The Manchurian candidate: why China’s interest in the Philippine election is under scrutiny as Duterte prepares to leave office

- Politicians being manipulated by foreign powers are a real-world concern in the Philippines, and talk has now turned to the possibility of a ‘Manchurian candidate’ in the 2022 polls

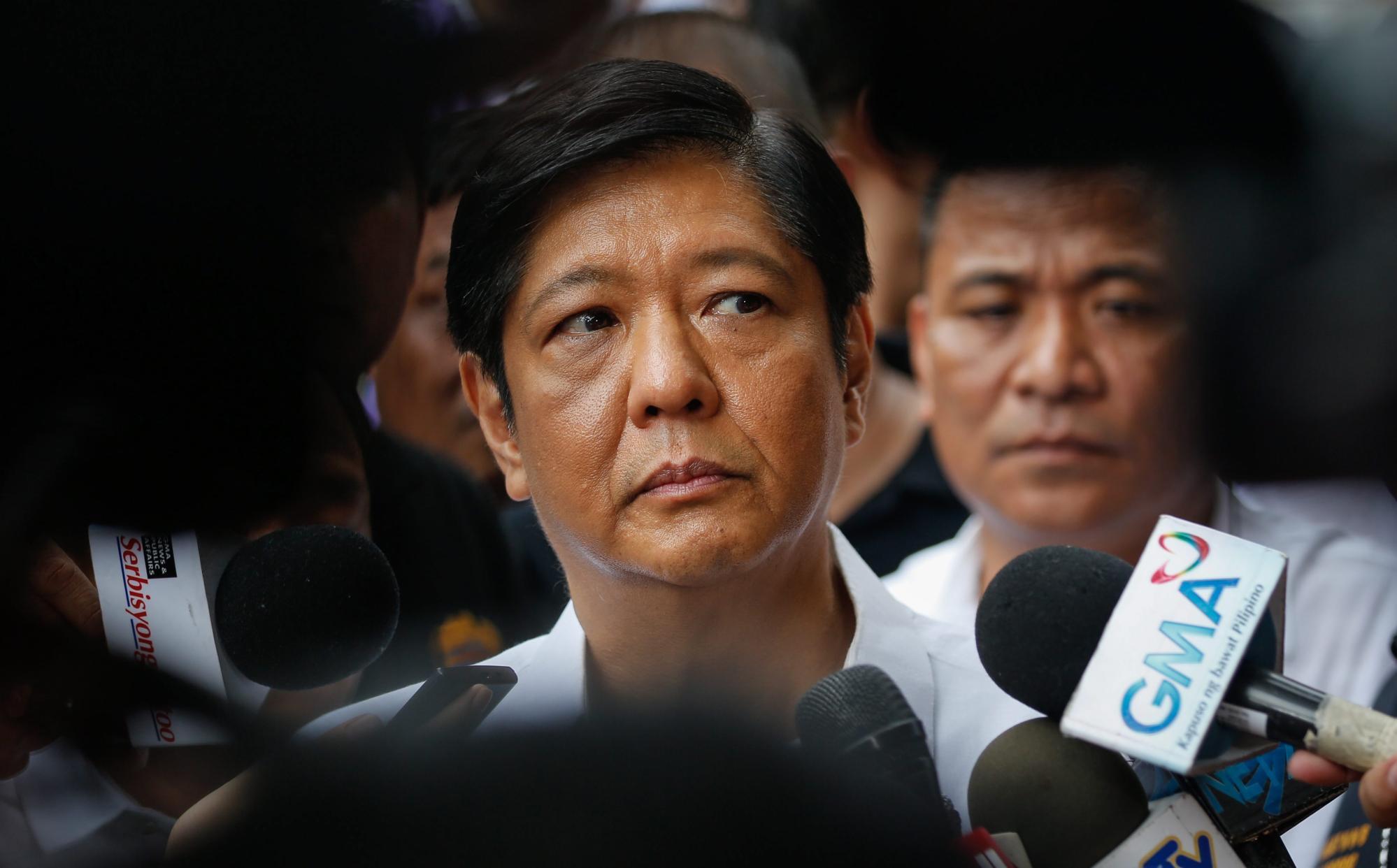

- The CIA once steered the pro-American ‘Amboy’ Ramon Magsaysay into office, but analysts believe China will wield influence now, and the dictator’s son Ferdinand Marcos Jnr may be its pick

That term, for a politician used as a puppet by a foreign or hostile power, was made famous by a 1959 fictional Cold War thriller in which the son of an American political family returns from service in the Korean war having been brainwashed by Chinese and Russian communists.

