Gay adoption drama directed by a teenager tells Chinese true story of LGBT couple and their child – ‘the world’s strongest family’

- Producing the film was a huge undertaking for Ran Yinxiao, who wanted to explore the difficulties sexual minorities face in starting a family in the country

- China has yet to legalise same-sex marriage or allow couples to adopt, and LGBT filmmakers have felt the effects of increasing censorship in the country’s media

A gay couple adopt a child and start a family together. In China, where many barely acknowledge the existence of the LGBT community, this touching real-life story was made into a movie by 19-year-old Ran Yinxiao.

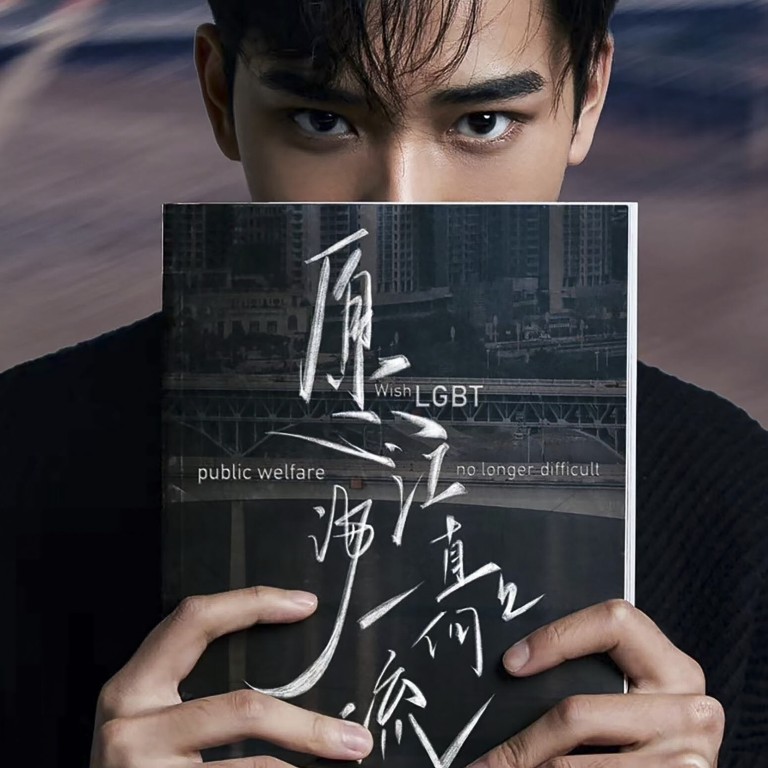

Forbidden Love in Heaven, released in July on several Chinese streaming platforms, follows the story of a man who finds a child on the streets and raises the boy with his male partner.

“This was my bold attempt to explore the difficulties that sexual minorities face in starting a family,” Ran says. “My thinking was that if three different people without any blood ties could start a family, then this must be the world’s strongest family.”

The young filmmaker is one of a number of increasingly vocal activists challenging China’s traditional views of the LGBT community, despite the government’s growing censorship of the issue.

Ran’s film upends the traditional conceptions of marriage and family in China.

Very few filmmakers are incentivised to make queer films, especially feature-length films, because of the lack of funding support and the prospect of the film being banned

“In forming a family, same-sex couples can also raise and care for a child,” Ran says. “And that child’s sexual orientation wouldn’t be affected by the fact that their parents are the same gender.” He notes that the child in his film “became a very successful writer”.

Ran adds, “I wanted to emphasise that an LGBT couple can raise and nurture a child too.”

Shanghai Pride was founded in 2009 and was the largest and longest-running LGBT event on the Chinese mainland. Ran had planned on screening his film at the event’s accompanying film festival, but it was postponed because of Covid-19 restrictions, then cancelled.

The first film Ran directed was the fictional film Backlit Years, which focused on the experiences of LGBT youth at home and at school. He is studying filmmaking at the Communication University of China, in Nanjing, and has shot two more short films.

Forbidden Love received a number of negative reviews on social networking platform Douban, where people criticised the quality of the filming and acting. It was, however, warmly received on Weibo. Even the Global Times, a state-run media outlet, ran a straightforward and uncritical article about the movie.

“The camerawork, performance, soundtrack, script and other aspects of performance were all a mess, but I really appreciate the enthusiasm and courage of this grass-roots creative team,” one reviewer wrote on Douban.

The brutal institutions ‘curing’ China’s LGBT, nonconformist youth

“I hope that the director can learn about film shooting in a comprehensive way; don’t stop filming, keep going and I will keep watching.”

In recent years, LGBT filmmakers have felt the effects of the ever-tightening controls on, and censorship of, China’s media.

Noted Chinese LGBT films such as East Palace, West Palace, Lan Yu and Farewell My Concubine are also banned (a censored version of the latter was later released).

The Oscar-winning film Bohemian Rhapsody, a biopic about the British rock band Queen, was only released after scenes of drug use and singer Freddie Mercury’s relationships with other men were removed.

When Ran first tried to upload a trailer for his film on Chinese streaming websites, it failed to pass review, he says. After editing it to be more “ambiguous”, he succeeded in getting it passed.

Ran’s film does not contain many intimate scenes. It focuses largely on how two men raised their son and how they navigated family life.

Make-up artist monk who cloaked his sexuality is out and proud

Since cinematic releases are almost unheard of for films with LGBT content, little profit – if any – can be made from films like Forbidden Love. Ran scored some funding for the film from an Aids awareness organisation in Chongqing, but he felt the strain of producing a feature-length film on such a tight budget.

