Nine Christmas traditions explained – from crackers to figgy pudding, holly and mistletoe

Christmas is widely celebrated, but as a festival it predates the Christian era by thousands of years. We look at Christmas myths and their sometimes ancient origins, and the modern traditions that have sprung up around it

It’s impossible to ignore the imminence of Christmas. From October – or September, officially, in the Philippines – the organised among us begin to send cards, the smug enclose letters detailing their offsprings’ glowing successes, and shopping malls everywhere are decked with tinsel and belting out We Wish You a Merry Christmas.

All around us, the colourful spectacle that is Christmas begins to unfurl: lights are strung, trees are decorated, and young children belatedly begin to behave.

So what’s it all about? Even those who understand that Christmas means more than gift-giving and parties might be surprised at the origins of one of the world’s most celebrated dates. It is a Christian holiday to celebrate the birth of Jesus, but midwinter festivals, some with similar traditions, were observed thousands of years before that religion even existed. The pagans, Romans, Crusaders, and even King Henry VIII played a part in the Christmas extravaganza we indulge in today.

The history of Christmas

Ancient midwinter festivities celebrated the lengthening of the day , a turning point between the old and the new year.

Although Christmas draws its name from Christianity, Yuletide (or Yule) was celebrated in pagan Northern Europe , and the tradition had a significant influence on Christmas as we now know it, such as the 12 days of Christmas, the Yule log and the giving of gifts.

The prominence of Christmas Day gained traction after Charlemagne was crowned emperor on Christmas Day in 800 and William 1 of England was crowned on Christmas Day in 1066. Its popularity grew throughout the Middle Ages.

American parents are turning away from a ‘creepy’ and ‘disturbing’ Christmas tradition

Then, following the Reformation of the 16th century, during the reign of Henry VIII, the Puritans tried to outlaw the celebration, condemning it as a Catholic invention. There were riots and protests.

In America, it was banned by the Pilgrims, and became a non-event there for almost 200 years.

