Ambani, Tata, Hinduja: how India’s family-run business empires battle over their billions

- From Mukesh Ambani’s falling-out with his brother Anil to the recently settled Tata dispute, India is no stranger to rancorous legal battles between family members

- A lack of succession planning is often to blame, observers say, in a country that ranks third globally for family-owned businesses

Last month saw the culmination of one of India’s ugliest courtroom dramas that pitted billionaire industrialist Ratan Tata, 83, against his relative and former protégé Cyrus Mistry, the erstwhile executive chairman of the US$106 billion salt-to-software Tata group.

Mistry was ousted from his post in 2016 after a four-year stint – but instead of exiting quietly, the 52-year-old decided to drag his mentor to court, claiming unfair dismissal. The Supreme Court, however, backed the removal of Mistry and ruled last month that his ousting for lacklustre performance was legal.

The verdict created national news, as millions of Indians sat glued to their television sets following the twists and turns of the Tata vs Mistry saga, which dragged on for years. Analysts weighed in with their opinions while most observers simply heaved a sigh of relief once the dispute, which had brought unwanted global attention to India Inc, came to a close.

Family feuds between some of India’s other illustrious business families have been no less rancorous. The country ranks third globally for family-owned businesses, with 111 companies that had a total market capitalisation of US$839 billion in 2018, according to Credit Suisse Research Institute.

Is Mukesh Ambani seeking to share his US$200 billion empire with his children?

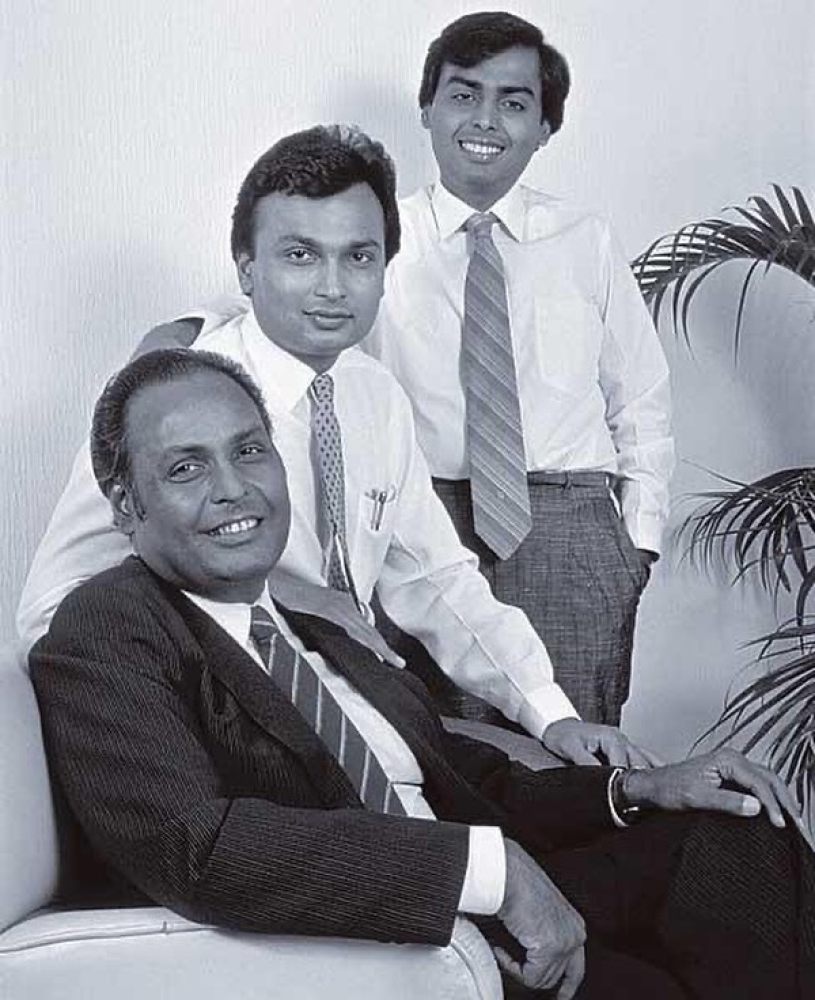

Perhaps the most high profile case was that of India’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani – net worth US$91 billion as managing director of Reliance Industries – and his younger brother Anil, chairman of the Reliance ADA Group with a net worth of US$79 million.

