Oscar-winning Chinese composer Tan Dun on why ‘Hong Kong is home’, his new role as city’s cultural ambassador and upcoming ‘immersive opera’

- Known for his work on Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and his opera starring Placido Domingo, Tan is Hong Kong‘s new Ambassador for Cultural Promotion

- About to present a new opera in the city, the eccentric composer talks about why he loves Hong Kong, writing a symphony in its streets, and mushrooms

Tan Dun – composer, conductor and, as of December 8, Hong Kong’s Ambassador for Cultural Promotion – is an enthusiastic soul. He loves the city. Not only is it a pearl, he declares, it is a “diamond”.

It’s true that, growing up in Hunan province in central China during the Cultural Revolution, he was under the impression Hong Kong was a sinful place: “a very bad capitalist society with a lot of corruption, all those running dogs”. On his initial visit in 1986, he was surprised not to be robbed. “But actually, my God, this is the frontier of the future – the multicultural future journey of Marco Polo!”

Since then, he claims to have been to Hong Kong “a hundred times”, which may not be strict accounting: Tan’s relationship with facts, like his love of water, is eagerly fluid.

He is someone who can build a concert hall among the canals of Zhujiajiao – nicknamed the “Venice of Shanghai” – through which a river flows as part of a dual musical/architectural experience; or create a “forest” of digital birds, using ancient Chinese instruments and smartphones, in his orchestral piece Passacaglia: Secret of Wind and Birds. His mind and ear seek spiritual harmony between humans and nature.

Less evolved details, however, tend to clog the creativity. Sometimes he tweaks them. For this reason, Elaine Yeung Chi-lan, a former deputy director of the Hong Kong government’s Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD), is sitting alongside him at the Hong Kong Cultural Centre in Tsim Sha Tsui, where he will have his new office.

She’s acting as a human metronome, attempting to keep him in time and to the point throughout the interview. Occasionally, she shakes her head, smiling at the torrent of words.

Somehow, I always thought Hong Kong is my home.

Whatever the statistics, Tan believes he and Hong Kong are forever linked. After all, he got married – to Jane Huang, a Chinese journalist he met in a British bar in New York – in the Tsim Sha Tsui registry office.

The first time he tells the story, they’re in a lift which stopped at that floor. “I said to Jane, ‘Let’s get married!’ Boom. We get our passports. It’s done.” Half an hour later he tells the story again. In this version, the lift doors open, Tan cries, “Oh, wrong place” but Jane says, “Wait a minute …”

In any case, Hong Kong choreographer Willy Tsao Sing-yuen was a witness along with Queen Elizabeth, whose official photograph hung on the registry’s then-colonial, capitalist wall.

“When she passed away, I was actually very sad because I remember my marriage was blessed by her.” Asked for a specific wedding date, he immediately says, “1993.” Yeung interjects: “1994.” Tan responds, cheerfully, “Something like that. I thought it was about 1992.”

