Duterte, Marcos, Estrada, Cayetano: Pacquiao can’t beat the Philippines’ political dynasties, but he can join them

- In the Philippines’ free and open elections, it’s easy to vote a political family out of power – vote another one in. Welcome to the ‘world capital’ of political dynasties

- The Duterte and Pacquiao clans are just the latest big-hitters in a tradition that goes back generations and bestows great benefits. As one observer puts it, ‘if politicians were listed on the stock exchange, they’d put most blue chips to shame’

When Manila mayor Isko Moreno announced on September 22 that he was running for president next year, he went out of his way to stress one thing: he did not belong to a political family.

Moreno, 46, a former actor whose real name is Francisco Domagoso, said: “I don’t belong to a large clan. I am neither son nor daughter of a president. You won’t find the faces of my impoverished ancestors on peso bills. No avenues are named after them, not even a side street or a waiting shed.”

He was telling voters they need not worry that he would contribute to the country’s biggest political curse: self-serving clans that monopolise elective positions and treat them as if they are heirlooms.

Manila’s celebrity mayor Isko Moreno to run for president

Members of these clans occupy positions at every level, from national down to the village level. No matter who wins or loses an election, the winner is usually from one dynasty or another.

Ronald Mendoza, dean of the Ateneo School of Government, said that as of 2019, 80 per cent of governors, 67 per cent of vice-governors, 66 per cent of congressmen and 53 per cent of mayors belonged to political dynasties.

Mendoza defined a political dynasty as a family that had at least two members in public office, and distinguished between a “thin” dynasty – in which members serve in succession – and a “fat” one, in which relatives occupy various positions simultaneously.

The entrenched families are a blight on the country’s economic and political development. Mendoza said studies showed that political dynasties were “associated with underdevelopment, bad governance, and in some cases, extreme degrees of impunity”.