“The situation for queer filmmakers in China is overall rather dire at the moment,” says Hongwei Bao, a professor in media studies at Britain’s University of Nottingham. “Very few filmmakers are incentivised to make queer films, especially feature-length films, because of the lack of funding support and the prospect of the film being banned.”

Fan filed a lawsuit in 2015 against China’s media regulator after his documentary on mothers and their gay and lesbian children, Mama Rainbow, disappeared from major Chinese video sites. Though the court accepted the lawsuit, he ultimately lost, and found it increasingly difficult to work in China.

“I found that a lot of my events were not allowed,” Fan says. “I was invited by the Beijing Film Academy to do a screening. And then it got shut down by my professor at the Beijing Film Academy because he thinks I’m perverse, I’m not doing good stuff, I’m harmful.”

Many of those who worked on Forbidden Love are gay or lesbian, but few are entirely open with their families about it.

LGBT couples in China campaign to be counted in national census

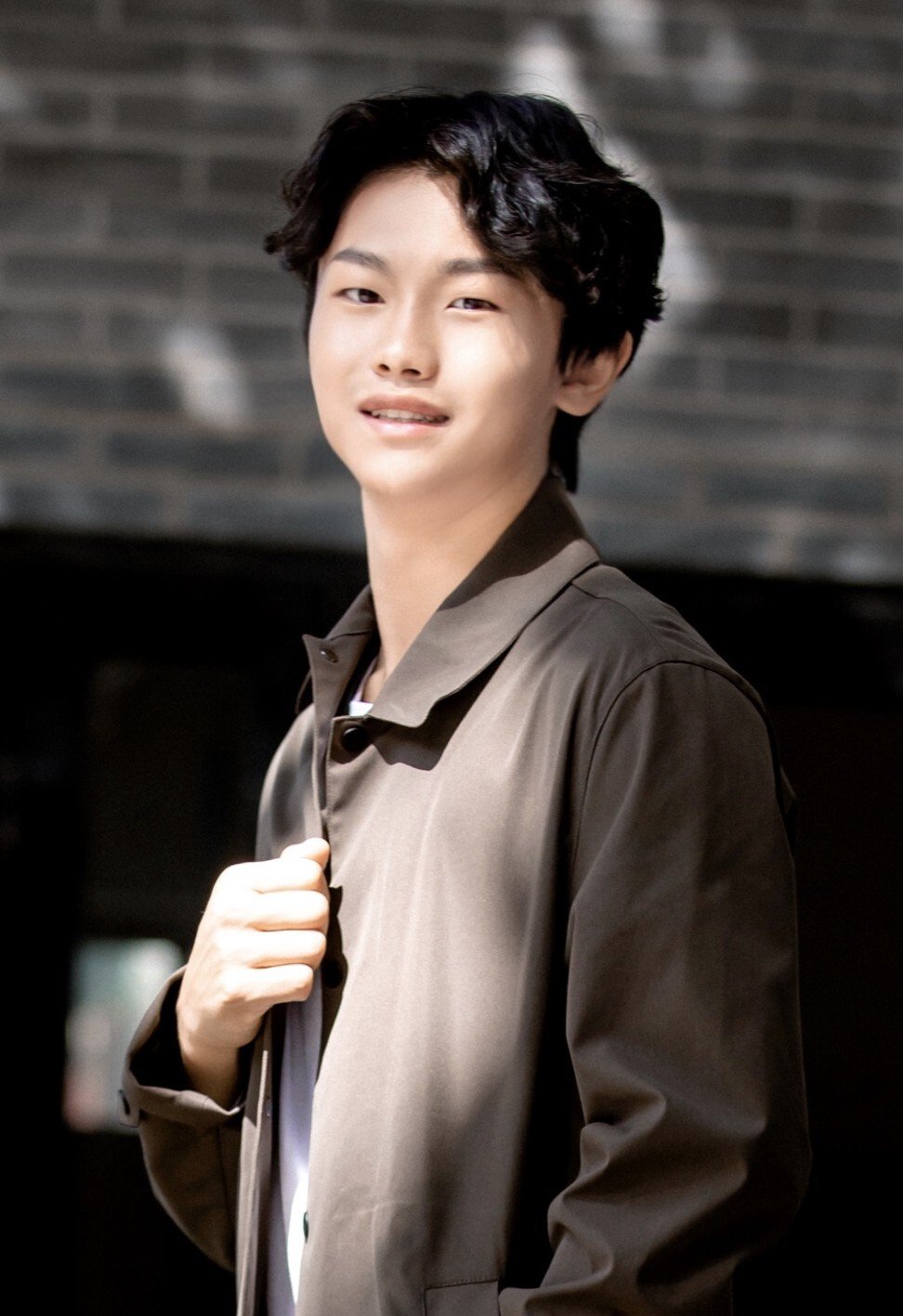

Shooting Ran’s film was a learning experience for some of the actors. “I didn’t really understand this topic, this group,” recalls Zhang Xin, who played one of the fathers. Through his character, Zhang learned more about the LGBT community. He hopes the film’s audiences will as well.

“I hope our film is the start of this acceptance. And I hope that in the future there’ll be more movies of this kind … maybe our movie can be a pioneer, a small pioneer.”

The Chinese name for Ran’s film roughly translates to “wishing that the river will forever flow upstream”. It’s from something he once read about LGBT acceptance in China – that the older generation would rather believe rivers could flow upstream than believe LGBT people exist.

For now, Ran plans to continue making movies highlighting China’s LGBT community, trudging against the river’s current despite the obstacles ahead.

“I think to myself, why do moviemakers exist?” Ran says. “Our camera lens is our weapon. We enlarge the aperture to allow more light to shine on the places of the world that aren’t easily seen.”