- Sprinters like Jamaica’s Elaine Thompson-Herah and US hurdler Sydney McLaughlin have broken records on the bouncy yet smooth track

- The surface, made by Olympic supplier Mondo, is made of three-dimensional rubber granules that ‘maximise the speed of the athlete’

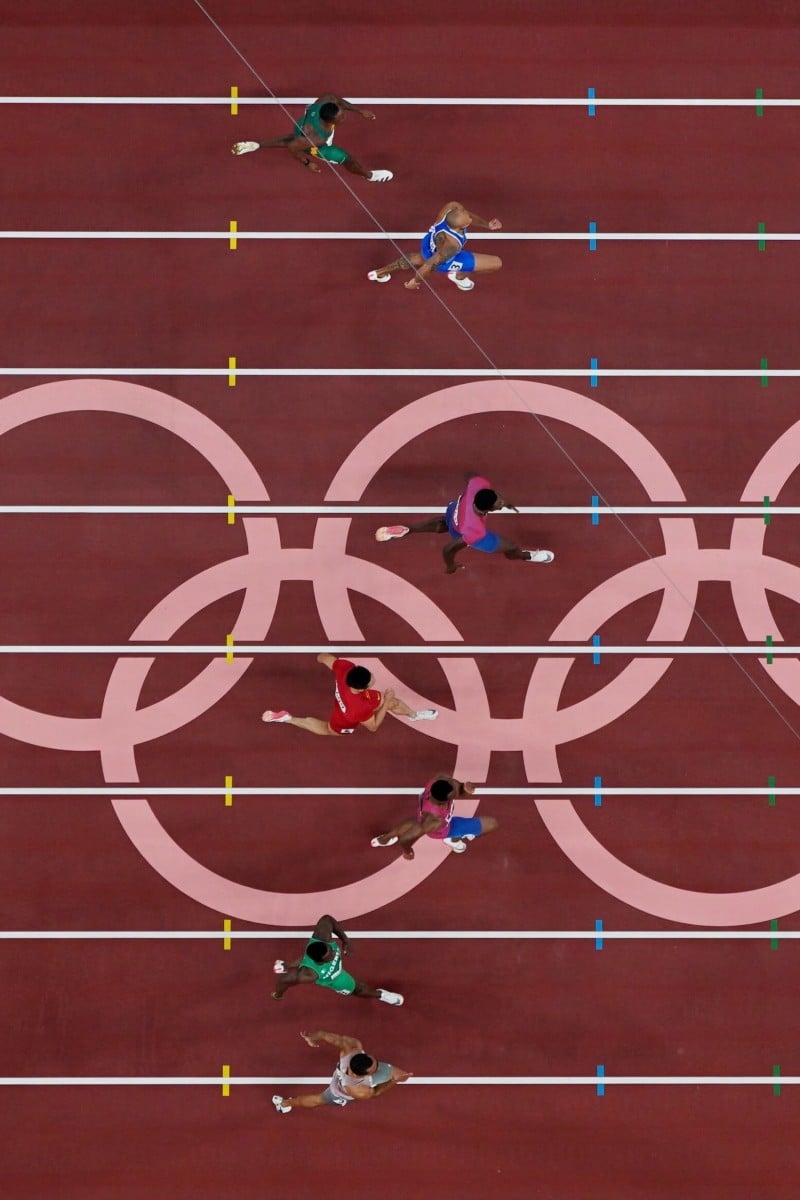

There’s no denying Olympic athletes are fast, but the track at the Tokyo Games may also be helping them out. Photo: Reuters

There’s no denying Olympic athletes are fast, but the track at the Tokyo Games may also be helping them out. Photo: ReutersThe Jamaican sprinter and her Olympic-record time captured everyone’s attention. What’s under foot, though, might have been a factor when Elaine Thompson-Herah broke a 33-year-old Olympic record in the women’s 100 metres.

Runners are certainly on track to setting personal, Olympic and possibly even world-record times over the next week at the Tokyo Games - and the brick-red track may have something to do with it.

Jamaica's Elaine Thompson-Herah crosses the finish line to win the women's 200m final during the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. Photo: AFP

The company responsible for the track is Mondo, which has been around since 1948 and been the supplier for 12 Olympic Games. This particular surface, according to the company, features “three-dimensional rubber granules specifically designed with a selected polymeric system that are integrated in the top layer of Mondotrack WS that are added to the semi-vulcanised compound. The vulcanisation process guarantees the molecular bond between the granules and the surrounding matter, creating a compact layer.“

Translation: It’s speedy.

“Feels like I’m walking on clouds,” US 100-meter sprinter Ronnie Baker explained. “It’s really smooth out there. It’s a beautiful track. One of the nicest I’ve run on.”

Hong Kong’s b-girls have their sights set on the 2024 Olympics

Is it really that fast?

Maybe. Sometimes, it’s just fast runners in tip-top shape who make it look fast. Only time will really tell. The track also has been baking in the Tokyo sun with little use, making it extra firm.

“Oh, it’s fast,” American 800-metre runner Clayton Murphy said. “Might take world records to win.”

When was the track installed?

The track went in over four months, from August to November 2019. It hasn’t seen much action since the surface was put in, but athletes are breaking it in with style.

