The story of Lotte: how a chewing gum maker in Japan became one of South Korea’s largest conglomerates

- Formed by a Korean migrant in Tokyo in 1948 to produce chewing gum, Lotte today is a global retailing, hospitality and leisure conglomerate

- Founder Shin Kyuk-ho was inspired after seeing US troops handing out gum to children; today its best known product is another gum, sugar-free Xylitol

In 1941, during World War II, a young Korean man decided his ambitions were bigger than the family pig farm. After finishing high school, Shin Kyuk-ho boarded a ship from the Korean port city of Busan to Japan with dreams of becoming a novelist. Instead he would build one of South Korea’s largest conglomerates, the Lotte brand, and become known as Asia’s “chewing gum tycoon”.

It all started with chewing gum.

“Gum has been Lotte Confectionery’s most significant product,” a spokesman for Lotte Confectionery told the Post. “And among that, Lotte’s Xylitol gum has had the greatest impact. It’s often seen as the ‘national gum’ of Korea.” Today, the green and white packs of Xylitol can be found on convenience store shelves around the world.

Shin was born the youngest in a family of 10 children in 1921 in Ulsan, then a small port town in Korea’s southeast. After landing in Tokyo, he wound up delivering newspapers while studying at a technical college. He adopted a Japanese name – Shigemitsu – to help him blend in with his fellow students and later, business partners.

Like many in post-war Japan, Shin became fascinated with all things American. After seeing US soldiers handing out bubblegum to children, he was inspired to form his own company in Tokyo making gum for the Japanese market. The Japanese city was a controversial place for a South Korean to build his business empire – until 1945, Korea was a Japanese colony.

