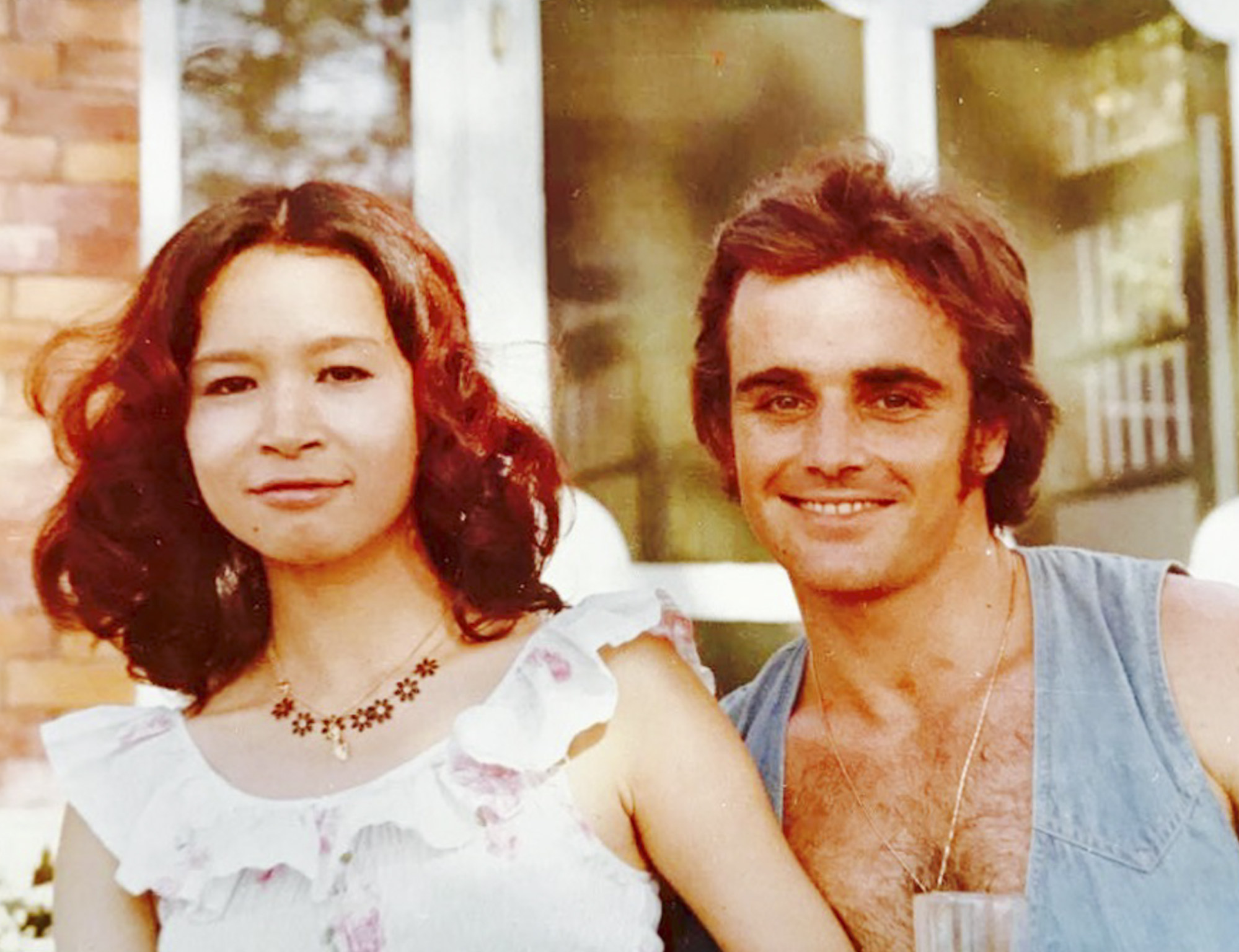

That same year, he was joined by a Taiwanese girlfriend, Snow Chou, who has been his partner – both in life and guiding private detox cleanses – ever since. In his memoir, this latter phase is given the header, “Energy, Light, and Luminous Space”.

For all these health pioneers, these are the autumn years. On Koh Phangan, Beddows recalls helping with the first of the legendary full-moon parties of the ’80s, saying, “I was into all the raving and drugs and whatever,” but by the ’90s, her “search for clarity […] sort of strayed away from drugs – which drugs gave in their own way – but we were after a different clarity, and the fasting brought that to the table.”

If there is a common thread running from ’60s hippiedom to Thailand’s current enclave of health and wellness, Reid says, “it’s basically an orientation towards society. You know, I was there lobbing tear gas canisters back at the police in the Berkeley riots. I went to the Cambodia protest in Washington DC”.

For him and others, disillusionment with politics led to life as an expatriate, and distrust of mainstream medicine to holistic healing. But even as the detox industry is booming, the outlook for the fasting cleanse is changing.

“The number of resorts is not mushrooming as it once was,” says Loverh, who believes the cleanse trend has hit a plateau.

Between 2012 and 2014, Hopkins sold The Spa for a small fortune, retiring into his new role as a health coach.

His Samui holdings were bought by a Thai-owned hotel consortium, the Richmond Group, which renovated the property into a four-star luxury resort with more diverse detox offerings. About half The Spa’s guests still come for fasting cleanses.

Such resort owners foresee future trends that focus on luxury, anti-ageing treatments supported by new medical technologies, and even psychedelic-based therapies, such as psilocybin mushrooms, should they become legal in Thailand. How’s that for full circle?

Ain’t no mountain high enough, not even Everest, for these Nepali villagers

Thai tourism authorities, meanwhile, now boast of medical clinics offering integrative cancer care, regenerative medicine and even medical cannabis (which was legalised in Thailand in 2018).

They have also declared improving safety and hygiene standards as a key goal in the latest tourism plan, though it is still unclear whether this will lead to regulation of fasting and detox.

In Chiang Mai, Reid and Chou have noticed a growing Chinese clientele, who often come from polluted cities and are desperate to detox. A circle within a circle.

Sipping his tea, Reid reflects that a major reason for telling his story of sex, drugs and the Tao was to let people know, “You don’t have to be a monk in a temple to understand these things and to practise them.”

“You know,” he says, “how many people would start a whole lifetime career based on an LSD trip?”