How tofu made it to America, was disparaged for decades but went mainstream when 1960s counterculture exploded

- Founding father Benjamin Franklin was fascinated with soybeans, and Asian immigrants ate tofu in the 1800s while working on the railways and after the gold rush

- In the 1960s the US soybean industry’s growth and the rise of the counterculture ignited interest in vegetarianism, and today tofu is common in US supermarkets

Nestled among street stalls in Hong Kong’s working-class Sham Shui Po district is one of the city’s oldest tofu makers.

It’s 1am and staff at Kung Wo Tofu Factory are busy at work using a stone mill to grind pre-soaked soybeans. The process of making tofu is laborious: the ground mixture is boiled, then strained, before it is pressed into cubes fresh for the morning’s customers.

“We make around 5,000 pieces of tofu every day. We don’t want to add any preservatives to our product; we prefer to make it fresh,” says Kung Wo director Renee So.

The company has been making tofu in Hong Kong for almost 130 years. A narrow alleyway separates the factory into two shopfronts. On the left, customers buy the fresh tofu products – from cubes of freshly made tofu and dried tofu puffs to yuba, or tofu skin. On the right, customers can grab a bite to eat, ordering dishes such as pan-fried tofu with fish paste, deep-fried tofu and even tofu ice cream.

“Tofu is very special because you can prepare it like us in a fast, local street-food way, but you can also put it on a [high-end restaurant] menu for a very high price. Tofu itself is very flexible, it depends how the chef wants to present it to the customer,” So says.

Tofu is deeply ingrained in the culinary landscape of Hong Kong and mainland China. Unlike in the West, it is not usually considered as a meat substitute, but rather just another great source of protein.

The hidden history of xiaolongbao, Shanghai’s famous soup dumplings

The history of tofu goes back over 2,000 years. There are many theories about how it was invented, but the most popular legend has it that a cook in China made it accidentally by curdling soybean soup with unrefined sea salt. According to the US-based SoyInfo Center, the earliest written mention of tofu was just before the Sung dynasty in China in 960AD.

If, then, tofu has been around for centuries in Asian countries, including Japan, Korea, Indonesia and Thailand, how did it make its way to the United States? According to the history books, it’s only in the last 150 years that it has been found in the US.

The first American to document tofu was none other than founding father Benjamin Franklin, who wrote to a friend – and even sent him some soybeans – after reading about tofu in a book while in London in the 1760s.

“Franklin read about tofu in a book by a man named Father Domingo Fernandez Navarrete, who was a Dominican friar and missionary to China,” says Bill Shurtleff, founder of the SoyInfo Center and a guiding figure in the American tofu movement.

“Fernandez Navarrete stated that this is a cheese that the Chinese make from Chinese ‘caravances’, which were actually soybeans. And there are many that would leave ‘poulets’ for it, meaning who would rather have tofu than chicken.”

Despite Franklin’s fascination with tofu, it wasn’t until a century later, in the late 1800s, that it began to be made on American soil, thanks to the arrival of Chinese and Japanese immigrants.

“It arrived with Asian immigrants, conceivably as far back as the 1860s, when there was a large number of Chinese immigrants coming to work on the railways, and in the wake of the gold rush,” says Matthew Roth, author of Magic Bean: The Rise of Soy in America.

America’s first official tofu company – Wo Sing & Co – opened its doors in 1878 in San Francisco, selling fresh and fermented products.

“I have no doubt that the Chinese were making tofu everywhere that they lived, but they kept no records of it,” Shurtleff explains. “The Japanese fortunately kept records, which started in about 1901. They made tofu everywhere that they lived. Even in little tiny towns, there would always be a tofu shop.”

Though it was widely eaten in Asian-American communities, it struggled to break into the mainstream.

“There was this long history of American disparagement of tofu as being just generally weird,” says Roth. “These rectangles of tofu were often dyed yellow with turmeric. They would be piled high in windows in Chinatowns, and Western observers would look askance and wonder what the heck that stuff was.”

One person tried – and famously failed – to change that. In the early 1900s doctor Yamei Kin set out on a mission to show the West that tofu was a nutritious alternative to meat and “a lot less wasteful” than Western meat consumption. Her biggest hurdle was American taste buds.

“Americans do not know how to use the soybean. It must be made attractive or they will not take to it. It must taste good. That can be done,” Kin said in a 1917 New York Times article titled “Woman off to China as Government Agent to Study Soy Bean”.