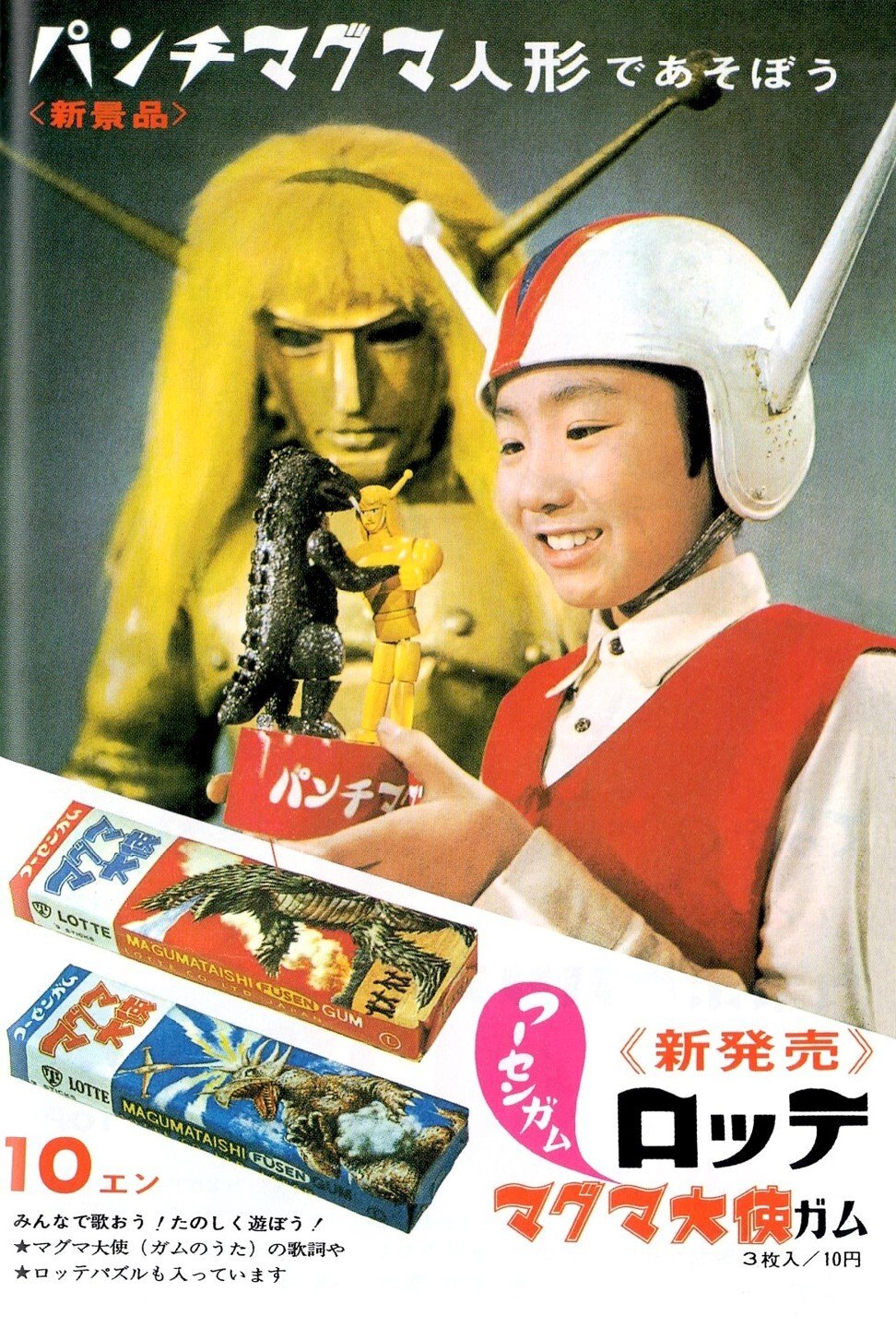

Shin’s company opened for business in 1948, producing gum under brand names such as Cowboy and Mable Gum. The only trace of his literary dreams would be a name: Lotte. It was a name he took from Charlotte, the heroine in Wolfgang von Goethe’s 18th-century novel The Sorrows of Young Werther .

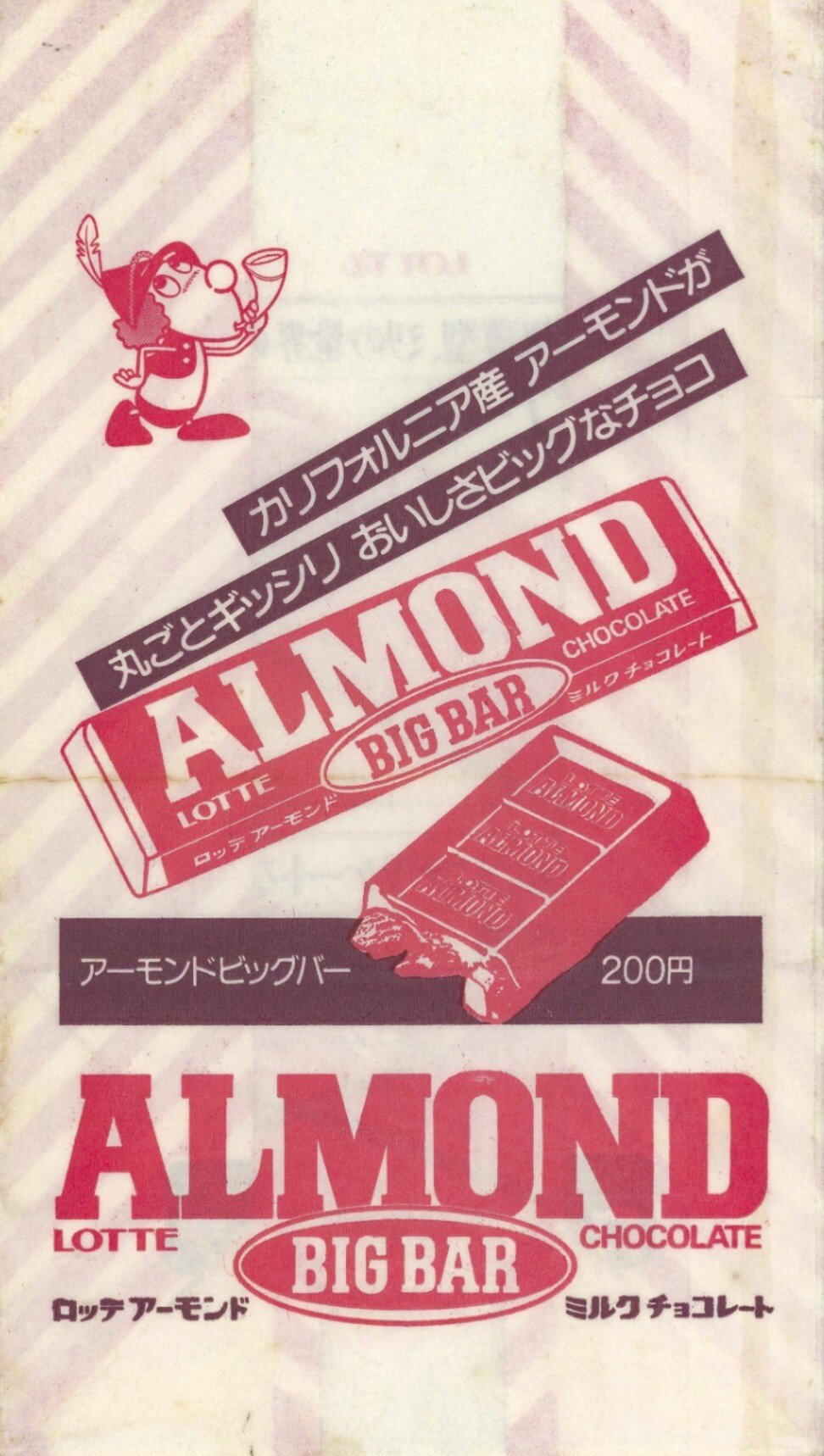

Shin soon expanded into making other food products such as confectionery and chocolate, including the Ghana chocolate line, still popular for its milk chocolate bars. His company sponsored TV programmes and a Japanese baseball team, the Lotte Orions.

