- When a deadly infection swept through the isolated town of Nome, Alaska in 1925, Balto and a relay team of sledge dogs travelled for six days over 1,000km in a raging blizzard bringing life-saving medicine

- A new study reveals Balto had genes that may have helped the dog thrive in the extreme Alaskan environment

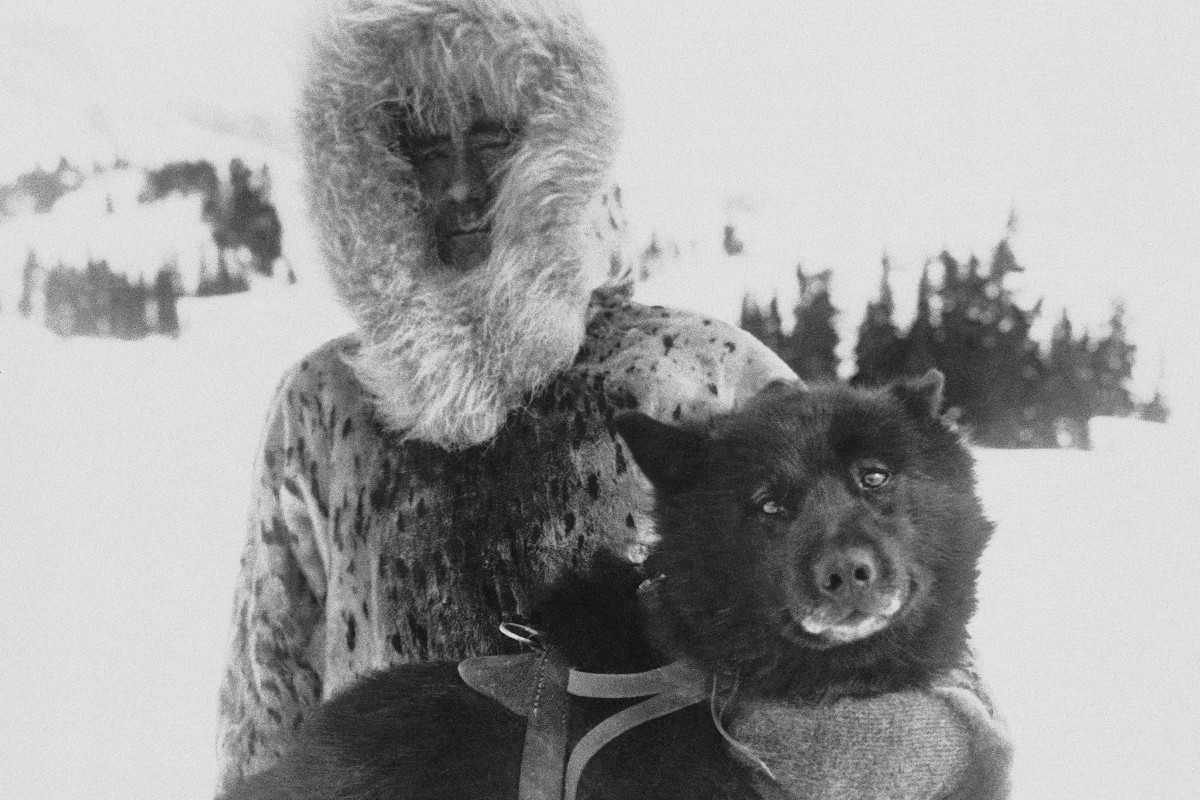

A portrait of Gunnar Kaasen and his dog Balto, who led a sledge-dog team that brought lifesaving medicine to Nome, Alaska in 1925. Photo: AP

A portrait of Gunnar Kaasen and his dog Balto, who led a sledge-dog team that brought lifesaving medicine to Nome, Alaska in 1925. Photo: APIn 1925, a handsome male sledge dog named Balto led a 13-dog team that braved blizzard conditions during the gruelling final 53-mile (85-km) leg of a 674-mile (1,088-km) dogsled relay, bringing life-saving medicine to the Alaskan city of Nome during a diphtheria outbreak.

Balto was feted as a hero, the subject of books and films, and the dog’s taxidermy mount still stands on display at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. But that was not the end of Balto’s magnificent deeds. Scientists have extracted DNA from a piece of Balto’s underbelly skin from the well-preserved museum mount and sequenced the dog’s genome as part of an ambitious comparative mammalian genomic research project called Zoonomia.

Balto’s genome, the scientists found, possessed certain gene variants that may have helped the dog thrive in the extreme Alaskan environment and endure what is now called the Serum Run. Balto, belonging to a population of working sledge dogs in Alaska, also was found to have possessed greater genetic diversity and genetic health than modern canine breeds.

Can dogs cry? What’s the meaning behind those teary puppy eyes?

“Balto personifies the strength of the bond between human and dog, and what that bond is capable of,” said Katie Moon, a postdoctoral paleogenomics researcher at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and co-lead author of the study published in the journal Science.

“Dogs not only offer comfort, support and friendship to humans, but many are actively bred or trained to provide vital services. That bond between human and dog remains strong, 100 years after Balto’s job was done,” Moon added.

As diphtheria – a serious and sometimes fatal bacterial infection – spread among Nome’s people, its port was icebound, meaning antitoxin would have to be delivered overland. Sledge dogs were the only viable option. Balto was among about 150 dogs in a relay lasting 127 hours through temperatures of minus-50 degrees Fahrenheit (minus-45 degrees Celsius).

The researchers examined Balto’s genome as part of a data set of 682 genomes from modern dogs and wolves and a larger assemblage of 240 mammalian genomes, including humans.

Balto’s genome showed lower rates of inbreeding and a lower burden of rare and potentially damaging genetic variation than almost all modern breed dogs. Balto was found to share ancestry with modern Siberian huskies and Alaskan sledge dogs as well as Greenland sledge dogs, Vietnamese village dogs and Tibetan mastiffs, with no discernible wolf ancestry.

Born in 1919, Balto was part of a population of sledge dogs imported from Siberia, dubbed Siberian huskies – though the study showed that these dogs differed substantially from modern Siberian huskies. Balto had a body built for strength and not speed, disappointing the breeder, who had the dog neutered.

Elephant in the dining room: Australian start-up makes mammoth meatball

Balto’s life after the Serum Run was a complicated one involving human exploitation and later salvation. Balto toured the United States for two years on the vaudeville circuit, then ended up on display with other dogs from the sledge team in a Los Angeles dime museum – a lowbrow exhibition – and was mistreated.

A visiting Cleveland businessman saw Balto’s plight and arranged to buy the dogs for $1,500. The money subsequently was raised by the local community in Cleveland. In 1927, Balto and canine cohorts Alaska Slim, Billy, Fox, Old Moctoc, Sye and Tillie were feted in Cleveland with a downtown parade, then spent the remainder of their lives cared for at the local Brookside Zoo. After Balto died of natural causes in 1933, the dog’s mount was placed at the museum.

“His story really highlights how working dogs become functionally heroes,” said study co-lead author Kathleen Morrill, a senior scientist in genome analysis at biotech company Colossal Biosciences. “These specialised dogs don’t know that what they do has such gravity in people’s lives, but their genetic adaptations set them up to be the best animals for the job.”