Spies in Hong Kong: from mainland Chinese agents and Japanese infiltrators to Taiwanese defectors and local pirates, a history of espionage in the SAR

- Spies have been part of Hong Kong since the earliest days of British rule. Some were caught, others fled, but for a few suspects we might never learn the truth

On June 8, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor warned the city’s universities not to let their students be “easily indoctrinated” after being “penetrated by foreign forces” bent on “brainwashing”; forces who either “want to undermine the Chinese government, or have ideological prejudices against China”, expressing that she had “no doubt” that “ulterior motives” were at play, confirming her belief that “these external forces are at work”.

Which external forces were these exactly? She declined to say.

As far back as the beginning of Hong Kong’s tenure as a British colony, in 1841, there has been an element of clandestine intrigue about the place, imagined or otherwise. In Hong Kong, spooks have always been among us.

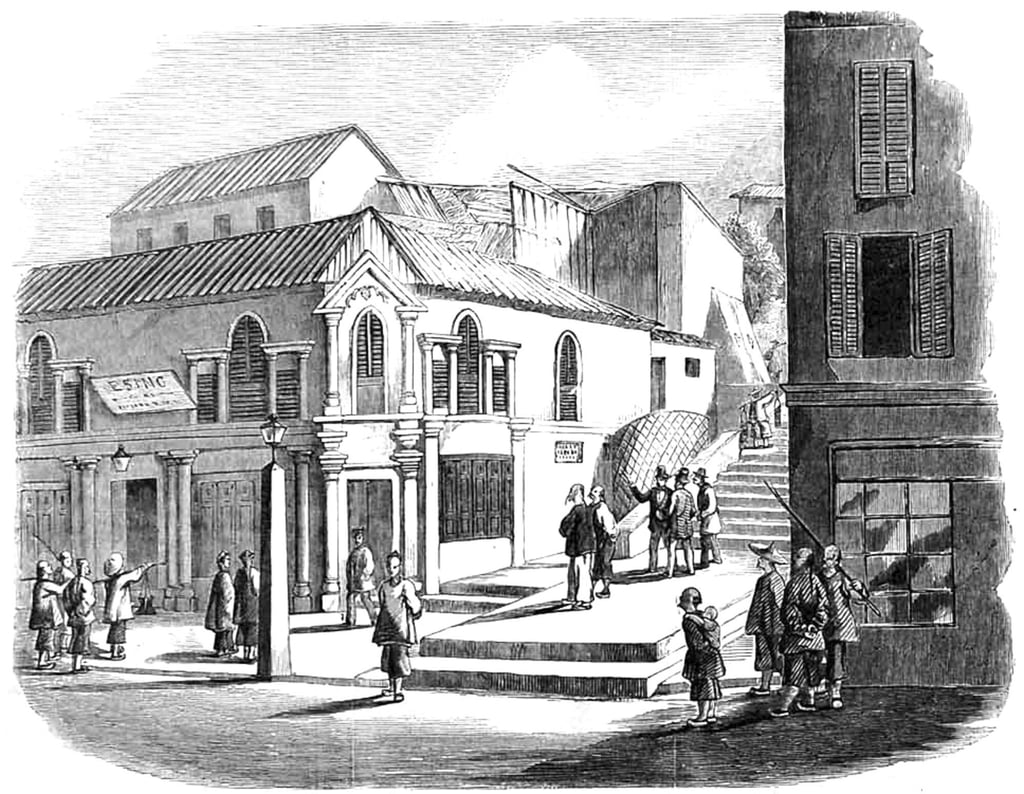

In 1857, with the second opium war under way between Britain and China, the emerging city was plunged into its first spy panic. But when it came to identifying the source of the subversion, the culprit did not appear to be a highly trained military infiltrator or a suave secret agent. That January, when several hundred Europeans – including soldiers at the British garrison – were poisoned by arsenic in bread baked by a Chinese-owned store, the spirit of that time led many to conclude that the Esing Bakery was a front for mainland infiltrators.

Once the nausea and vomiting subsided, the bakery’s owner, Cheong Ah-lum, appeared in the dock – apparently a bemused local businessman unable to account for the tragedy. But others believed Cheong to be a master spy, and his shopfront a sly ruse.

By August of that year, the war was not going well for Britain. As far afield as the American capital, The Washington Union newspaper reported that there was an “Extirpation Association’’ dedicated to undermining British control of Hong Kong and returning it to Chinese rule. The association’s “sleeper” spies were said to be numerous in the colony, rumour-mongering that the British were close to defeat, that food supplies were running low and mass starvation beckoned; these subversive elements were thought responsible for the Esing Bakery poisoning, and could do it again.