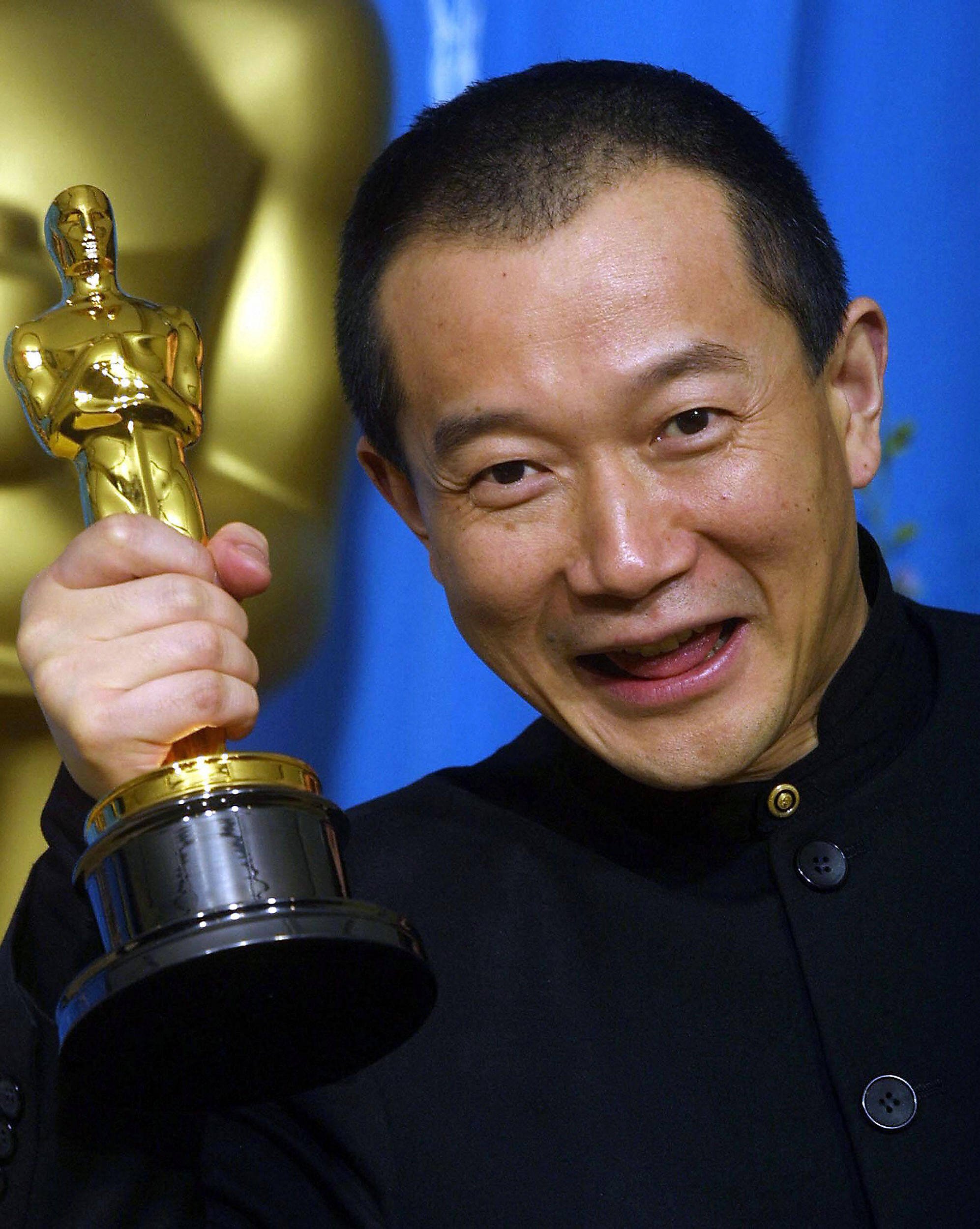

Yeung is the prime mover of Tan’s new, unpaid, ambassadorial appointment. The pair have known each other for 35 years, during which time Tan has won an Oscar and a Grammy (both for his work on Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) and written soundtracks for the wuxia films Hero and The Banquet.