“You just feel it, man, you just feel it,” South African sprinter Akani Simbine said. “You know what a fast tracks feel like. And for us, this track feels really quick and I am looking forward to running quick on it.”

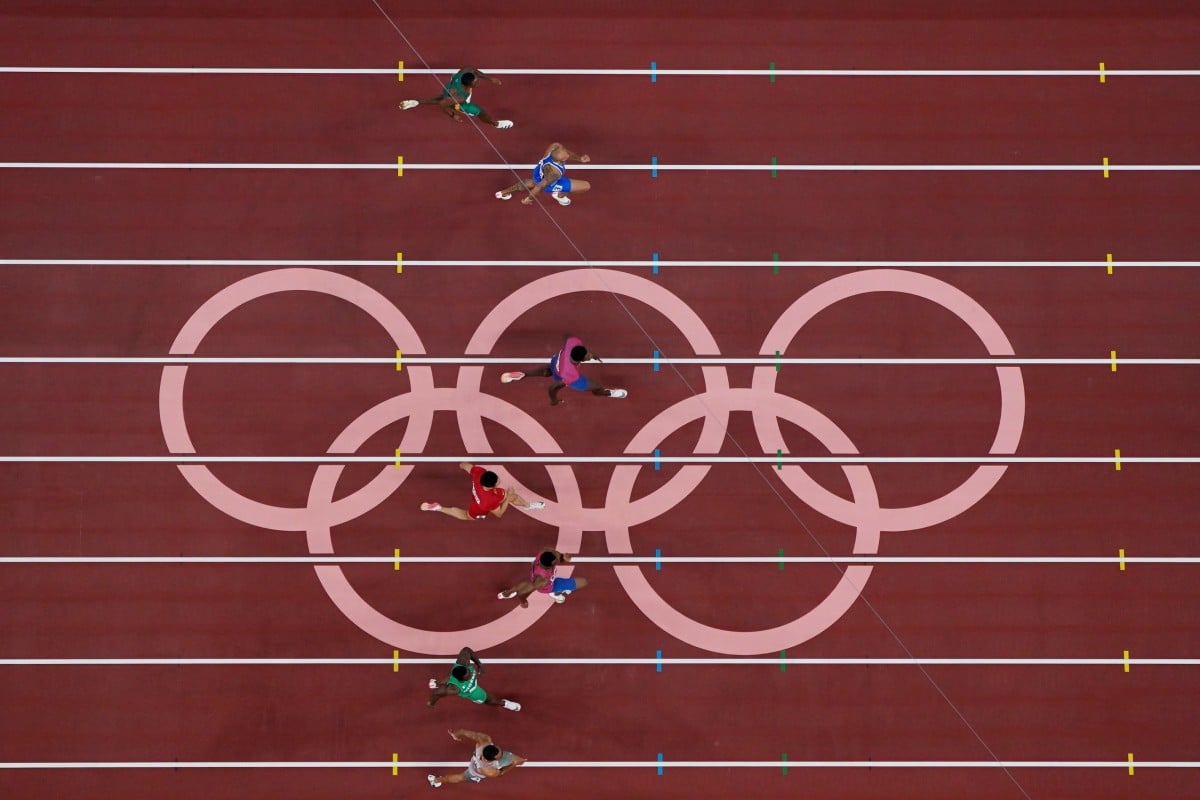

(R-L) Italy's Lamont Marcell Jacobs, South Africa's Akani Simbine and the US's Fred Kerley compete in the men's 100m final during the Games. Photo: AFP

Why is it so bouncy?

Mondo says on its website that the main objective was to “maximise the speed of athletes and improve their performance.” The top layer is vulcanised rubber, to help with elasticity. There are also “air-filled cavities” in the lower layer, which assist with “shock absorption, energy storage and immediate kinetic response.”

More to the point: It helps racers fly down the track.

“Some tracks absorb your motion and your force,” American 400-metre hurdler and world-record holder Sydney McLaughlin said. “This one regenerates it and gives it back to you. You can definitely feel it.”

Olympic gold medal winner in skateboarding has advice for you

What world records may fall?

Keep close watch on the men’s and women’s 400 hurdles. McLaughlin set the mark (51.90 seconds) on June 27 at the US Olympic trials, breaking the record that had belonged to teammate Dalilah Muhammad. They will be the gold-medal favourites on Wednesday - and may break the mark again.

Karsten Warholm of Norway recently broke the men’s 400 hurdles mark when he went 46.70. He eclipsed a record that had stood since 1992. Can he break it again?

“Maybe someone else will do it,” Warholm cracked. “I’ve done my job.”

Gold medallist Karsten Warholm of Norway celebrates on the podium with silver medallist, Rai Benjamin of the United States and bronze medallist, Alison Dos Santos of Brazil. Photo: Reuters

Do the shoes help, too?

The other factor in these records could be the technological advances in spikes. Nike’s Vaporfly model of shoe shook up the world of distance running a few years ago, with carbon-plated technology credited for helping runners shave minutes off their times. That sort of technology is moving its way into the spikes for sprinters.

Thompson-Herah also has a theory on fast times after running 10.61 seconds to break the Olympic mark of the late Florence Griffith Joyner. “My training,” she said. “Doesn’t matter the track or the shoes.”