Born in China in 1864, Kin was orphaned when her parents died in an epidemic. She was adopted by American missionaries and raised in Japan, China and America. She became the first female Chinese graduate of an American medical school, according to Roth.

The charismatic doctor went on to become a Western advocate for the “Chinese art of living”, which included how people in the East ate tofu. Roth says she was a regular on the women’s club lecture circuit, promoting tofu to high society.

“Come World War One she was commissioned by the American government to travel to China to investigate tofu manufacturing and other soy products as possible substitutes for meat during the war, which were rationed and increasingly scarce,” Roth says.

Upon her return to the US, she did not write a report on soybeans as expected, but set up a lab and test kitchen at what is now the Food and Drug Administration to develop different recipes for tofu that would appeal to Western tastes. Despite her best efforts and media interest, Roth says her mission to convert Americans into tofu lovers was “too little too soon” and it all but failed.

“It stands as one of the kind of noble failures in the efforts to promote tofu in the West and among Americans in particular,” Roth says.

Over the course of the 20th century, and particularly since the 1960s and 1970s, tofu went from being a very niche product mainly in Asian-American communities to becoming a widespread American food

Tofu production faced a setback during World War Two. After the attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941, about 120,000 ethnic Japanese living in America were sent to internment camps on the west coast.

Roth says the interned Japanese Americans found the food provided in the camps inedible, so they fought to be allowed to make tofu for themselves. The government eventually acceded to their request, allowing tofu to be made in “all of the 10 internment camps” in California.

In the post-war years, small-scale tofu production continued. Then, seemingly in the late 1960s, tofu exploded into the American mainstream.

The 1960s marked a “perfect storm” for tofu in America, Shurtleff says. The US soybean industry was booming, while the rise of the counterculture ignited an interest in vegetarianism; as a result “tofu started to catch on very rapidly”.

“In the late ’60s, the hippy movement, especially that which was based in San Francisco, sparked a real widespread interest in vegetarianism,” explains Roth.

“It helped spark a greater interest in Asian foods and Asian culture more generally. The anti-war movement, sense of solidarity with the Vietnamese, that was part of it, but also this real interest in Asian spirituality.”