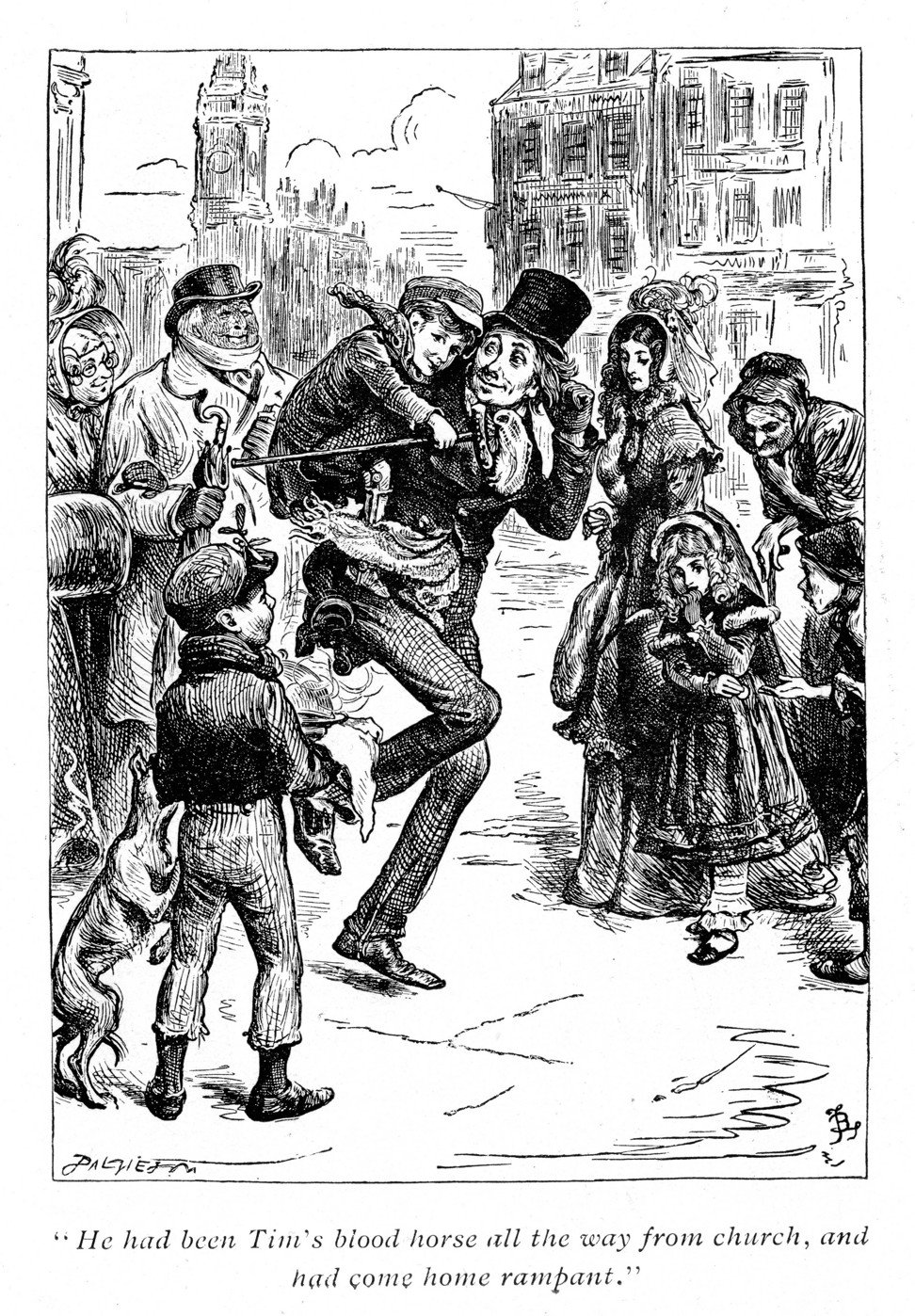

The celebration was resurrected in the mid-1800s in Britain when, writers, fearful that Christmas might die out altogether, began to promote it in their work. In 1843, Charles Dickens wrote the novel A Christmas Carol, which helped to revive the spirit of the season as a family centred affair.

The same season of goodwill and generosity has sustained, born of a hybrid of beliefs – secular and scriptural, pagan and mythical – that have merged and muddied and morphed over millennia to give us the basis for what has become a celebration in more than 160 countries. (China is one of the few countries that do not recognise December 25 as a bank holiday.)

But what of its traditions? Are their origins as blurred as those of the celebration itself? It seems not: it would appear there’s agreement on how those began.

Father Christmas and stockings

A bit younger than Christ, Father Christmas began as Saint Nicholas, a bishop of Myra (in modern-day Turkey), who was a generous man, noted for his kindness to children, upon whom he bestowed gifts having first established their good behaviour during the preceding year.

A shy man who was happier imparting charity anonymously, it is said he once climbed the roof of a house to drop a purse of money down the chimney. It landed in a stocking hung in the fireplace to dry.

After his death in AD340, St Nicholas was buried in Myra, but his remains were stolen in 1087 by Italian sailors and removed to Bari in Italy, greatly increasing the saint’s posthumous popularity in Europe.

As the patron saint of Russia, he was depicted in a red cape sporting a long white beard. In Greece, he became patron saint of (thieving?) sailors; in France, patron saint of lawyers (an anomaly if ever there was one); and in Belgium, patron of children and travellers. By the 12th century, an official church holiday had been created in his honour: December 6, which was marked by gift-giving.

In 1822, American professor Clement C. Moore wrote a poem for his children to describe Santa:

“He had a broad face and a little round belly,

That shook when he laughed, like a bowl full of jelly,

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf.”

Which may have fuelled the idea of today’s Father Christmas: fun, fat and full of friendly benevolence.

