Why Baptist University students' stand-off over Mandarin courses isn't about "free will" but xenophobia against China

HKBU row has nothing to do with protecting Cantonese; it’s all about the fear and paranoia caused by our inevitable integration with the mainland

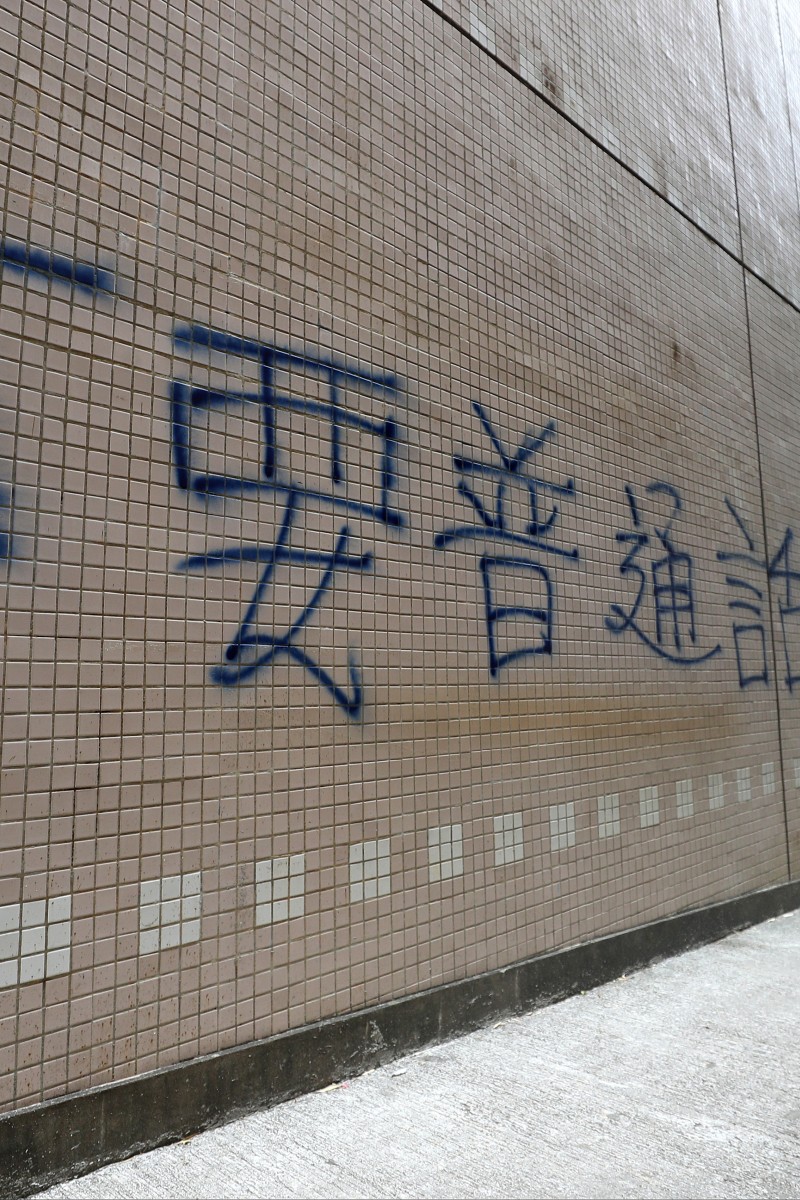

"No Putonghua" was spray painted in Cantonese near the Baptist University Sports Centre in Kowloon Tong.

"No Putonghua" was spray painted in Cantonese near the Baptist University Sports Centre in Kowloon Tong.Online footage of an eight-hour stand-off between Baptist University (HKBU) students and their teachers over a compulsory Mandarin test has once again sparked outrage in our not-so-quiet city. With the controversy culminating in a day-long campus occupation, punctuated with speakers comparing the students’ suspension to the persecution of Jesus Christ, the level of hysteria has reached a new high.

As far as we can tell, citywide discontent over ongoing national integration is far from burning out.

Despite accusations of “Cantonese erasure” by powerful forces, the students at the centre of the uproar have insisted that their demands have nothing to do with the localist movement.

Andrew Chan Lok-hang, convenor of Societas Linguistica Hongkongensis – a group that promotes the use of Cantonese (but sounds like a Latin book club) – said the clash was a result of their desire to protect the use of Cantonese in the city. Others, such as HKBU student union president Lau Tsz-kei, said the issue was a matter of freedom of choice, claiming the university has no right to decide what is best for them.

While it is plainly attractive to distance themselves from a violent far-right movement, it is hard to ignore the undertones of xenophobia that permeate their rhetoric. Their arguments about “free will”, though sound in principle, also apply to the compulsory English courses that have long been in place at the university and other institutions. Indeed, when asked about this inconsistency on RTHK, Lau justified it by saying that English is an international language while Mandarin is “only good in China”. This response does not address his “double standards”. By saying that mandatory courses are acceptable if they are more useful than Mandarin, Lau has betrayed his principle and revealed his true intentions.

Even if we are to accept Chan’s explanation as a well-meaning attempt to protect Cantonese, it is hard to see any direct link between introducing compulsory Mandarin lessons at university and the loss of the local dialect. Lifelong use of a language is unlikely to be overridden by weekly (or even fewer) lessons in another, and obtaining proficiency in a new language does not mean losing your ability to use the mother tongue.

In any case, the 2016 Population Census indicated that 89 per cent of the local population still use Cantonese as their first language, with a mere two per cent mainly using Mandarin.

This helps us affirm what we all knew intuitively: the protests are not about some romantic notion of free will and protecting Cantonese, but about the fear and paranoia caused by national integration.

Although some people partly blame the government for the city’s current situation, it is high time we recognise the fact that national integration is inevitable and start to embrace it.

Chinese, especially Mandarin, is our national language and we need it to remain competitive with mainland cities.