After the brothers’ father Dhirubhai Ambani – founder of the Reliance business empire – died without a will in 2002, Mukesh as elder sibling was anointed chairman and managing director of Reliance Industries while Anil took over the reins of vice-chairman. But the two clashed repeatedly over the next four years until their mother intervened to broker a truce in 2006. The Reliance empire was split, with Mukesh inheriting the core Reliance Industries and Anil taking over its telecoms, power, entertainment and financial services divisions.

In the years since that equal division of assets, however, the brothers’ fortunes have followed quite different trajectories. Mukesh Ambani is currently the eighth richest person in the world with a fortune of US$83 billion, according to the Hurun Global Rich List 2021.

His brother, meanwhile – once among the world’s wealthiest – has become buried under crippling debt from his failed companies. Last year, Anil’s lawyers argued in a British court that his net worth was zero, though much doubt has been cast on the claim since. The case was brought by three Chinese banks that say the tycoon owes them US$680 million in dues after an alleged breach of personal guarantee on a debt-refinancing loan of around US$925 million.

Sibling rivalry also lies at the heart of the Britain-headquartered Hinduja group’s corporate and legal hassles in recent years. The US$11 billion empire straddling 38 countries is run by four Indian brothers – Srichand, Gopichand, Prakash and Ashok – and has stakes in the automotive, financial services, IT, media, infrastructure, energy, chemicals and health care sectors.

In 2014, the brothers signed a letter declaring that assets held by one belong to all, and that each member would appoint the others as his executors. But 84-year-old Srichand, the group’s patriarch, now wants that letter declared null and void and the family’s assets divided according to his and his daughter Vinoo’s wishes – a prospect the others find unappealing. A decision on the matter is set to be made by a London court at a later date.

Deep pockets, big hearts? India’s 5 most generous billionaires of 2020

Another family legal battle consumed the close-knit Bajaj group, helmed by 82-year-old Rahul Bajaj, from 2002 after some of his various brothers, cousins and their children decided they wanted their piece of the pie.

Squabbling over the future of the group – one of India’s oldest and largest conglomerates with interests spanning vehicles, insurance, sugar, steel, and household electrical appliances – continued until 2006 when the matter was finally resolved with help from the government-run Company Law Board.

According to legal specialists, much of the wrangling among India’s family-owned enterprises could be avoided with clear succession planning. However, a 2018 report from Edelweiss Private Wealth Management, one of India’s largest wealth management firms, and Campden Family Connect – a joint venture between Britain-based Campden Wealth and India-based Patni Group that manages private wealth – found only 19 per cent of 78 Indian families with an average net worth of US$645 million had formally agreed upon such arrangements.

India’s Ambani dethroned by Chinese billionaire: a ‘matter of national shame’?

Family friction can also be avoided by bolstering the role of independent board members or getting independent advisers from outside the family, observers say.

Bringing more women into boardrooms could also help avoid conflicts, according to activists, who say patriarchal India is bedevilled by an absence of women in the top echelons of business. Only 118 of the top 500 companies listed on the National Stock Exchange of India in 2018 had an independent female board member, according to corporate governance reports filed by companies that year – the latest for which figures were available.

“Traditionally, families tend to ensure that businesses get passed down to the male heirs of the family,” said Mumbai-based corporate lawyer Girish Patnaik. “This creates a dangerous skew which not only harms the company’s growth and inclusiveness, but also deprives talented women of equal opportunities.”