Christmas trees

History suggests that German Protestant reformer Martin Luther (1483-1546) was the first man to decorate a tree in anything like the way we recognise today. Coming home one freezing December night, he was struck by the beauty of the stars, their brilliance filtered by the branches of evergreen trees, and the scene inspired him to decorate a fir tree with candles.

Given Martin Luther’s example, it’s not surprising that 16th century Germany took to decorating trees indoors and out with fruit, flowers, confectionery and lights – a habit which the German Prince Albert took with him to England when he married Queen Victoria. The 1848 Christmas edition of the Illustrated News featured a portrait of the royal family gathered under a decorated tree in Windsor Castle, and the trend took off.

Deck the halls with boughs of holly

Holly, ivy and mistletoe are quintessentially linked with Christmas. We stick sprigs of plastic holly into Christmas pudding; we trail snakes of green ivy along mantelpieces; and we pucker up under the mistletoe. Why?

Midwinter in the northern hemisphere was a time of year associated with wailing winds and dark demons. Boughs of holly, believed to have magical powers because they remained evergreen, were placed above doorways to drive away evil spirits. Greenery was also brought inside homes to brighten them up in the bleak season.

Christmas comes early for 30 children at Maggie’s Cancer Caring Centre in Hong Kong

As for mistletoe, that was used by the druids, who revered the plant for the same reason as holly: it was evergreen.

The ancient Celts believed mistletoe had healing powers. It was also regarded as a symbol of peace: the Romans said that enemies who met under mistletoe would lay down their arms and embrace.

Poinsettia

A native of Mexico, the poinsettia is named after Joel Roberts Poinsett, US ambassador to Mexico who introduced the plant to North America in 1828. Poinsettias were used by Franciscan monks in Mexico during their 17th century Christmas celebrations.

According to legend, a small Mexican boy (or girl) realised, on arrival at the reconstruction of the village nativity, that he had no gift for baby Jesus. He hastily gathered some branches from the roadside and bravely – despite the mocking laughter of the congregation – carried them into the church. As he laid them in the manger, a beautiful star-shaped flower appeared on each branch.