Lotte’s success in Japan was unquestionable and Shin’s ability to succeed in a country where ethnicity was so important was a testament to his ambition.

In 1965, Lotte received the gift Shin had been waiting for when Japan and South Korea finally normalised diplomatic relations. This allowed Lotte to expand into Shin’s motherland in 1967, at a time when South Korea was undergoing a period of growth unlike anything the world had seen. True to its roots, Lotte’s first product in Korea would also be chewing gum – but many more products would follow.

Lotte was soon on its way to becoming South Korea’s fifth largest chaebol, family-run conglomerates that came of age during that rapid post-war development. These companies helped turn South Korea from one of the poorest countries in the world into an exporting powerhouse and the world’s 12th largest economy.

But while chaebol such as Lotte benefited from close government ties, those connections often came at a cost, and the South Korean government had demands of its own. South Korea was then at the height of its cold war with North Korea. Eager to build up its military strength, the government was approaching corporations to ask for help manufacturing military supplies. High on its list of candidates was Shin and his Lotte enterprise.

Shin spurned the government’s approach, and so began a long and complicated relationship between Lotte and the South Korean military.

That relationship would eventually lead to the THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defence system) controversy in 2017, when Lotte infuriated Beijing by allowing the US-made missile defence system to be deployed on one of its golf courses.

The South Korean government left Lotte with little choice in the matter, and wound up costing the company billions when Beijing, furious over the potential security threat THAAD posed, launched an unofficial boycott of the Lotte brand, shutting hundreds of stores on the pretext they contained fire hazards and leaving its decades-long push into China in shambles.

