Explainer | As China-India border stand-off drags into winter, nomadic herders become collateral damage

- Months into the deadly face-off, communities which rear yaks and goats in the area have not been able to pass to the Chinese side, threatening an ancient way of life

- Out of desperation, they have been forced to migrate towards more urban settlements and work as petty labourers

“I am not accustomed to work as a coolie,” he said, despairingly. “Carrying these heavy cartons aches my back but I will have to do it for feeding my family.”

By November in any other year, the 46-year-old would not be in Leh but with his family herding yaks and goats at high altitudes in search of grazing pastures.

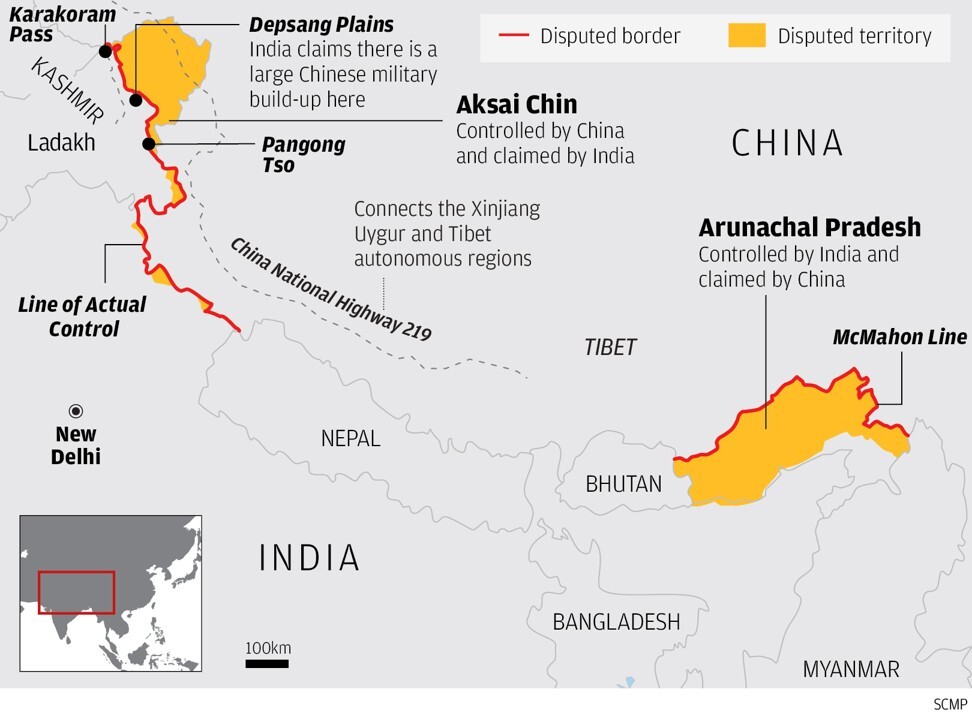

Every winter, when the temperature drops to minus 50 degrees Celsius, the nomadic herders on the Indian side of Pangong Lake, which is claimed by both India and China, wait for it to freeze. At the first opportunity, they pass over it to higher altitudes with their livestock in search of greener pastures.

China-India border dispute: Delhi ‘expects Beijing to stand down first’

Jinpa was in Chushul, a village about 200km from Leh, when the Chinese troops descended on the region this year, but said this was nothing new.

“It is a regular affair,” he said. “They come into our area every year but also retreat back as soon as the winter arrives.”

As a precautionary measure, though, by mid-May Jinpa had decided to descend back to Leh and wait for the Chinese to leave the area.

For many locals, the fighting revived memories of the 1962 Sino-Indian war, during which China consolidated its control over Aksai Chin, a 38,000 square kilometre territory northeast of Ladakh that India claims as its own.

Jinpa had only heard about the difficulties the war brought to local nomads, with much of the fighting occurring in the nomadic hinterlands of Ladakh. But today, with most of the grazing grounds having become inaccessible because of the military stand-off, the loss seems very personal.

These sentiments were echoed by the former chairman of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council, Rigzin Spalbar, who has watched his community’s grazing lands disappear before his eyes.

“Several of our green pastures in Demchok and Chumur which served as a lifeline for the herders have been taken over by the Chinese. Out of desperation, these herders have been forced to migrate towards more urban settlements and work as petty labourers,” he lamented.

“These people don’t know anything beyond rearing” their animals, he said. “What we are seeing is simply a mass exodus of nomads from their habitations.”

Having watched the Chinese closely over the years, Spalbar points to a pattern that its troops follow.

“China’s modus operandi is very simple,” he said. “They first send their nomads across the border to gauge the Indian response. And when they see no real will from the Indian troops to push back the invading herders, then the [People’s Liberation Army] follows, sometimes camping for a few months and sometimes settling permanently.”

The kids aren’t all right: India-China border row killing pashmina goats

Although Spalbar has sympathy for the herders, he is also critical of the Indian government, which he said had lied from time to time about the Chinese incursions because it did not want to face the fact that a more powerful and aggressive military was nibbling away at its territory.

But Spalbar, who knows the terrain of Ladakh like the back of his hand, repudiates such statements as false and misleading. He alleges that the Chinese have been chipping away at Indian land for years, but that successive governments in New Delhi have continuously ignored their actions.

“This is our land and we are well within our rights to reclaim it even by force if required,” he said.

Namgyal Durbuk, a former local councillor in the region, agreed, adding that China’s present incursion was unprecedented.

“This time around they have come a long way inside. Earlier our herders used to go to all the eight fingers but now the experts and satellite imagery say the Chinese are in control of at least four of them,” he said, referring to the eight finger-like ridges overlooking Pangong Lake, each of which is variously claimed by India or China. China, for example, has set up a military base near Finger 5, on the north bank of Pangong Lake, completely cutting off the Indian Army.

‘We’re finally fighting our enemy’: Tibetan soldier killed on China border

“For years, the Chinese have been eating away our grazing lands. Still, our own army and government chose to turn a blind eye fearing the risk of irking them,” he added.

Despite the periodic optimism that a resolution to the border stand-off is in sight, Indian news reports have suggested China has not only dug its heels in Ladakh, but has brought in more troops and built air-defence systems, including missile launchers, in the region.

South Asia experts such as Michael Kugelman of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington do not believe the stand-off will end soon, and that even if it does, the dispute that led to the stand-off will remain.

“You could have a return to some sort of status quo ante but it is only a matter of time before you have another stand-off, which could be even more serious than the current one,” he said.

Detached from the world of high politics, Jinpa is more worried about his livelihood. His yaks and prized Ladakh Pashmina goats have grown thinner. “This is all that I have,” he said, pointing to the herd. “If they will die of hunger, so will I.”

Jinpa owns a half-dozen of the goats, which yield some of the world’s finest – and most coveted – feather-light cashmere wool. Most of this wool is woven into exquisite shawls in the adjacent and equally troubled Kashmir valley, where the pashmina wool industry supports tens of thousands of people.

He and his tribal community produce around 50 tons of the wool every year, which can be sold for up to US$50 per kilogram – enough to support a single family’s yearly expenses. But the denial of access to grazing lands has led to a higher mortality rate among the Ladakh Pashmina goats.

“This year, we completely lost the breeding season for our goats. Almost a quarter of the newborns perished because large herds were pushed out into the cold from the grazing lands,” Jinpa explained. “If another breeding cycle is lost, we are surely doomed.”

He added, with a sigh: “When two elephants fight, it is always the grass that suffers.”