Christmas cards

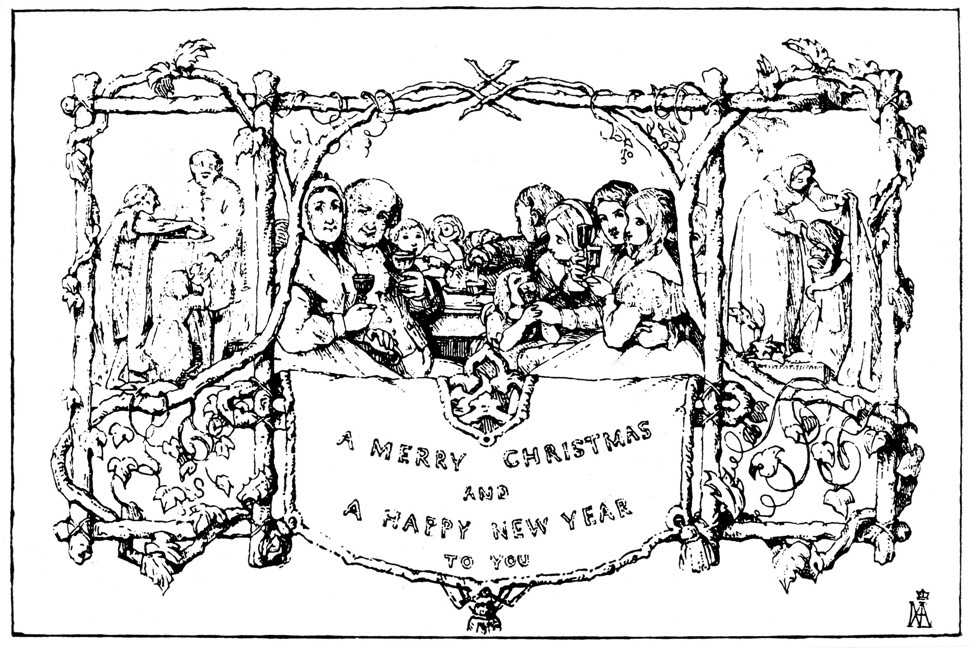

It was Sir Henry Cole, an English public servant, arts patron, and educator, who is credited with creating the Christmas card. As director of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, he found himself too busy during the run up to Christmas 1843 to compose individual season’s greetings to his friends. So he commissioned the artist John Callcott Horsley to do the job for him. The illustration, of a family enjoying the Christmas festivities, bore the message, “A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to You”. The popularity was helped by the new Penny Post public postal service and was promoted further as printing methods improved. By 1860, cards were being produced and posted in large volumes.

Christmas carols

Hymns appeared in 4th century Rome. In the 9th and 10th centuries, Christmas prose was introduced in monasteries in Northern Europe. By the 12th century, a Parisian monk, Adam of St Victor, who recognised the importance of a good backing track, began to derive music from popular songs and marry that to Christmas themed lyrics, and the traditional Christmas carol was born.

They appeared as “caroles of Cristemas” in England in 1426, sung by groups of wassailers, who went from house to house. Some of today’s popular carols – Good King Wenceslas and The Holly and the Ivy, can be traced back to the Middle Ages. The party pooping Protestant Reformers tried to discourage the singing of carols (though Martin Luther continued to write the songs and encouraged their use in worship).

Turkey and other treats

It wouldn’t be Christmas without the food.

Mince pies have been around for ages. Originally called Christmas pies, they date back to the 11th century at which time they usually contained minced mutton. The Crusaders, returning from the Holy Land, brought home a variety of spices. It was deemed important to add three spices (cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg) to the pie to symbolise the three gifts given to Jesus by the wise men. It was considered lucky to eat one mince pie on each of the 12 days of Christmas (ending on January 6).

Over the years, the pies grew smaller and changed from cradle shaped to circular. The meat content was gradually reduced until the pies were filled with a mixture of suet, spices and dried fruit steeped in brandy.

12 drinks for the 12 days of Christmas – plus a recipe for mulled wine

The same dried fruits were later used to make Christmas cake.

Mrs Cratchit in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol made a figgy pudding from figs, breadcrumbs, spices and milk. The pudding is also mentioned in the 17th century carol, We Wish You a Merry Christmas.

For centuries it was traditional to eat goose (or peacock or swan for the wealthy) at Christmas. The change started in the 16th century, when turkey was introduced to England by trader William Stickland, who imported six of the birds from America in 1526. He sold them for tuppence each in Bristol.

Henry VIII was apparently the first person to eat turkey on Christmas Day, but it wasn’t until the mid-1900s that the bird overtook the goose as the popular choice for Christmas dinner. Today, 87 per cent of British people believe that Christmas would not be Christmas without a traditional roast turkey; they eat 10 million of them each year.

Christmas crackers

The Christmas meal wouldn’t be complete without those silly paper crowns pulled out of crackers.

Tom Smith, a baker from East London, invented the Christmas cracker in 1847. In 1840, he travelled to Paris and came across the “bon bon” – almond confectionery wrapped in a twist of paper. He liked the taste so much that he began selling them in London, where they became very popular. Smith, something of an entrepreneur, noticed that his confectionery had become particularly fashionable gifts among sweethearts. So he started to put messages of love into the twists.

One evening years later, sitting by his fire, the crackle of a log gave him a new idea. He started experimenting to try and reproduce the same effect and after a lot of scorching of furniture and fingers, he eventually got it right. He took two strips of thin card and pasted small amounts of saltpetre onto them. When these cards were pulled apart, the friction produced a crack and a spark.

Within a year, Smith’s inventions had become fashionable. They were first called Cosaques, after the cracking of the Cossacks’ whips. It was only 10 years later that they came to be known as Christmas crackers. The coloured paper and novelties were added in following years as competing companies fought for a share of the growing market.