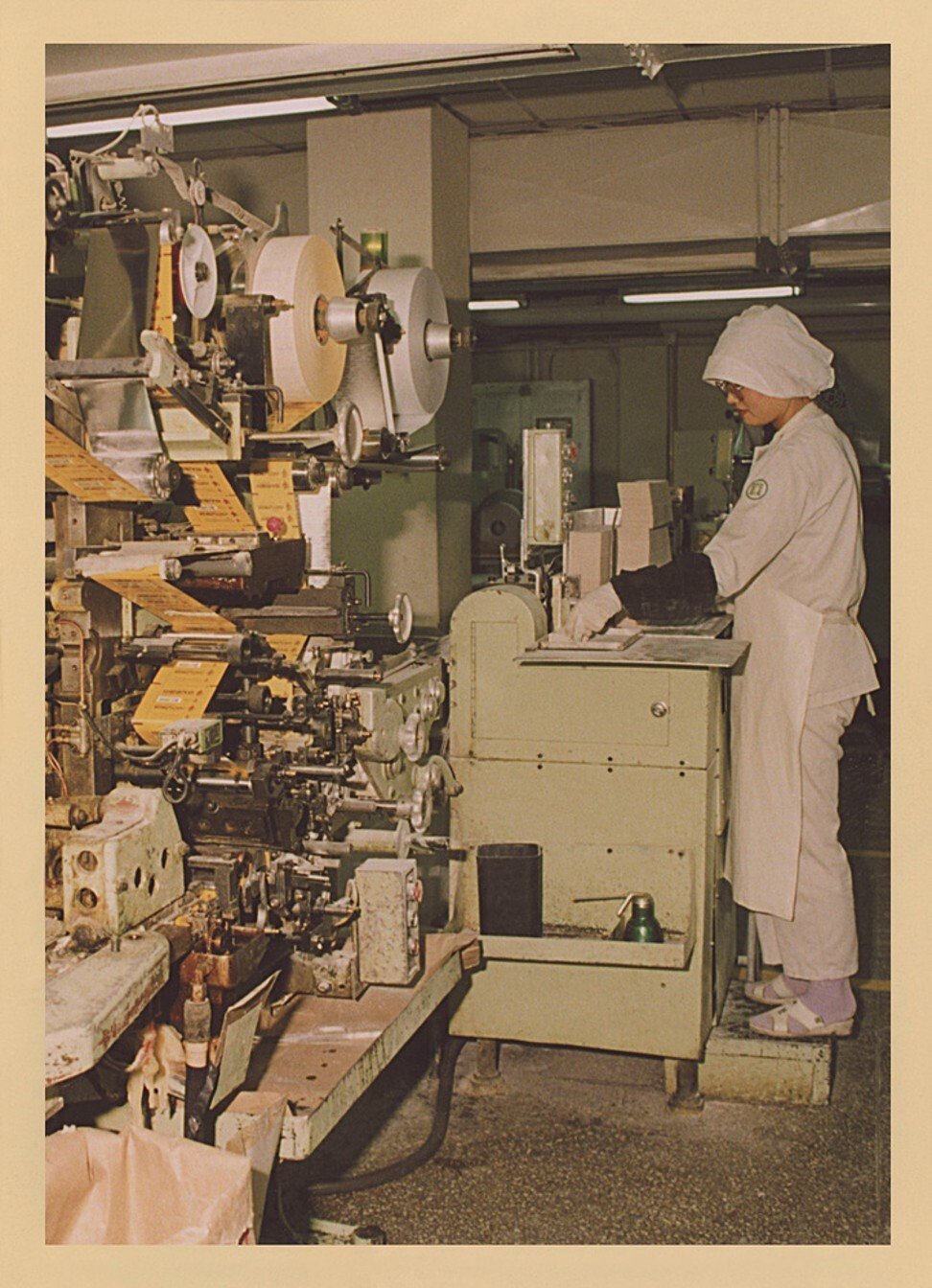

The 1970s and ’80s saw Lotte focus on overseas expansion, building a factory in the US state of Michigan and opening a sales office in Chicago to help sell chewing gum and cookies to the US market.

Then came Lotte’s expansion across Asia, and the launch of subsidiaries in the growing markets of Thailand in 1988 and Indonesia in 1993.

It would move into China the following year, and soon after that launch similar operations in the Philippines and Vietnam.

At home, the booming economy left South Koreans with more disposable income to spend on snacks, which led to the creation of products such as Pepero – a cookie stick dipped in chocolate and sold by the box. There was backlash from the Japanese brand Pocky, which invented a similar snack in 1966 and claimed Lotte had stolen its idea. But Pocky hit a wall in legal proceedings since, at the time, only Pepero was sold inside South Korea.

With Pepero, Lotte achieved a marketing victory most brands can only dream of: an entire day devoted to their snack. Pepero Day, which takes place on November 11 in South Korea, is celebrated much like Valentine’s Day, with young South Koreans lining up to buy packs of Pepero to eat and share with their friends.

The origin of the holiday is unclear – some say it’s the shape of the Pepero sticks that resembles the 11.11 date – but Lotte won big with the holiday. Media reports have pinned Pepero sales for that day alone at 50 per cent of the annual total.

But the company’s biggest success would arrive with a return to Shin’s humble beginnings in the gum industry. Since the 1970s, research had been taking place on something called xylitol, a sugar substitute that was being lauded in Finland for its dental benefits. When it was finally licensed as a food additive in 1997, Lotte pounced on the chance to create a gum with the sweetener, becoming the first in Japan to do so.

It would later take the Korean gum market by storm as a healthier alternative to regular gum, according to a spokesman at Lotte.

“If you lined up all the cases we’ve sold, it would stretch for 269,561km [167,497 miles]. That’s the equivalent of 6.7 laps around the Earth,” the spokesman said.

Lotte’s empire now stretches far beyond chewing gum, and it continues to grow, but its literature-loving founder is no longer at the helm.

Before his death this year at the age of 98, Shin was the last of Korea’s rags-to-riches tycoons credited with helping lift the country out of poverty after the Korean war of the 1950s. He lived long enough to see himself indicted, and to witness his two sons squabble over the empire he’d built after Shin, apparently reluctant to give up control of Lotte, failed to choose an heir apparent.

Appearing in court on charges of tax evasion in 2017, a frail Shin made a scene when he threw his cane to the floor in protest and demanded to know who had indicted him. He reminded the room that he owned everything at Lotte, that it was all his – all while aides rushed to check his blood pressure.

Like the love-struck character who falls for Charlotte in Goethe’s classic novel, Shin’s bond with Lotte seems deeper than that which most other company founders and CEOs have with theirs.

On Lotte’s website, its mission is said to be to “enrich people’s lives by providing superior products and services”. Today the evidence of Lotte’s dedication to that goal, and of Shin’s passion, is written across skyscrapers and store shelves the world over.

Sign up now and get a 10% discount (original price US$400) off the China AI Report 2020 by SCMP Research. Learn about the AI ambitions of Alibaba, Baidu & JD.com through our in-depth case studies, and explore new applications of AI across industries. The report also includes exclusive access to webinars to interact with C-level executives from leading China AI companies (via live Q&A sessions). Offer valid until 31 May 2020.