One woman’s Hong Kong ovarian cancer journey and her positive message for fellow sufferers, their friends and family

Hilary Faulkner, diagnosed three years ago with an aggressive form of cancer that has since spread through her body, has captured her positive approach to the disease in a book to help fellow ‘cancer virgins’

Hilary Faulkner is sitting on a bed in a small room, in the Hong Kong Integrated Oncology Centre, smiling and laughing as she recounts her ongoing battle with ovarian cancer.

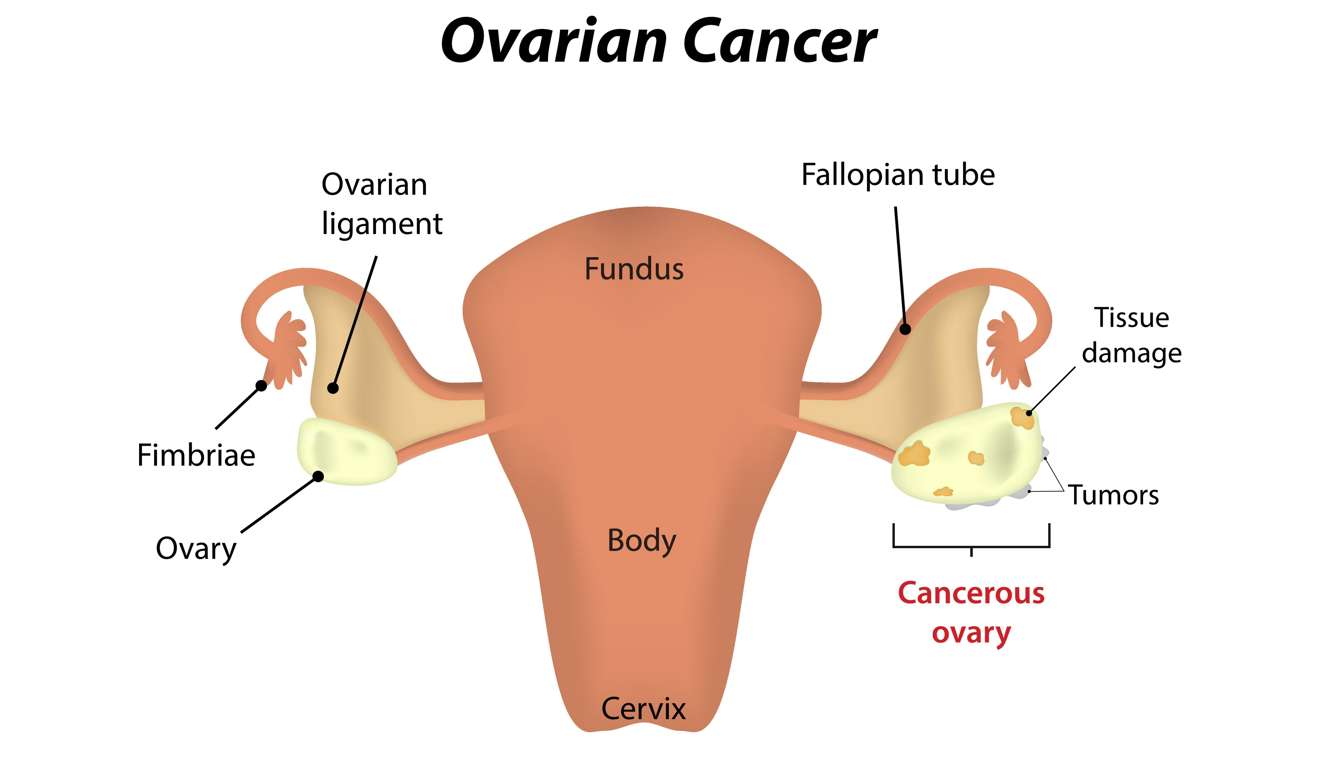

March is Ovarian Cancer Awareness month in Faulkner’s native Britain, and she praises the support she has received in Hong Kong, where it is the sixth most common cancer among women. “The chemotherapy nurses are the unsung heroes because they’re the ones that put the needles in, monitor you, phone you the next day to see if you’re doing OK, and really give you a lot of support.”

Faulkner is on a mission to raise awareness of ovarian cancer, a disease she was diagnosed with in 2014, using her own journey to shed light on a medical process only the initiated have been unfortunate enough to experience.

Writing on her “secret blog”, she shares her experiences with those new to the treatments and provides space for others to do the same. The posts can be seen only by those she has vetted, and include insights on lengthy chemotherapy treatments, what to expect from a positron emission tomography (PET) scan, which drugs she has taken, the side effects of treatment, gene sequencing, and other basics of undergoing treatment.

Keeping cancer on the run: Hongkonger fights disease on city’s trails

“You’re just like a cancer virgin when you start,” she says. “You have no idea that there are so many cancers, so many drugs to treat cancer, how it affects your blood, just how much time it takes up really. You just kind of start on this journey and you don’t have a clue.”

To understand Faulkner’s motivation to share stories it is important to understand her “cancer journey” as she refers to it. It all began in April 2014.

“I just happened to be going to work one day. I had a little bit of bloating, a little bit of backache, which you kind of get when you’re over 50 anyway. I didn’t really think anything of it. Then when I was walking, I just felt something go ‘pop’.”

Hong Kong’s 15,000 cases of breast cancer complication made worse by lack of awareness

Faulkner had previously been diagnosed with endometriosis – a condition in which tissue that normally grows inside the uterus grows outside of it, resulting in pelvic pain – and was attuned to shifts in her body.