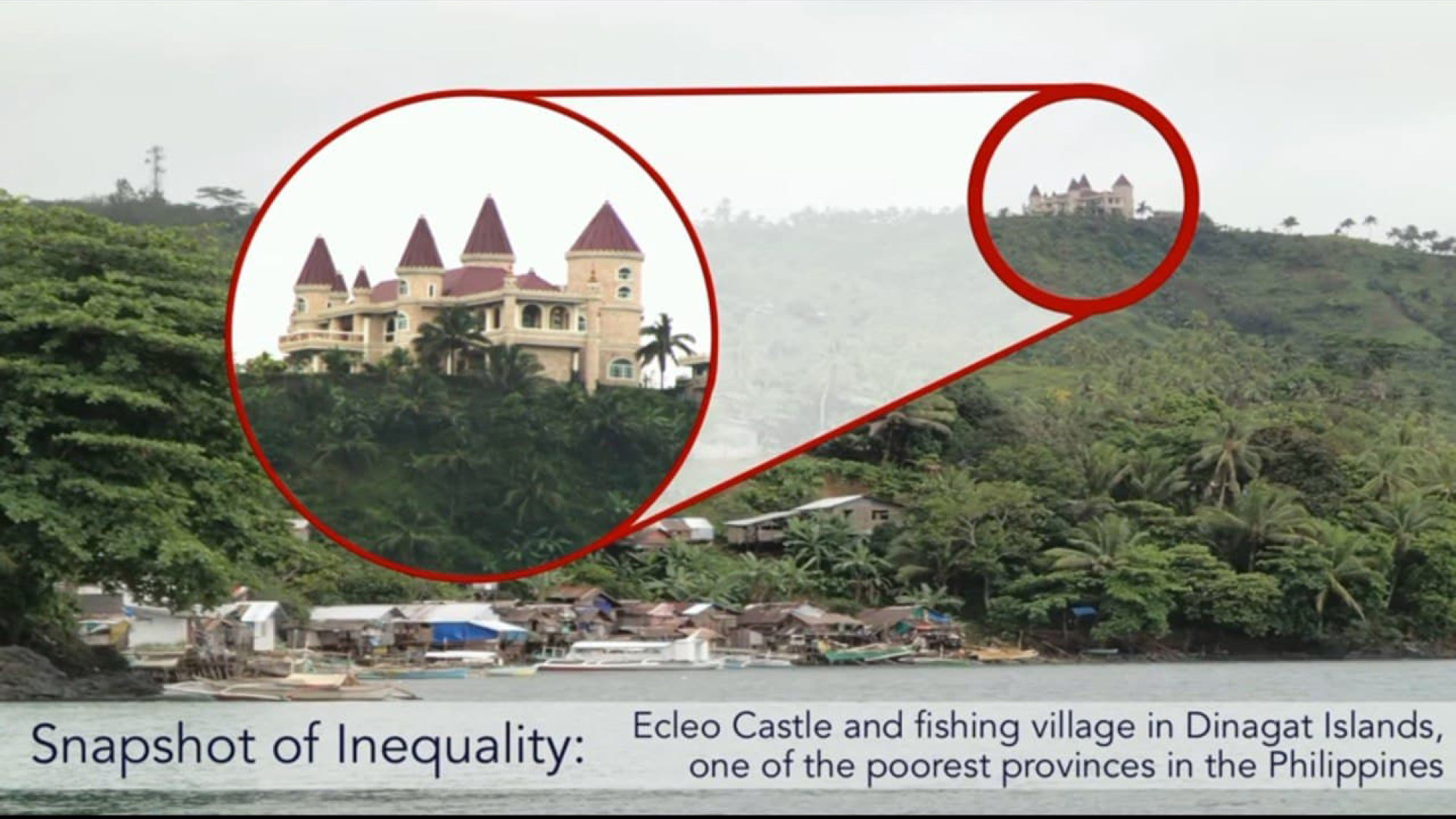

Families that monopolise power can become so wealthy, they live like royalty. In the poverty-stricken Dinagat Islands province in southern Philippines, the Ecleo clan lords over the inhabitants atop a hill in a bizarre, garish and gaudy structure that residents call the “white castle”.

When Moreno ran for mayor and won in 2019, the man he displaced was one of the country’s archetypal dynasts: disgraced ex-president Joseph “Erap” Estrada.

An action star who won his first elective post in 1969, Estrada started as mayor, moved on to senator, vice-president, president, and then back to being mayor. During that 50-year trajectory, his wife, son, common-law spouse and his son by her, all ran and won positions in national and local levels.

Though Estrada’s career survived his being chased out of the presidency in 2001, and then being tried and convicted for plunder (he was later pardoned), his fat dynasty’s political fortunes crashed in national and local midterm elections in 2019, when not one member who ran for office won.

The list in that debacle included the patriarch himself, two sons, one daughter, a nephew and a granddaughter. It didn’t help House Estrada that two of his sons, half-brothers JV Ejercito and Jinggoy, went head to head competing for a seat in the senate.

While dynasties like Estrada’s might have faded, they are readily replaced by others.

“If you consider it an elite competition, there are always new elites vying for power,” Mendoza said.

It is almost a truism that the first thing Filipinos do when they are elected to public office is to make sure the position stays in the family.

Mendoza pointed out that when the murderous dictator Ferdinand Marcos was overthrown, “many of the anti-Marcos leaders ran for office but eventually set up their own dynasties; they started to play the same game rather than reform the system”.

Family affair

A dynasty typically starts when one member wins a position, which is then handed to siblings or children while the original occupant seeks other offices. As more relatives are recruited into the enterprise, the branches of the family tree coil tightly around the ballot box.

In the country’s political culture, families trump political parties, which are just convenient platforms cobbled together to launch, or sustain, dynasty members. Despite half-hearted attempts to legislate against dynasties, the clans are as dominant as ever.

“It’s not getting any better, in fact it’s getting worse,” said Teddy Casiño, who was a congressman for Bayan Muna party-list from 2004 to 2013 and is currently its spokesman.

As Duterte exits Philippine election, will daughter Sara run for president?

He said it had become “commonplace and acceptable” to see families divvy up offices in ways that might have been considered “scandalous” three decades ago.

“A husband and wife in positions or a father who is governor and his son as vice-governor … [political dynasties] have managed to strengthen their hold on power.”

According to Mendoza, studies show “the real tendency is to consolidate power at the local level, and to field multiple candidates”.

He said there were “many examples of [family members making up] mayor-vice-mayor tandems: mother and daughter, father and son”.