Seven Philippine presidential hopefuls, from ‘Bongbong’ Marcos to Leni Robredo

Ramon Casiple, co-founder of the Manila-based think tank Novo Trends PH, said “the big framework in this election that people should look at is: which candidates would each superpower prefer not to win”?

“The US cannot afford to lose the Philippines. So this election will be a serious battle, going beyond the simple ambitions of each candidate,” he said. “A lot is at stake.”

But anxiety in the Philippines’ intellectual circles is largely focused on whether China intends to play a role in shaping the outcome of next year’s elections. One the one hand, despite Washington’s pledges to engage with Asia on trade on a multilateral basis and to come to Manila’s aid if its sovereignty is under attack, its domestic politics will make this challenging.

On the other hand, Beijing’s offer of loans and investments - even though data shows the economic benefits are not as great as the Duterte administration has claimed - will be hard to resist for any newly elected president hoping to lead the Philippine economy out of the doldrums.

China’s larger presence and influence in the country has contributed to fears among the public of being crowded out - a rise in Chinese nationals working at offshore betting shops in Manila before the pandemic pushed up property and rental prices. Beijing’s ongoing assertiveness in the disputed South China Sea areas claimed by the Philippines has also fuelled mistrust among Filipinos towards their larger neighbour, according to a range of public opinion surveys.

The China hand

Many Filipino analysts believe that China, which has worked to bring the Duterte administration closer, has already picked its favourite. That’s Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jnr, the son and namesake of the late brutal dictator. He is thought to be favoured because his father established diplomatic ties with China 46 years ago.

For Renato de Castro, a professor of international studies at De La Salle University, Duterte was the “Manchurian candidate” of 2016.

“We don’t have evidence beyond reasonable doubt but there’s circumstantial evidence,” he said.

Shortly after Duterte’s election, the first diplomat the new president allowed to visit him and offer congratulations was the Chinese ambassador, Zhao Jianhua, who served in Manila from 2014 to 2019. In 2016, Zhao met Duterte more times than any other foreign diplomat.

South China Sea aerial arms race catches Southeast Asia off guard

De Castro claimed Zhao was so close to Duterte he could visit the presidential palace “during the wee hours in the morning”.

He also said a source from the Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs told him that Zhao had taken very ill “but Beijing didn’t want to bring him back because of his very important role, his influence on Duterte”.

While This Week in Asia has not been able to independently verify this statement, Zhao did set a record as the longest serving envoy in Manila sent by Beijing since 1975 by staying in the role for five years. Most stayed from two to four years.

Zhao is currently vice-president of the National Institute for South China Sea Studies.

Two other sources separately confirmed to This Week in Asia that only Zhao, among all foreign envoys, could phone the Philippine president directly on his mobile phone, bypassing the Philippine foreign secretary.

In July, former Philippine foreign secretary Albert del Rosario said he had received information that Chinese officials had been “bragging that they had been able to influence the 2016 Philippine elections so that Duterte would be president”.

An enraged Duterte responded by mocking Del Rosario, ranting he would not only sue the former minister, but also “pour coffee on your face”. He has yet to make good on either threat.

Undaunted, Del Rosario issued a statement on November 15 warning that “the Filipino people cannot afford to elect another set of candidates beholden to China”.

“Another six years led by Manchurian candidates would be enough to give away our West Philippine Sea to a foreign aggressor,” added Del Rosario, using the term coined by the previous administration to define the country’s exclusive economic zones and maritime waters in the South China Sea.

The former top diplomat also revealed that the information about the Chinese officials bragging that he had attributed to “a most reliable international entity” was actually “based on personal knowledge from a source in The New York Times”.

Analyst De Castro said he had heard a version of Del Rosario’s claim from other sources as early as 2016, when he visited a research institute in Washington. The word going around then, he recalled, was that “China had gotten Duterte for cheap … they got him for so cheap”.

Duterte said China pledged billions to the Philippines. Where is it?

Rommel Jude Ong, a professor at the Ateneo de Manila University’s school of government, said Beijing would prefer a presidential candidate inclined to “weaken” Manila’s claims on the South China Sea and its alliance with the US.

China would also want someone who would grant it “access to Philippine natural resources such as oil and nickel”, said Ong, a retired Philippine Navy rear-admiral.

Locsin also warned “that a public vessel is covered by the Philippines-United States Mutual Defence Treaty”.

