With ‘roasts’ and ‘diss tracks’ cropping up everywhere, has ‘cancel culture' gone too far?

The online act of ‘getting rid’ of people can be problematic because it causes a herd mentality where rational thinking takes a back seat

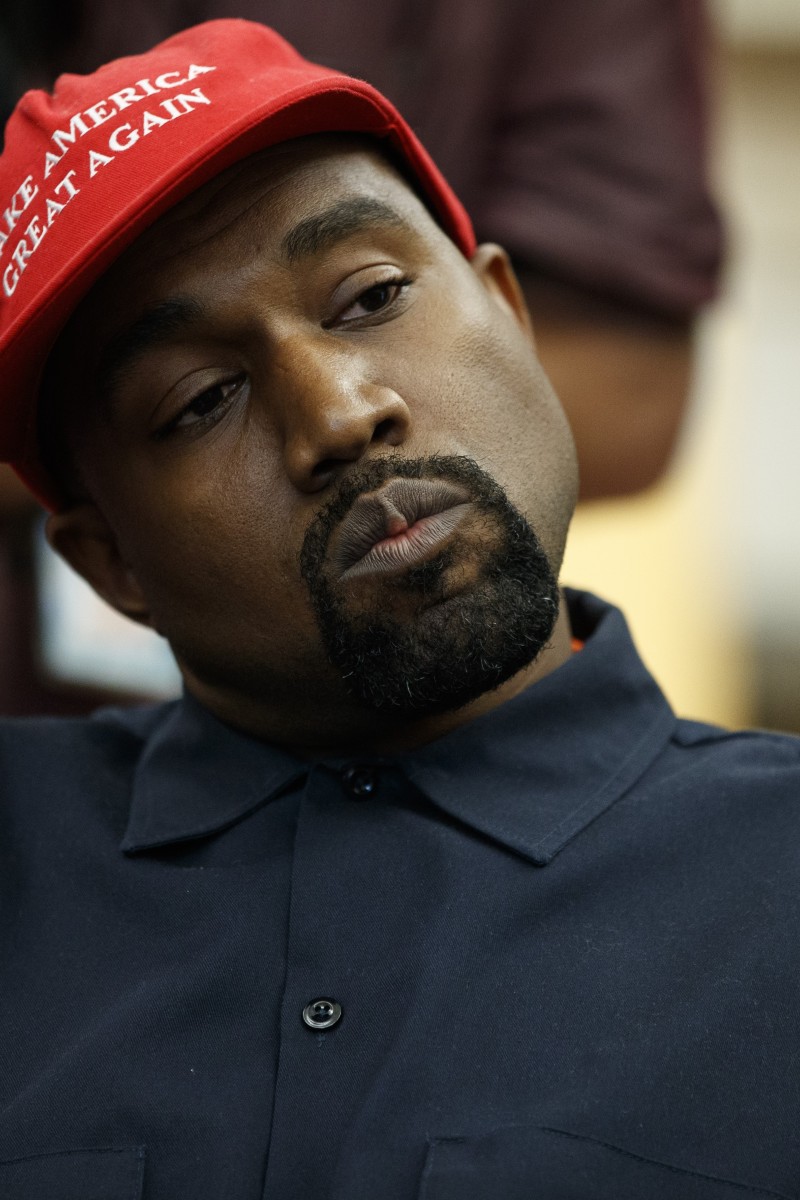

Rapper Kanye West’s comment on slavery caused outrage on social media.

Rapper Kanye West’s comment on slavery caused outrage on social media. In mid-2018, American rapper Kanye West said in an interview: “Slavery for 400 years? That sounds like a choice.”

What followed was an outpouring of outrage on social media, and a single-minded desire to “cancel” West emerged. The “cancelling” culture is popular online. When somebody or something is no longer worthy of public support, they are “cancelled”.

Present-day young people care a lot of about political correctness, which is why the “cancellation” of people and companies for their un-PC, racist views, for example, is becoming increasingly accepted. What are the implications of this trend and where does one draw the line between right and wrong?

One university student's conflicting relationship with technology and social media

This “cancellation” culture is deeply rooted in our heritage and goes way back. Using public favour to determine a person’s fate has, since the Roman era, been a popular concept. Although that type of brutality (think throwing people to the lions) is now obsolete, it remains in more subtle ways in modern times.

The herd mindset which produces these outcomes is more pronounced online than in real life. People on the internet don’t feel responsible for their actions. As part of a group of “cancellers”, they may not even be aware of the potentially disastrous repercussions the culture entails.

Some might argue that “cancelling” is for the greater good. For example, some view West’s incendiary comment that slavery is a choice as completely unacceptable, and say his “cancellation” is justified.

Letters from the dorm: The Instagram Egg, the Super Bowl, and mental health awareness

There were also calls to “cancel” actress Emma Watson, too, because she once said that “feminism is not inclusive”. She publicly apologised and began to educate herself on gender equality. Afterwards, Watson felt like she could help share her views on the “new and diverse definition of feminism” as a UN Women Goodwill Ambassador. In these cases, “cancelling” may be viewed as a rightful response or one that helps bring about a positive outcome.

On the other hand, the “cancelling” culture sometimes goes too far. Take, for example, the era of “diss tracks” in 2017/18. These “diss tracks” or “roasts” – songs created with the sole purpose of criticising a target – became all the rage on YouTube and other platforms. What began as making lighthearted fun of others became highly publicised feuds: competitions in which one would vilify one’s opponent, as they called for the other’s “cancellation”. These attacks are thinly disguised attempts at cyberbullying, which convince people to glorify the “cancelling” culture.

So, here’s the question we ought to answer: should “cancelling” be cancelled? Maybe not. Extreme “cancellers” use slander and defamation. When they try to “cancel” others like that, they aren’t thinking critically. Thinking before typing, having empathy, and not judging things at face value can help minimise the trend’s harmful effects and maximise the beneficial ones.

So, while West’s comment on slavery were inexcusable, so is the argument that his entire life should be “cancelled”.

Edited by M. J. Premaratne