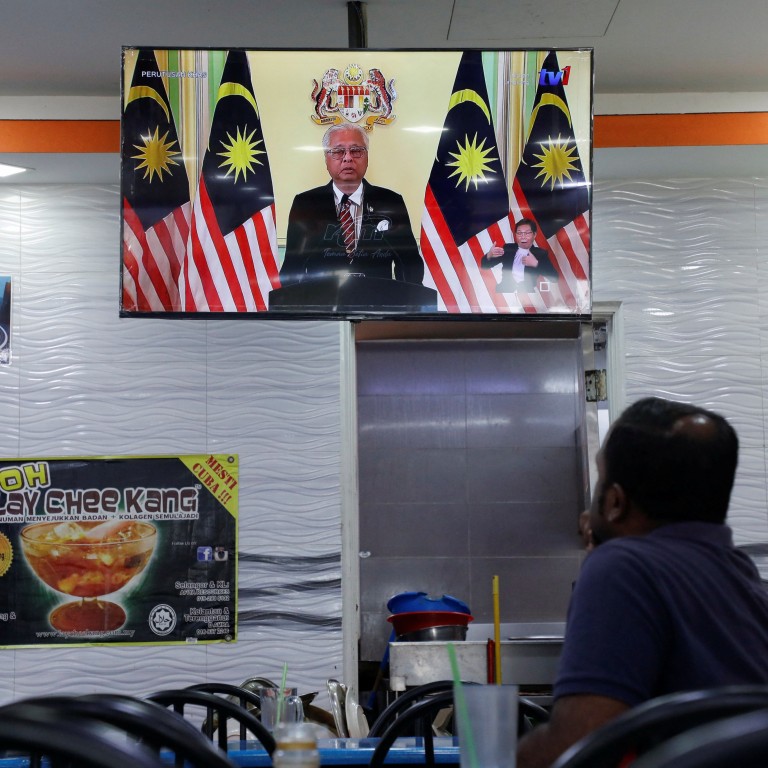

Explainer | Malaysia election: Umno faces fierce fight for Malay bloc, youth vote, and a supermajority

- Analysts say it might be a ‘tall order’ for any group to win a supermajority this time, given the larger number of parties and coalitions in the fight

- At least three coalitions that include Umno and PAS will vie for the Malay-Muslim vote, which accounts for two-thirds of the population, while first-time youth voters are a wild card

New battle lines

In every national election, the battle for the Malay-Muslim vote is fiercest, given the bloc accounts for more than 60 per cent of Malaysia’s 32 million people.

This fight has traditionally been between Umno and long-time foes from the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS), but recent political realignments mean there are now three distinct coalitions vying for the valuable Malay vote.

Besides the Umno-led Barisan Nasional, PAS has allied with Umno-splinter party Bersatu to form Perikatan Nasional (PN) while the opposition Pakatan Harapan is Malay-led and has several strong Malay leaders.

“There are three major coalitions with credible Malay representation so naturally the Malay votes will be split,” said Adib Zalkapli, a Malaysia director with political risk consultancy BowerGroupAsia.

Another factor that may throw political forecasts into a tailspin is the inclusion of at least 1.14 million new registered voters aged 18-20, accounting for about 5.4 per cent of the 21 million total voters, who received the right to vote after parliament in 2019 approved constitutional amendments to lower the voting age from 21 and to allow automatic registration of new voters.

“They will only come out if somebody goes and grabs them. If nobody reaches out to them, then the participation rate among the younger voters will be similar to the general pattern,” Chin told This Week In Asia.

A numbers game

Control of the government would require a simple majority of 112 out of the 222 parliamentary seats up for grabs.

But the Umno-led BN has been accustomed to holding a supermajority in the lower house. Before the 2018 polls, they had won two-thirds of the seats in the lower house in nearly all of the past general elections, allowing them to push ahead with policies and legislature virtually unchallenged.

While not impossible, it may be a tall order for any side to secure a supermajority as there are more parties and coalitions all jostling for a piece of the same pie, according to Shazwan Mustafa Kamal, associate director with corporate advisory firm Vriens & Partners.

“For Umno, they’ll need to carve out a pact with political allies to secure numbers they need to be in government,” Shazwan said.

With broader choices for voters, analysts do not expect any single party or coalition to win nearly enough seats to secure a simple majority in this election.

Even the current administration was formed based on a pact, albeit restive, between BN and PN to make up the numbers.

Although relations between Umno and Bersatu – the respective lead parties for BN and PN – have hit rock bottom, political survival dictates that you can make friends out of enemies.

“BN and PN have shown that they can work together to form the government, so it could happen again,” BowerGroupAsia’s Adib said.