The US Peace Corps, a fixture in Asia, is in Vietnam at last – a sign Hanoi-Washington ties are on the upswing?

- Seen as competing with China’s Confucius Institutes, the decades-old American aid programme is finally launching in Vietnam after 17 years of negotiations

- The Peace Corps’ presence in China was axed last summer after 26 years, amid US-China conflict over trade, technology, and civil liberties

Volunteering with the US-government-funded programme is something of a tradition in the 39-year-old American’s family, with no fewer than five of his relatives having served as volunteers in Central and South America, as well as in Europe.

“I love helping people learn and I’m very interested in delving into a cultural world that I haven’t experienced much in my eight years here,” said Herman, who currently works full-time as an English teacher at a factory in the southern manufacturing hub of Binh Duong.

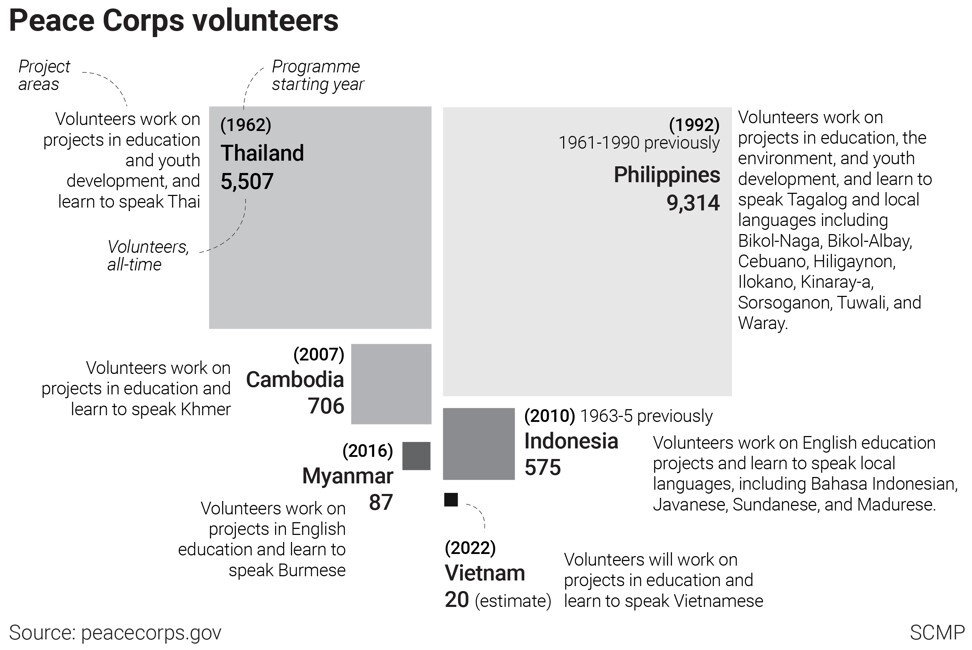

Founded in 1961 by US President John F. Kennedy, the Peace Corps – an artefact of the Cold War that was meant to spread goodwill towards the West – has never before operated in Vietnam. In contrast, the humanitarian group has had a presence in Asean member states such as Cambodia, Indonesia, Myanmar and Thailand for years – with the Philippines hosting the most US volunteers in all.

“It is intriguing to note that while the US-China rivalry is taking on stronger ideological overtones, [the] US-Vietnam relationship continues its upwards trend regardless of ideology,” said Hoang Thi Ha, a fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute’s Asean Studies Centre in Singapore.

“If anything, this suggests the diverging trajectories of US-China and US-Vietnam relations in the years ahead,” she said, adding that the opening of a Peace Corps office in Hanoi signified growing trust between the US and Vietnam, anchored in the assurance of respect for each other’s political systems.

It shows that the relationship between the two countries has been raised to a new level

Yet the launch of Peace Corps Vietnam still took 17 years to negotiate. When asked why, Kate Becker, Vietnam country director for the programme, said given the “complicated history” between the US and Vietnam, establishing trust was not a simple process.

“Building an understanding of each other’s cultures and living day to day as a neighbour, colleague and friend, taking meals together … This people-to-people aspect of service is the essence of the Peace Corps,’’ she said.

Dr Pham Quang Minh, a former dean of the University of Social Sciences and Humanities in Hanoi, said Cold War thinking and concerns about the influence of American culture could partly explain Vietnam’s hesitation, if any, in hosting the Peace Corps.

“There may also be concerns about China because China certainly does not want Vietnam to be close with the US, although Vietnam does not like and even opposes China, but also does not dare to express it openly,” said the foreign-policy specialist.

The institutes, widely regarded as a tool for China to promote its image and project soft power abroad, were first established in 2004 and are now in some 154 countries, many of which host multiple institutes.

Vietnam, however, has only one: at Hanoi University, which Minh said “almost no one knows about and its activities do not stand out”.

Culture shock

The Peace Corps’ Vietnam programme aims to support the country’s “national priority of English proficiency for its secondary school students and emerging workforce, as well as strengthening teachers’ English proficiency and capacity to teach English”, according to its website.

Prospective recruits have been told that Vietnamese officials will “likely be curious about your work, language development, and community integration” and were warned not to expect online privacy as “the government of Vietnam routinely monitors all social media”.

Luis Valadez, director of programming and training for Peace Corps Vietnam, said suitable volunteers would have to be culturally open-minded and understanding, as they would not only be tasked with integrating into the local culture during their service but be expected to act as a cultural bridge upon their return to the US.

“Therefore, it is important that our volunteers do not approach any element of their service with the attitude of being an ‘expert’ or as if they already know everything,’’ he said, adding that the first cohort of up to 20 volunteers were expected to begin working in schools around Hanoi next year, with 20 more slated to start in 2023.

“Volunteers will live in the same communities where they work with local host families and will be required to be fully vaccinated against Covid-19,” Valadez said.

Since its inception, more than 241,000 Peace Corps volunteers – mostly female, with an average age of 27 – have been sent to some 143 nations. Africa has received the most volunteers at 45 per cent of the total, while only about 13 per cent have served in Asia. Most projects focus on education, health and youth development.

The agency received US$410.5 million in funding from Congress last year, its 2020 financial report said, with another US$88 million spent on bringing volunteers, trainees and other staff home amid the pandemic. Its budget accounts for around 1 per cent of the US foreign operations budget, according to its website, and it can also accept donations from the public.

The absence of any Peace Corps volunteers serving abroad because of the pandemic “does untold damage to our strong community-based worldwide presence and the United States’ image abroad”, the letter said.

Despite being generally well-liked, the Peace Corps has long had to contend with suspicions that it is a front for US intelligence agencies, as well as charges that it is merely an extension of what has been termed the “white saviour complex”.

In April, USA Today published an investigation on female volunteers who had been sexually assaulted during their service with the Peace Corps, in a further blow to the agency’s reputation.

However, the launch of Peace Corps Vietnam represents a symbolic upgrade of US-Vietnam relations, according to foreign-policy specialist Minh – despite the two not yet officially being “strategic partners”.

“It shows that the relationship between the two countries has been raised to a new level because before the Peace Corps was considered an ‘imperial tool’, an intelligence organisation of the CIA,” he said.

“The Peace Corps will be the bridge between the two sides: making Vietnam understand the US better and the US also understand Vietnam better.”