Chester Cabalza, president of the International Development and Security Cooperation research institute, said a pro-Beijing president would “continuously downgrade and disrupt our country’s West Philippine Sea narratives and trumpet defeatism on the importance of the [maritime] arbitral decision”.

Manila refers to the territory it claims in the disputed South China Sea as the West Philippine Sea. Beijing claims almost the entire South China Sea and has built military outposts on several reefs, while Vietnam and the Philippines have done the same, to a lesser extent.

Cabalza said that a “Manchurian candidate” leader would claim to maintain an “independent foreign policy” but “push for preferential treatment for China”.

The chosen one

Ninety-seven candidates have filed to run for the presidency, but when the election commission prunes the list by mid-December, rejecting nuisance candidates and those not capable of running a national campaign, there will probably be seven left.

According to De Castro, the candidates who lean towards China will be those who use “buzz words” such as “setting aside the arbitral ruling” and “joint development”.

On Beijing’s part, Cabalza, a fellow of the People’s Liberation Army College of Defence Studies at the National Defence University in Beijing, said that the favoured candidate could expect “warm economic pledges”.

“There will [also] be promises that Beijing will protect its presidential bet, [making sure] the candidate would finish his or her term of office,” he predicted.

US military, China’s economy: Philippines’ VFA U-turn plays it both ways

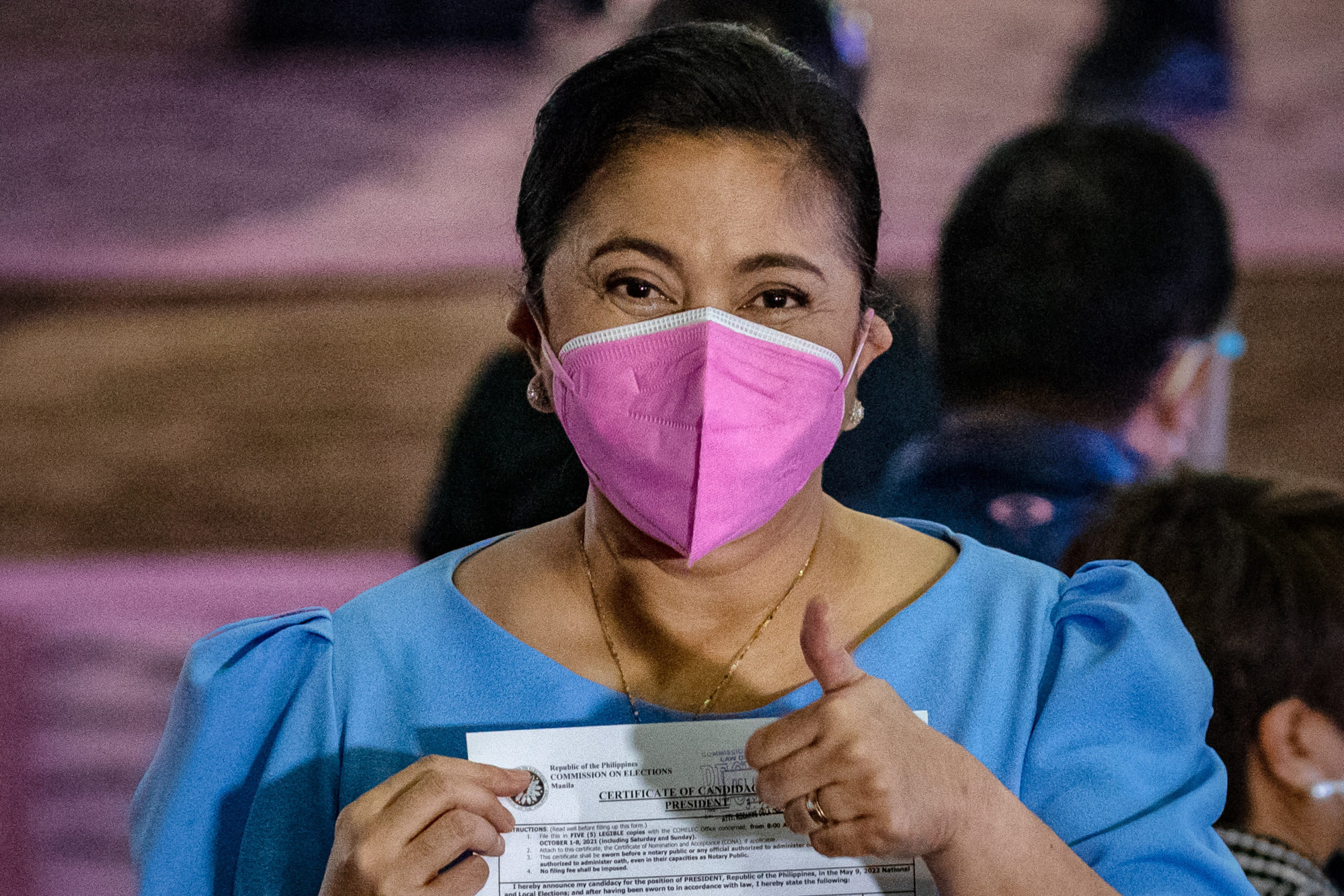

Robredo will have few fans in Beijing. She has already made clear she will assert the international court’s arbitral ruling and has accused Duterte of favouring China.

Senator Go, Duterte’s right hand man, could expect some support from China, but most analysts believe Beijing’s most favoured candidate is Marcos Jnr.

Marcos did not finish college, served without distinction as a congressman and senator, and has been convicted for tax evasion, but he has a pedigree that matters to Beijing thanks to his father’s establishment of diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China.

Lucio Blanco Pitlo III, research fellow at the Asia-Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation and lecturer at the Chinese Studies Programme at Ateneo de Manila University, said that “as his father was instrumental in establishing formal diplomatic ties between Manila and Beijing, it is natural for China to accord respect to the son”.

On October 20, the Chinese embassy invited Marcos as a “guest of honour” in the opening of a photo wall, which featured a picture of his father. Photos showed the guest and the ambassador each seated on large chairs under their countries’ flags, as if it were a state event – although Marcos is a private individual.

The Marcoses have an axe to grind, they felt the US did not support them