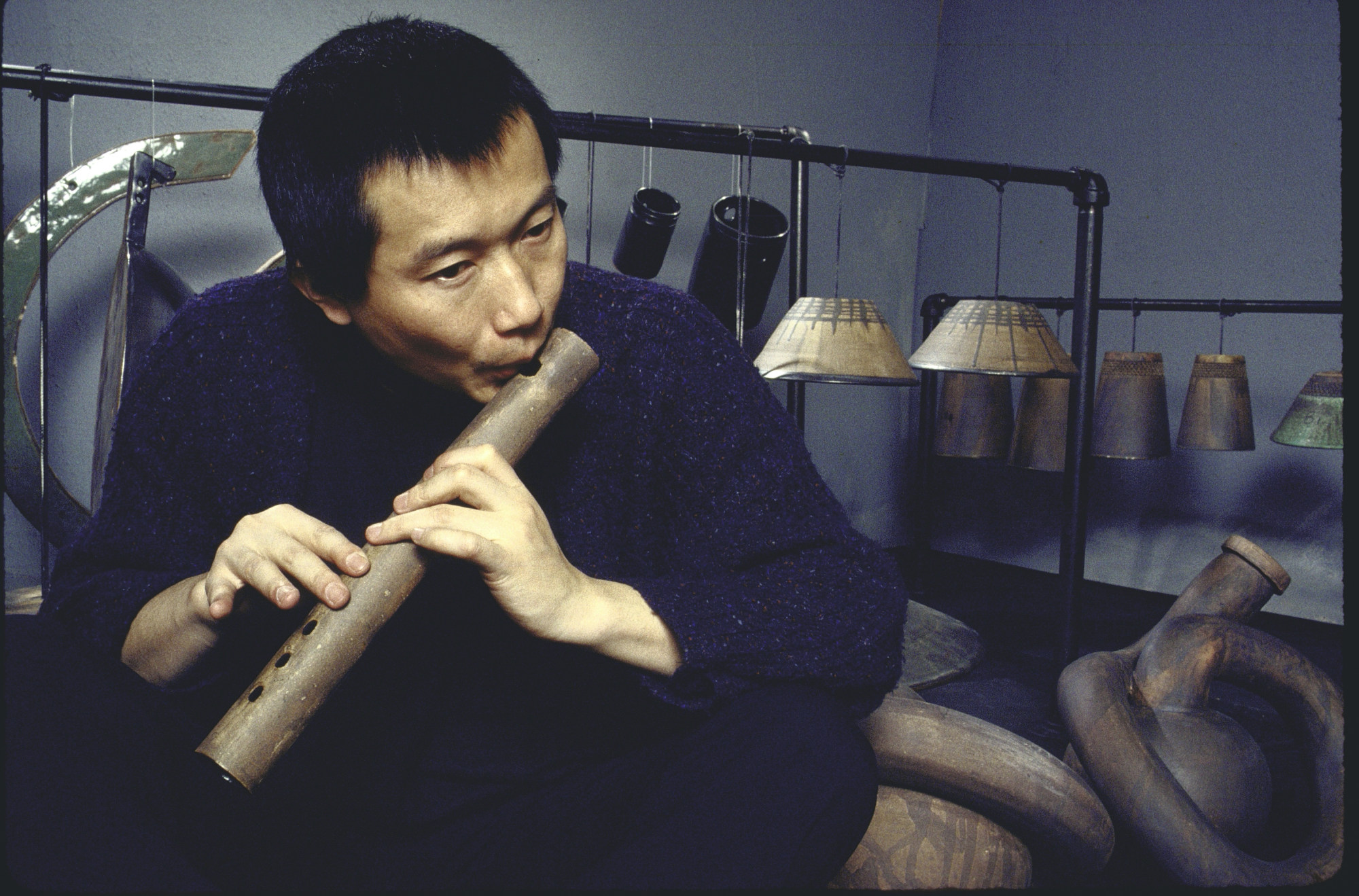

He has created Chinese-themed operas, including Marco Polo and The First Emperor, commissioned by New York’s Metropolitan Opera for legendary tenor Placido Domingo. He has invented what he calls “organic” music for instruments made of water, paper and stone. He has been appointed a Unesco Goodwill Ambassador, with particular reference to his promotion of water as a valuable resource.

For the purpose of this conversation, however, as Yeung says, “The most important thing is that Maestro [Tan] participated in the handover ceremony.” In 1997, Tan presented his symphony Heaven Earth Mankind, which featured replicas of 2,400-year-old bells, and cellist Yo-Yo Ma, in celebration of the restoration of Chinese sovereignty over Hong Kong.

He recalls its creation fondly: “Yo-Yo and I would go to Temple Street [in Hong Kong’s Yau Ma Tei neighbourhood], collect our thoughts in the ancient streets, with the interesting traditions and beautiful food, and we wrote a wonderful symphony.”

Fast-forward a quarter of a century to the 25th-anniversary year of the handover, when Yeung rang Tan on an early autumn night while he was having breakfast in New York. She had been troubled by what she delicately refers to as “that time there were all those things on the streets” – the 2019 protests, followed by Covid. But she felt as though Hong Kong was getting back to normal.

