From Tesla cars to Brazilian waxes, being smooth is everything in today’s world – but why, artist wonders

- ‘Why are we thinking about beauty without edges?’ asks artist Jes Fan. His works’ rounded edges and fluid forms hide unexpected materials like blood and urine

- A trans male who recalls a ‘draconian’ education at Diocesan Girls’ School in Hong Kong, Fan’s art also questions the construction of race and gender identities

Artist Jes Fan is fascinated by the beautiful and the repulsive. His exploration of the contrast between them leads him to question our standards of beauty, shaped as they are by consumerism.

“In the age of Teslas and Brazilian waxes, everything has to be smooth and [without corners]. Beyond feminine beauty, in architecture you see highly digitally rendered curvature,” he says.

“Why are we thinking about beauty without edges? It stoops to consumerist needs, it’s a very accessible idea of beauty.”

Fan finds beauty in the grotesque. The rounded edges, glossy surfaces and fluid forms that constitute Fan’s visually seductive aesthetic disguise the most unexpected materials.

Urine, melanin, and blood are suspended within what look like blown glass orbs in both Form Begets Function and Function Begets Form. The works were commissioned for the 22nd Biennale of Sydney, which opened in June this year and runs until September.

Sex hormones are captured in similar glass orbs – progesterone in Systems III (2018), and testosterone coupled with beeswax solidified in the form of an unassuming candle in Testo-Candle (2016), works that broach the idea of gender without stigma.

“When you’re growing up, society is your school and vice versa. Hong Kong doesn’t always embrace alternatives or people who don’t fall under the norm

Fan’s work also addresses our construction of identities based on race and gender. Coming from a family in manufacturing – his father ran a toy factory and his grandparents a textile factory in Hong Kong – he has always been interested in how things are made, and this curiosity extends to how social and cultural norms are formed.

The artist says his practice is charged by three questions: “How are things made? What are things made of? And how can we make them better?”

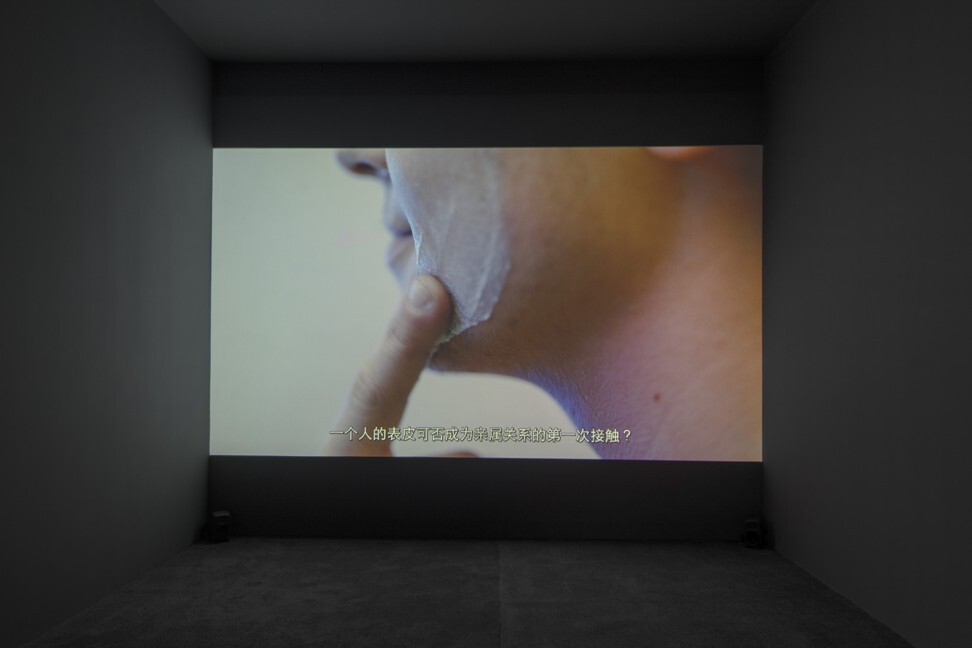

“How is my gender made, how is my race made? How is kinship made? That’s what really pushes me,” says Fan of his motivations. These themes come together in Mother is a Woman (2018), a video Fan made that presents itself as an advert selling a face cream.

The cream is shown being developed in a lab, where a monotonous voice-over begins with the words: “Mother is a woman, beyond a beauty cream.” The contents of the cream include secretions of the hormone oestrogen from Fan’s mother.

The narration continues, mimicking the tone of typical skincare marketing highlighting the exclusive and exotic ingredients and method used in creating the product. “We use artisanal technology to extract the purest oestrogen from my mother’s urine … as your skin absorbs my mother’s oestrogen you are effeminised by her.

“Mother is a woman who can be applied however you want, daily, weekly, whenever you miss home. Kin is where the mother is.”

Born in Canada but now based in Brooklyn, New York, Fan says the experience of growing up as a queer child in Hong Kong, being trans male, and transitioning from being part of an ethnic majority to a minority in the United States, punctuates his work.

“It has a lot to do with being in the queer community and seeing the world as a gendered place, through a gendered lens,” Fan says. “When you’re growing up, society is your school and vice versa. Hong Kong doesn’t always embrace alternatives or people who don’t fall under the norm.”

While Fan concedes that “the oppression that happens [in Hong Kong] is less intense or direct [than elsewhere]”, he still “felt a lot of pressure being ‘smoothed out’. And I didn’t grow up seeing queer icons or adults”.

Fan attended Diocesan Girls’ School, where the education was “draconian and colonial” and made a stronger imprint on him than society or his family.

He later attended Li Po Chun United World College in Hong Kong, after which he went to the Rhode Island School of Design in the United States. His approach to making art has been influenced by all three institutions.

“I think in the very beginning, I was working so hard ultimately to prove other people wrong, to prove that I was talented and that I had ideas to contribute and I wanted to make meaningful work,” Fan says.

Since then, his approach and his work have both evolved.

“Right now I feel like I’m over that reactive phase. How can I offer my perspective on the world in a non-reactive way? I think this lockdown during Covid-19 has been especially sobering and allowed me to reflect on that,” says Fan.