Her mind was momentarily put at ease when her doctor agreed it might be a burst ovarian cyst, something she felt was not uncommon for women over 50. She was advised to go home, rest, and see if the pain went away, which it didn’t. An ultrasound showed a mass on her left ovary and she was again told it was most likely just a burst cyst. A second opinion suggested that ovarian cancer could not be ruled out.

Faulkner underwent a CA 125 test, a blood test used to detect early signs of ovarian cancer. The results showed no sign of cancer and have since left the now more informed Faulkner sceptical of the test’s reliability.

A co-worker suggested she visit another doctor, who would later become her primary surgeon. They agreed that to be certain the mass should be removed and tested. The surgery, Faulkner was told, would be quick, “in and out”, with a 30-minute wait for test results. When she woke up four hours later she knew the news she was about to receive would not be good.

“He came in and said, ‘I’m really sorry, it’s cancer,’” says Faulkner.

Faulkner was diagnosed with a rare, aggressive form of endometrioid ovarian carcinoma, with a high recurrence rate. She was scheduled for chemotherapy to catch it before it spread.

Faulkner’s next few years would be a whirlwind of chemotherapy and tests, beginning with six cycles of chemotherapy, one every three weeks. She initially lost her hair and the feeling in her fingers. The treatment caused deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) in her left leg, a common side effect that required seven days in hospital.

A scan in February 2015 identified a small, benign tumour near her peritoneum, the thin layer of tissue lining the abdominal cavity. In May 2015 another scan showed the tumour had turned malignant.

“For me the worst thing about having this is the lack of control of your body,” says Faulkner, sounding slightly irritated rather than angry.

Does traditional Chinese medicine have a role in helping patients fight cancer?

In October 2015, doctors decided to go in and take a look. Faulkner was told the cancer had not spread but unfortunately the DVT was in her right leg and together with a pulmonary embolism required a blood thinner for the rest of her life. In November 2015 another operation removed small malignant tumours.

Faulkner next underwent radiotherapy in early 2016. The schedule was gruelling, requiring Faulkner to go in every day. Then, in May 2016, Faulkner went to see her oncologist for what she considered a simple follow-up. “When I walked in I saw stuck up on the screen a huge tumour in my liver,” Faulkner recalled. “I actually had seven tumours in my liver so it had spread.”

After more chemotherapy, Faulkner was hesitant to continue the course of treatment. So she decided to start seeing doctors at the Hong Kong Integrated Oncology Centre, a private cancer centre in Central. They suggested a drug with promising results against clear-cell carcinoma. The drawback was that it would take three months to kick in, so Faulkner decided to move ahead with chemotherapy to shrink the tumours on her liver and “buy me more time”.

I’m a very positive person. I keep on going. But when you get the results of the scan and it slaps you flat, you’re like, oh my God, you know, this might actually kill me

Faulkner’s mother suggested a liver transplant and her doctor contacted a liver surgeon to remove the larger tumours and perform radiofrequency ablation, a technique where heat is used to kill cancer cells, which Faulkner likens to frying the smaller tumours.

The surgery and subsequent ablation saw the removal of Faulkner’s gall bladder and the left side of her liver.

In September, a shadow appeared on Faulkner’s liver requiring another ablation, which was performed with Faulkner awake and watching the progress on a screen.

So far Faulkner considers herself fortunate, having private insurance through her workplace that covered the necessary procedures and employers who allow her to work from home full-time.

But even her insurance has limitations. When she and her doctors decided to forgo chemotherapy and pursue immunotherapy treatment, the option was deemed experimental within her coverage. Her friends and family rallied, raising awareness and funds through various events and personal challenges.

The new treatment made Faulkner feel strong when she was experiencing what she calls “scan-xiety” ahead of her last scan, on December 31.

Faulkner was told tumours had spread to her lungs, lymph nodes, and hip bone, and unfortunately some of the ones they had ablated in the liver had come back.

Even as she details the spreading cancer, Faulkner remains upbeat. Her next scan is this month and she is optimistic, since her new course of treatment involves identifying the genetic sequencing of tumours to prescribe specific, targeted drugs.

“I’m a very positive person. I keep on going. But when you get the results of the scan and it slaps you flat. You’re like, oh my God, you know, this might actually kill me. I don’t know how long I’ve got,” she says. “And the next day I think it through and I go well, OK, that’s what it is, let’s get on and deal with it.”

Faulkner has decided to encapsulate her positivity in a book, her mother’s idea, to help cancer patients better understand treatments and face any challenging situations with a smile.

She started writing Fuk Yu, A Sweet and Sour Cancer Journey Hong Kong Style three months ago while sitting in waiting rooms and between treatments. She hopes to find a publisher willing to share her type of story.

“My goal is to try to get women to look where they have mild symptoms [such as loss of appetite, frequent urination or consistent bloating], question them and go get them checked out. We say ovarian cancer is whispering. Listen to it.”

Faulkner also has advice for people who know someone suffering from cancer. “Just be there for that person. Don’t shy away. I’ve lost quite a few friends who couldn’t cope, which is very upsetting. They just couldn’t face the fact that I have cancer and yet some of my new friends don’t care.”

As she finishes her story, Faulkner remembers a card she received. “It said: ‘Life’s not about waiting for the storm to pass, it’s about learning how to dance in the rain.’ That’s what I do. I dance every day.”