Asian Angle | Why the Philippines should rethink its South China Sea name-and-shame game

- Manila’s transparency strategy to expose Beijing’s transgressions has paid off, to an extent. But it won’t change China’s behaviour

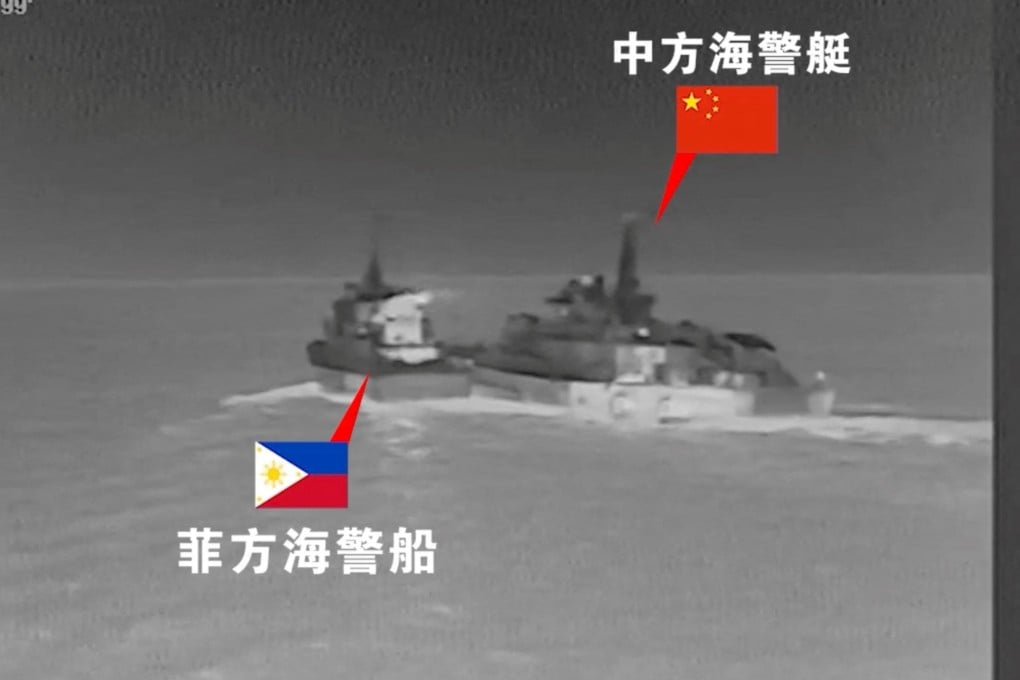

Far from easing tensions, mutual recriminations heightened the temperature in choppy waters. Both sides pandered to their domestic base. Maritime incidents worsened alarmingly, ranging from the use of lasers, dangerous manoeuvres, ship collisions, and water-cannon blasting to a physical scuffle that resulted in injuries to sailors. Flashpoints flared up at the Second Thomas, Scarborough, and Sabina Shoals. Chinese vessels sighted in Philippine waters increased. Beyond the West Philippine Sea, they were also spotted in the Philippine Sea in the east and Basilan and Sibutu Straits in the south. Close calls also occurred in the sky, with People’s Liberation Army aircraft dropping flares in the path of a Philippine Air Force plane patrolling in the vicinity of Scarborough Shoal.

Transparency can be a useful tactic, and Manila is not the first to employ it in the South China Sea. But there is a difference between exposing a rival for exposure’s sake and calculated exposure as diplomatic leverage. The former aims to inflict open-ended maximum reputational cost without creating pathways for de-escalation. The second is more restrained, incident-specific, and opens doors for off-ramps to cool tensions.

At present, activities in the South China Sea would not go unnoticed. Air and sea patrols and commercial satellite solutions can easily reveal reclamation work, militarisation of occupied features, or congregations of vessels. Even the movement of ships that turn off their automatic identification systems at night can be tracked.

Coastal states now have access to more information, which can be leveraged for diplomatic protests or negotiations. Sharing or leaking this information to the public and media has become a useful card to be played sparingly to illustrate a point or elicit a desired reply. Dangling the prospect of using such a card may also have more value than putting it on the table.