In 2020, Xi Jinping announced China’s 14th five-year plan. “In Hong Kong we are positioned as the hub for international cultural and art exchange but how can we complete this assignment?” says Yeung, who worked in the arts for 38 years before her retirement from the LCSD last month.

“We cannot just boast and say, Oh, we are good.” Nor could she leave it to those in office. “We are the people working with Maestro and other artists. And because I was going to retire, I could propose anything crazy. No one can sack me.”

She asked Tan if he could be a cultural ambassador for the city and, although she had no further details to offer, he agreed.

“Somehow, I always thought Hong Kong is my home,” he says. Does he actually have a place in the city? “No. I don’t want to have any property in my life because I want to be light, to fly any time – to let the spirit be free all the time is the best way to compose.”

In conversation with Tan Dun: Oscar-winning Chinese composer and cultural preserver

Still, he does own a town house in Manhattan’s Chelsea district, which he bought in 2001, shortly after the September 11 attacks and which, he marvels, has since multiplied thirty times in value. “Amazing! Thirty times! I so regret I don’t focus on real-estate business.”

Yeung worked on her proposal. “I had to present the case to get endorsement from the Secretary for Culture, Sports and Tourism [Kevin Yeung Yun-hung],” she explains.

“Artistically, Maestro will be the director to lead us through major projects. Educationally, he can contribute. He can give Hong Kong artists a chance to ride on his international projects, like his July concerts here – Sound of Dunhuang – when he auditioned five local artists to perform. And for tourism, he can promote Hong Kong abroad.”

Six years ago, Tan visited the Chi Lin Nunnery in Hong Kong’s Diamond Hill neighbourhood. “I thought this is the most beautiful Buddhist temple in the world,” he says. “I went at least 10 times! I love this temple – every corner, every stone, every tree has a sense of design. The energy is incredible!”

He wanted to create a musical spectacle, set against Chi Lin’s architecture using five Chinese instruments modelled on those seen in the murals of Cave 172 in Dunhuang. The pandemic contributed to a three-year delay, and Yeung worked behind the scenes. While he was in Hong Kong for his July concerts, Chi Lin’s head nun asked for a meeting.

“By the way, we had a three-truffle mushroom dinner,” says Tan. “And it was completely, my gosh … I thought, we have to do something.” (His appreciation of mushrooms was heightened through his friendship with fungus lover and American composer John Cage. The friendship began, according to Tan, when Cage gave him US$20 while he was playing the violin, as a doctoral student at Columbia University, on a New York street.)

5 ancient Chinese instruments come alive in rousing Hong Kong concert

At sunset on Saturday and Sunday in the courtyards of Chi Lin Nunnery, Tan will present Purity . Transcendence – what he calls “an immersive opera” with music, film, dance, drama. It will, promises the press release, provide the audience “with a soul-purging experience”.

“I am lucky we have so many good angels in this city,” Tan says. Yeung adds, from a less ethereal perspective, “These angels are all civil servants who are so powerful, in a way, because we know how to manipulate, to get the budget, to anchor a certain project. He doesn’t know the difficulty because I dare not bother him.”

She turns to him and suddenly repeats, “You do not know! You do not know how closely we are working with your team to set a date. We know you have all sorts of ideas but we have to lock down the date at least.”

He agrees he has many ideas. One possibility, in this maritime city of Hong Kong, is to create another water-based music-and-architecture marvel, as he did in Zhujiajiao.

Perhaps it will be on an island off Sai Kung, in Hong Kong’s New Territories. In the meantime, his ambassadorial work began on December 4 when he gave a lecture, in Mandarin, entitled “Architecture and Music”, in Nan Lian Garden, which is next to the Chi Lin Nunnery.

It has been transformed into a “sound garden”; until December 11, this green oasis nestled among the many construction cranes of Diamond Hill will reverberate to the sound of ancient instruments recreated from paintings of long ago.

During his lecture, he used a couple of young women to illustrate his points. Each time one of them was about to begin performing, Tan – who’d sat down for a second – would leap from his seat and continue talking. He can’t help himself.

Afterwards, he gave his verdict on how his first task had gone: “I thought it was great!”