Writing about the event on Facebook, ambassador Huang Xilian purred about the “great honour” of meeting the presidential aspirant and his family.

“While [we] always cherish and honour old friends, we hope that more and more people from our two countries will be committed to deepening our partnership and cooperation … Together, we are opening up a brighter future!”

To former minister Del Rosario, there was nothing coincidental about the date of the event. In his statement, he pointed out how Marcos’ visit to the embassy took place around the time he filed his certificate of candidacy.

Rommel Banlaoi, director of the Centre for Intelligence and National Security Studies, said: “It’s obvious … that was a strong message [that] China is comfortable with a Marcos presidency.”

Banlaoi said he had heard the Marcos campaign was working to formulate a foreign policy agenda that would make China “welcome a Marcos presidency”.

For Ong, the embassy function could be “a signal to domestic political actors and maybe to Duterte – that Marcos Jnr is their preferred candidate”.

Another plus for Beijing might be that, as De Castro said, “Bongbong Marcos is very anti-American, he and his family still hold grudges against the Americans”.

When a “People Power” uprising flared against the elder Marcos in 1986, the US withdrew its support of him, instead recognising the government of Corazon Aquino. Marcos and his family fled to Honolulu aboard a US military aircraft.

Is Duterte’s cocaine claim sign of deeper feud with Marcos family?

According to Banlaoi, “the Marcoses have an axe to grind, they felt the US did not support them, and that it even facilitated People Power”.

Asked how Chinese support for its preferred candidate would manifest itself, Ong said it could take the same form that had been seen in other countries: funding and trolls.

He added that efforts would be made to “establish links or cultivate relations with the dominant political party or party in power” and China’s favoured candidate could expect “illicit campaign financing” as well as “disinformation in favour of the candidate, or directed against other contenders”.

Online, Chinese netizens appear to have been fascinated by the dynastic element of the election, with Marcos Jnr’s running mate being none other than Sara Duterte-Carpio, the daughter of Rodrigo Duterte (who apparently is less than pleased with Sara’s decision to run as vice-president under Marcos, rather than aiming for the top job).

On the microblogging site Weibo, many Chinese have expressed backing for Marcos Jnr on the grounds that neither he nor his father had a record of “anti-Chinese” sentiments. Some too have openly wondered whether the new president will be as friendly towards China as Duterte was, or whether he or she might take a more aggressive posture on the South China Sea, like the former president Benigno Aquino III.

America (was) first

Foreign attempts to support and install a biddable leader are nothing new in Philippine history, but until 2016 all the attempts came from only one party – the US.