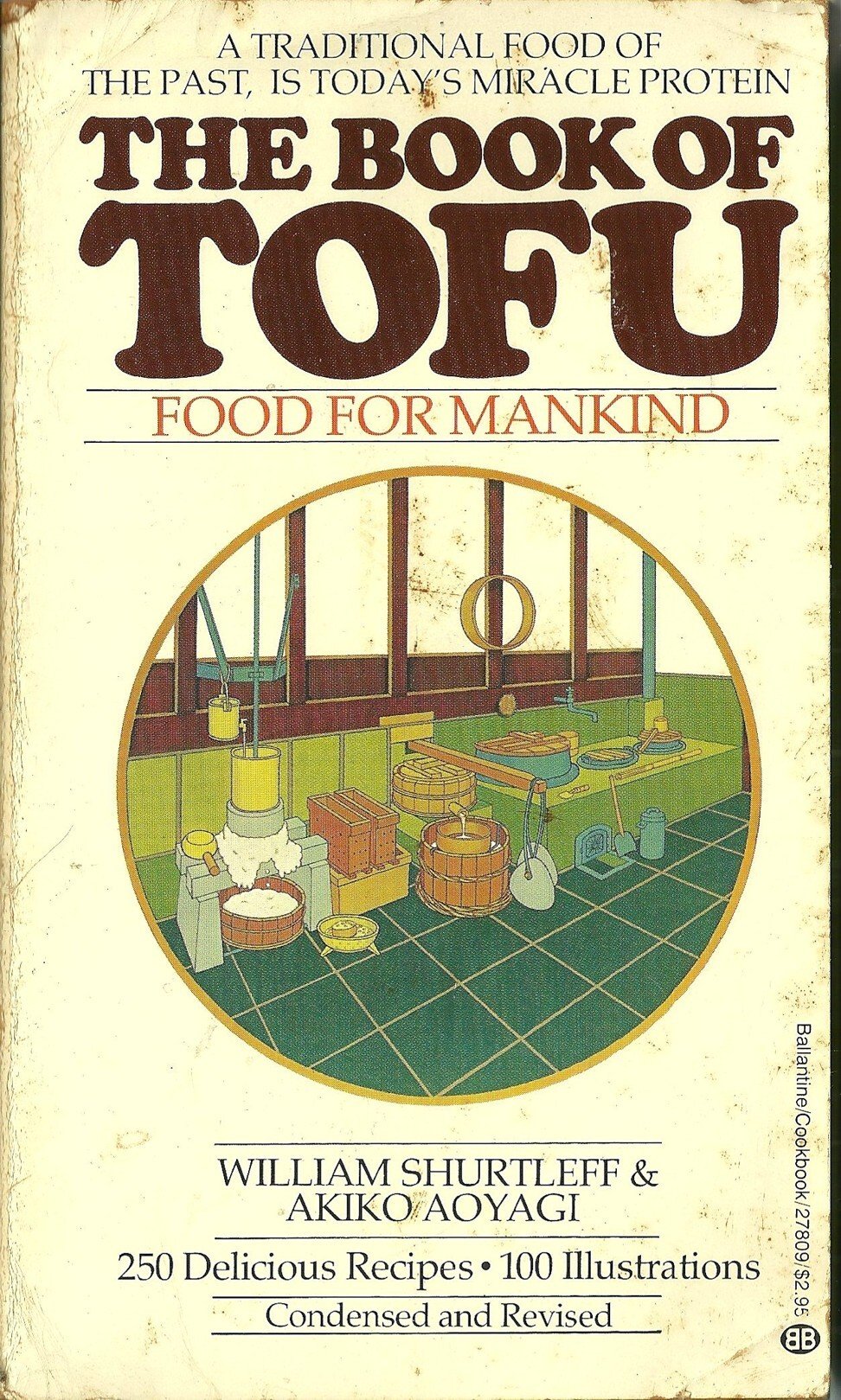

This movement was boosted by the publication of The Book of Tofu, written by Shurtleff and his wife Akiko Aoyagi. The book contained everything from recipes to tofu production details, and was credited with helping to kick-start the tofu revolution in the West, selling more than 600,000 copies.

“I lived in a Zen monastery named Tassajara, in California, and our Zen master was Japanese. And he loved tofu and so we got into the habit of serving tofu. And pretty much everybody grew to like it,” Shurtleff recalls.

“I didn’t really think about it until I got to Japan and thought this is something I would like to do, to write a book to teach people about tofu and how to start a company so they can make it.”

After its release, he and Aoyagi went on a nationwide tour to spread the word about tofu and soy foods. “We bought a big white van and drove about 7,500 miles. I showed slides, we served recipes. It was just lots of fun. And the reception was very positive,” he recalls.

The Book of Tofu and their nationwide tour is credited with helping to launch hundreds of non-Asian commercial tofu makers and offered a whole new culinary experience for many Americans. This tofu movement also gave a boost to existing tofu companies run by Asian-Americans.

One of the companies that started in the US amid the counterculture tofu boom was Phoenix Bean. It has served Chicago for the past 40 years, and makes 28 different tofu products, ranging from soy milk and bean sprouts to tofu cubes – from soft to firm – fried tofu, tofu noodles, yuba and tofu salads.

Jenny Yang is the third owner of the company. She was a regular customer because she and her daughter are lactose intolerant, and decided to quit her corporate job to take it over in 2006. Yang started with six staff and now has 35.

Phoenix Bean is well known in the Asian community for its fresh tofu products, and American celebrity chefs including Rick Bayless and Stephanie Izard also incorporate the company’s tofu in their dishes.

To get more non-Asians in the Midwest to eat tofu products, about 10 years ago Yang ventured into farmer’s markets to drum up interest, which required persistence and creativity.

“It was really fun to interact with the American customer first hand,” Yang recalls. “First they said, ‘OK, this is tofu, this is not cheese. OK’. And then I said, ‘This is plant-based protein, basically’. And then they said, ‘Oh, OK, how do you make this? Where is the soybean from?’ They all think soybeans are from China. And I said, ‘No, actually, it’s 40 minutes away’.”

To help non-Asian-Americans embrace using tofu, Yang developed simple recipes using her products, including tofu with teriyaki sauce, and created eight different tofu salads.

Nowadays tofu is not an uncommon sight in US supermarkets. While it still has not necessarily achieved the widespread popularity of some other imported foods, like yogurt, or become as widely eaten as meat, it has come a long way over the last 150 years in America.

“Over the course of the 20th century, and particularly since the 1960s and 1970s, tofu went from being a very niche product mainly in Asian-American communities to becoming a widespread American food that many Americans know about and many Americans appreciate,” Roth says.

“It’s had to overcome a fair amount of ridicule, but nonetheless, a lot of people have embraced it and enjoyed it.”

Additional reporting by Carolyn Wright