Review | Netflix movie review: Maboroshi – Japanese fantasy anime riddled with annoying teenage angst addresses the trials and tribulations of adolescence

- Written and directed by prolific manga artist Mari Okada, Maboroshi sees an environmental disaster trap a small-town community in a bizarre time freeze

- The film emerges as one giant, lumbering metaphor for teenage challenges, devoid of subtlety and likely to exasperate older viewers

2/5 stars

In the new animated fantasy Maboroshi, an environmental disaster traps a small-town community in a bizarre time freeze, which sends its adolescent residents into an angst-ridden tailspin.

Written and directed by prolific manga artist Mari Okada, the film blends themes of loneliness, insecurity and jealousy into a potent cocktail of teenage disenchantment, but the persistently clumsy symbolism and repetitive confrontations soon overshadow any genuinely insightful commentary about the perils of puberty.

The secluded blue-collar town of Mifuse is rocked to its core following a giant explosion at the local steelworks that literally shatters the sky overhead. This cataclysm enshrouds the town in a dome from which they cannot escape, and soon they come to realise that they are trapped in time as well as space.

While some members of the community spin the event into a religious reckoning, rebranding the site as a “Sacred Engine” that must be appeased, for high-schooler Masamune (voiced by Junya Enoki), this is merely a physical manifestation of his own sense of isolation.

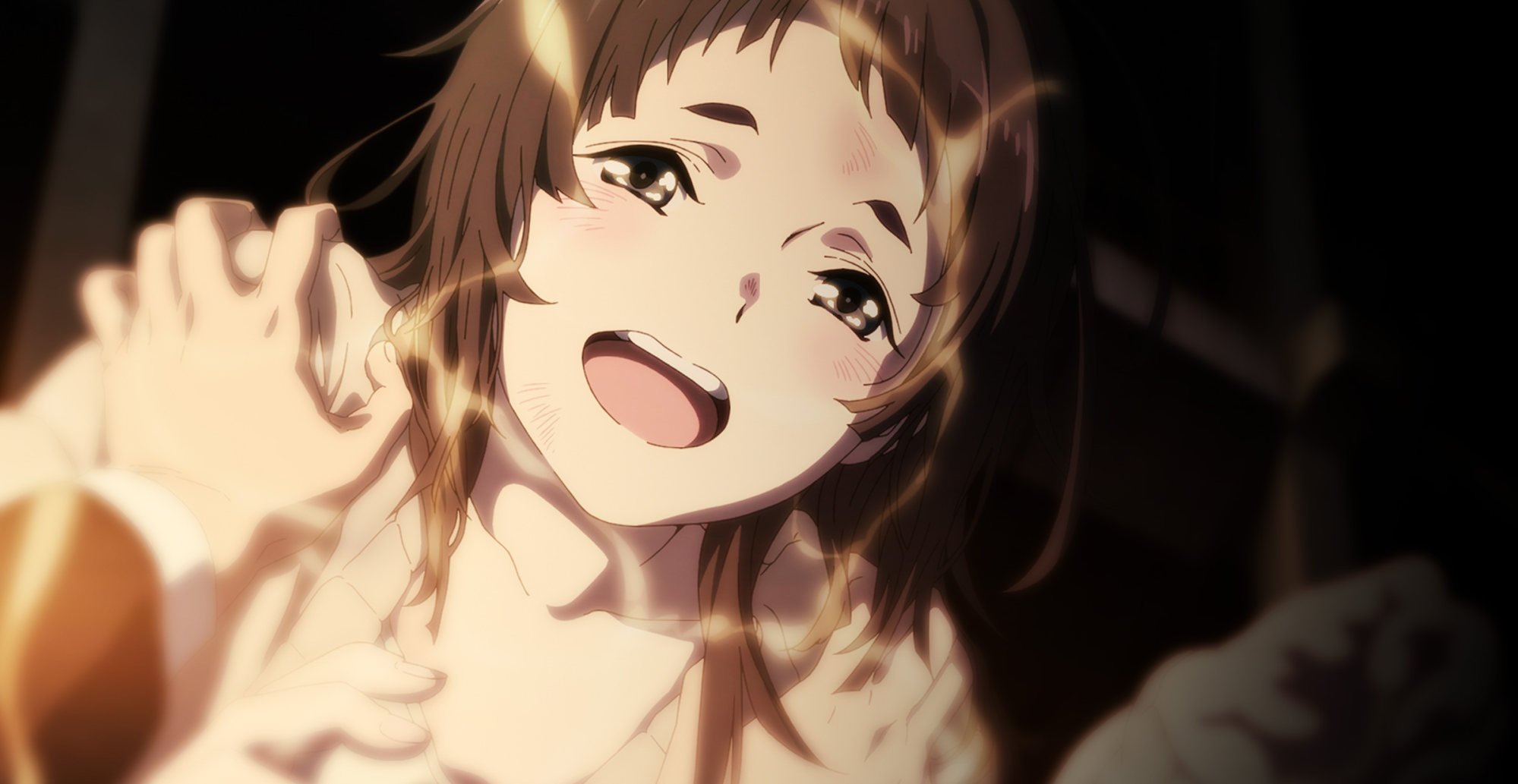

Events come to a head when Masamune is led into the steelworks by Mutsumi (Reina Ueda), a mysterious female classmate, who introduces him to a feral young girl (Misaki Kuno) who appears to be held captive within the factory.

Christening her Itsumi, Masamune is instantly fascinated by her and curious as to where she came from, why she is being kept prisoner and why her social skills are so severely limited.

Maboroshi marks Okada’s second film as a director, following 2018’s Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms, and addresses many of the same themes, as well as employing a number of that film’s key crew members.

Both films deal with young protagonists who are forced to become surrogate parents to abandoned children, while still battling to hone their own understanding of the world around them.

Ultimately, Maboroshi emerges as one giant, lumbering metaphor for the trials and tribulations of adolescence, devoid of subtlety and likely to exasperate older viewers who have long outgrown such trivial insecurities.

Masamune’s crippling sense of isolation from the rest of the world is writ large across the fractured sky that keeps him and the rest of the town imprisoned.

The revelation of Itsumi’s origins will come as no surprise, as Okada ineffectively attempts to pivot the film’s emotional focus towards something more mature.

Inevitably, the lessons learned – to have confidence in your own romantic and artistic disputes as our time on Earth is limited – are perfectly legitimate, but the film seems only capable of expressing them through sustained histrionic bawling that quickly becomes wearisome.