It was the only superpower that actively intervened in Philippine affairs, its policy determined by the fact that during the Cold War, the two largest American overseas military bases in the world were both in the Philippines. Washington’s objective in the Philippines was to make sure there was a friendly, stable and staunchly anti-communist leader in Manila that wouldn’t kick out or endanger the bases.

In his memoirs written in the 1970s, Joseph Smith, a CIA covert action specialist, recounted how in 1954 American public relations specialists, advisers, covert operatives and propagandists built up the reformist image of a young and charismatic Ramon Magsaysay and steered him into power.

As a president, Magsaysay was so pro-American, he kept his psychological warfare adviser, US Air Force Col Edward Lansdale, constantly by his side, literally looking over his shoulder.

Unfortunately, the president died in a plane crash in 1957, the last year of his term. Smith recalled that despite being told by their division chief to “find another Magsaysay” the CIA never managed to attain that same degree of access and control of a Philippine president.

It is not unwise for presidential candidates to court China

When the Cold War ended, the bases were closed, American forces pulled out and the US interest in the Philippines waned.

Now with the issue of the South China Sea simmering, that interest is back. Ong pointed out, “the [Americans] have much to gain or lose strategically, by now they have learned their lesson with Duterte. Hopefully they will craft a more nuanced policy towards the Philippines based on the two countries’ interests, and not the US alone”.

De Castro, who specialises in Philippine-American relations, said that “yes the US might be interested in the election. But I don’t think they would play a very active role, unlike China. There are already certain constraints such as haunting memories of the Cold War”.

He added: “I don’t think they would intervene unless there is another candidate like Duterte.”

De Castro didn’t say what might happen then.

Cabalza said “the US can offer and will lure [the Philippine] foreign affairs and defence sectors to align with its strategies as Washington helps modernise the Philippine armed forces and improves institution building in the next administration”.

Misdirection

Anxieties over a pro-Beijing Manchurian candidate have dominated discussions to the point that few analysts are discussing the likelihood of American interference.

Ong said while a candidate preferred by Beijing would have to deal with an anti-China attitude among the public, they could refocus attention on a campaign promising jobs, a better pandemic response and stamping out corruption in government.

Pitlo said China presented both a challenge and opportunity to any candidate but he cautioned: “Even as being associated with China carries risks, being overly adversarial to Beijing is also unhealthy as this may affect burgeoning economic ties.”

He pointed out that “China is the country’s largest trade partner, second largest investor, third largest export market, fastest growing inbound tourism market pre-pandemic and an emerging player in the country’s infrastructure. Thus it is not unwise for presidential candidates to court China, while keeping a principled stand on the West Philippine Sea”.

In comments given to the nationalist Chinese tabloid Global Times in September, Chen Xiangmiao, an assistant research fellow at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, warned of economic consequences if the next leader was too pro-American.

“If the new leader goes too far towards the US, there could be a huge loss of investment from China, something the Philippines cannot afford at the moment,” he said.

For their part, the two superpowers will have to deal with the twists and turns of Philippine politics currently entering a new level of teledrama surprises, in which nothing can be taken for granted. Most analysts assumed the Dutertes and Marcoses would be allies, but recent comments from the current president have suggested they might be opposed to each other.

In an article published on his station’s webiste, Liu Heping, a Shenzhen Satellite TV commentator, pointed out that when Duterte was elected many expected him to break with the country’s political traditions, but in recent weeks he had undermined such hopes by what appeared to be attempts to cling to power – by encouraging his daughter’s ambitions (at least, before she joined Marcos’ card) and with his last-gasp application to run as a senator, submitted just hours before deadline. Liu said Duterte had probably decided to run for the senate as he was afraid of being pursued by political opponents after stepping down as president – the International Criminal Court is investigating his infamous war on drugs for suspected crimes against humanity – and this might give him some measure of immunity.

Indeed, it seems as if every week there are new surprises. As Dai Fan, director of the Centre for Philippine Studies at Jinan University in Guangzhou, pointed out in an interview with Shanghai website The Paper, there are likely to be many more uncertainties in the half a year that remains before the vote on May 9.

In a November 16 interview via Zoom, Cabalza told state-owned cable TV news service CGTN Asia Today that Beijing should “brace” itself for a possible situation in which the opposition candidate Leni Robredo – thought to be its least-favoured contender – wins the presidency while Marcos’ running mate Sara Duterte-Carpio wins the vice-presidency.

For candidates, campaigning under the scrutiny of two superpowers will require a balancing act.

Said De Castro: “Two great powers are playing chess and we are the pawns.”