The reason was that “the vice-mayor is always the bigger threat to the mayor, so it’s better to run with a family member”.

Duterte spokesman who mocked the UN now hopes they’ll give him a job

The Cayetano clan had their own musical chairs: Alan Peter, formerly a senator and then Duterte’s foreign affairs secretary, won a seat in congress as did his wife Lani, who took over the position of sister Pia, who returned to the senate. His brother Lino, formerly a congressman, became mayor of Taguig City.

Meanwhile, the family of Ferdinand Marcos – the president who declared martial law to set up a murderous 14-year dictatorship – proved that a bloody and sordid past was not a hindrance in elections: the dictator’s daughter Imee won a senate seat, giving up governorship of Ilocos Norte, a post which her son Matthew handily won.

The dynasty founded by billionaire Manny Villar also advanced, with wife Cynthia reelected to the senate and daughter Camille winning a seat in congress.

For next year’s election, Mendoza said there were “a number of very powerful clans already making noises – the Cayetanos, Pacquiaos, Marcoses, Revillas and the Remullas from Cavite [province], the Binays in Makati City, Gatchalians here in Valenzuela City”.

Don’t mention it

Dynasts invariably bristle when the topic of their clan’s growth and power comes up. In 2019, news site Rappler reported Alan Peter Cayetano asserting his family was not a political dynasty and claiming there were no political dynasties in the country.

“There are no dynasties in the Philippines because we have free and open elections,” he said. “The concept of a dynasty, or being an aristocrat, is that you can replace your parent because you have the same name. In the Philippines, you have to earn it.”

Pacquiao has also repeatedly denied he’s building a dynasty. In 2019, when asked about his position on an anti-dynasty bill, he replied that “everyone has an opinion about that but for me, it’s the people who will choose. After all, we are a democracy”. He said that “if someone is elected by the people, chosen by the people, because of their service, why not?”.

Senator Cynthia Villar had the most blunt outlook: she told reporters in 2018 that dynasties were “here to stay, what is important is that it is a good dynasty”.

She said a political dynasty was “something that is natural … what is important is that people learn to elect good public officials”.

Congress is a club of political dynasties, they all know each other ... It’s not just an old boys’ club, it’s a family affair

Dynasts are fond of depicting themselves as hardworking public servants, but fail to emphasise their perks.

Mendoza noted how “some dynastic legislators in both houses have experienced phenomenal growth in their wealth while in office”.

He mentioned, without identifying, one senator whose wealth increased 500 million pesos (US$9.8 million) in just three years. His wife, also a senator, saw hers increase by 1.9 billion pesos in just six years.

He said that when researchers tracked the statements of assets and liabilities of some dynastic congressmen, they found “impressive growth rates in wealth, ranging from almost 200 to well over 300 per cent in over three years”.

“If these congressmen were listed on the Philippine Stock Exchange they would put most blue chip stocks to shame,” Mendoza said.

Wealth and political patronage contribute to the staying power and growth of dynasties.

Casiño said that “poor people tend to look for patrons, chronic and widespread poverty allows these economically powerful families to play the role. The substance of the relationship is financial and economic and it takes so little to establish it”.

He recalled how, when he was a party-list representative, all congressmen were allotted funds to give a one-time aid payment of 7,000 pesos to each student for training courses. He noticed that congressmen from political dynasties halved that amount per student so they could have double the number of “scholars”.

“The point is, if you are a poor family and receive a scholarship, your gratitude will be immense. The poorer you are the bigger your utang na loob [deep gratitude].”

Mendoza described the relationship between dynastic politicians and their constituents as “a low level situation, where [the constituents’] ambitions have been basically reduced and they are satisfied with it”.

“We are missing political party reforms, campaign reforms,” he said.

Pacquiao files bid for presidency as violence looms over Philippine polls

Casiño, who said he was running as a party-list representative in next year’s election, described how during his first week in congress, he sat at the south lounge with the late Roilo Golez, a long-time congressman.

“He described everyone who entered the lounge, and it was, ‘he’s the father of, or the uncle of … it was all spouses, siblings, children.

“That’s when I realised congress is a club of political dynasties, they all know each other, they’re that entrenched,” he said. “It’s not just an old boys’ club, it’s a family affair.”