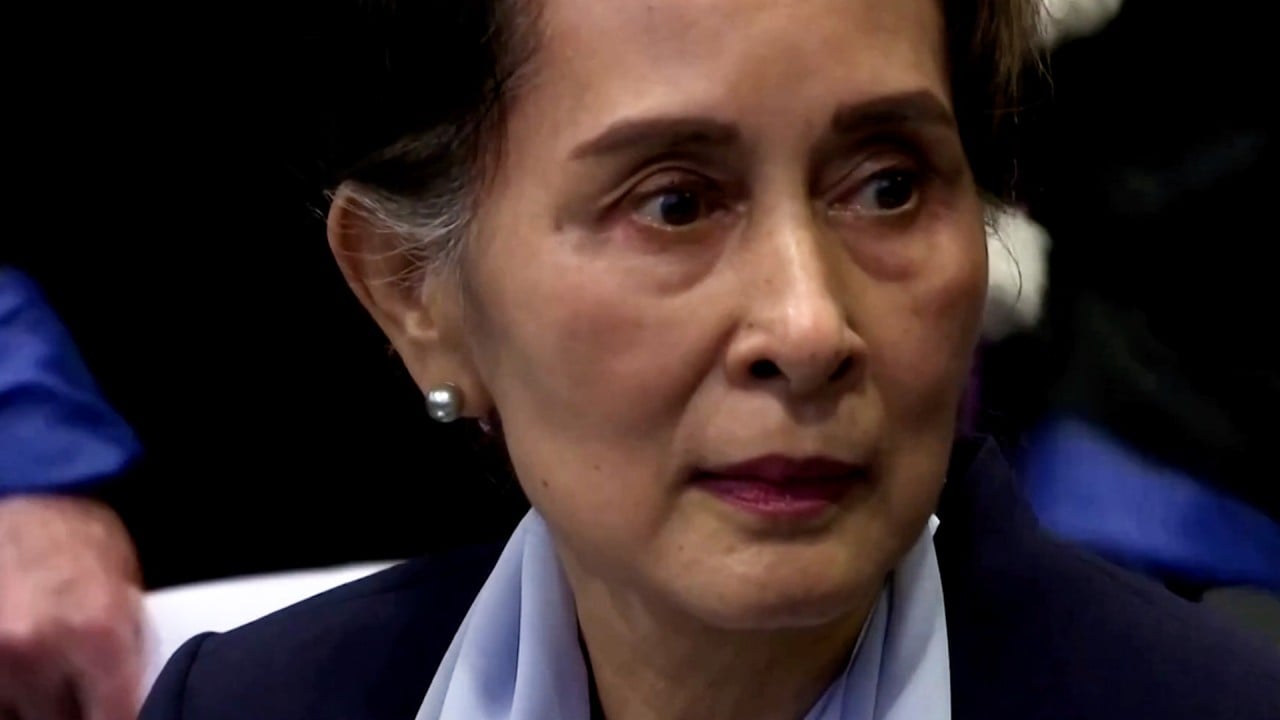

Why Myanmar’s brutal military junta can never defeat Aung San Suu Kyi

- The military – which toppled Suu Kyi, now 78, in a 2021 coup – has reduced her jail term by 6 years, but she still faces over 25 years behind bars

- The gesture and others, like releasing prisoners, is an empty one – and not enough to alter how the regime is viewed on the international stage

But it still leaves Suu Kyi facing a 27-year jail term on bogus charges.

The junta also lopped four years off former president Win Myint’s sentence, and reportedly released more than 7,000 other prisoners.

But we should not be persuaded that the generals have changed their stripes. The junta regularly uses mass amnesties in an attempt to cultivate goodwill at home and abroad. But any prominent figures released in these amnesties should not have been locked up in the first place.

The 2021 coup sparked widespread and ongoing violence, and shredded the military’s last claims to social esteem. This has left Myanmar impoverished, largely friendless, and without any clear plan for a positive future.

Determined resistance

The army’s top decision-makers, currently bunkered down in the capital, Naypyidaw, struggle to maintain control of enough territory to seriously contemplate even a heavily stage-managed nationwide poll.

Under these volatile conditions, people have been voting with their feet by fleeing abroad or taking up arms in a revolutionary mobilisation.

The junta’s leader, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, reportedly told the military-led National Defence and Security Council that elections could not be conducted due to continued fighting in several regions.

The reality for the generals in their fortified compounds is that any poll could further embarrass them – they cannot even reliably rig the national vote.

Myanmar’s partial pardon of Suu Kyi a ‘cynical ploy’ to ease global pressure

Inch by inch, the diminution of central government control raises questions about the country’s future.

Diplomatic efforts to maintain Myanmar’s territorial integrity jostle with the discomfort felt almost everywhere about doing business with a blood-splattered regime.

An unnecessary crisis

It is a precipitous erosion of what was, until the coup, a relatively positive story for most Myanmar people.

Before the military seized power, the most problematic issue was its abuse of the Rohingya, a Muslim ethnic minority in westernmost Myanmar.

Other issues – such as long-standing ethnic grievances and yawning economic inequality – were, at the very least, subject to open debate in the media and sometimes in the country’s 16 regional and national legislatures.

That political and social infrastructure, and the emerging civil society it helped sustain, has now crumbled. It’s been replaced by violence, mistrust, terror and martial chauvinism.

Myanmar’s young talent – banned from universities and bravely disobedient in the face of tanks and bullets – face dismal options: the mountains, the jungle, or the border. Some lie low. Others still seek to fan the revolutionary spark. Many are now in jail, others dead.

The military, of course, blames its opponents for the devastation its coup unleashed. That sad fact hides a tremendous political and cultural miscalculation.

It is unclear whether Myanmar can recover from the army’s self-inflicted wounds. Some speculate the whole system will collapse, making it impossible for power brokers to keep up the increasingly flimsy charade of state power. It has all the ingredients of a failed state.

No way out

The decision to abandon the proposed elections, followed by last week’s amnesty, is hardly a surprise. But it does reveal the fragility of the military system and the paranoia of the men in charge.

It is also further evidence that nobody can trust the junta. Not only has it broken the faith of the Myanmar people, it constantly tests the patience of foreign governments, even those that offer some sympathy for its self-sabotage.

With Suu Kyi – previously detained by the military for almost 15 years – and other senior members of the democratically elected government still locked up, the reality facing the generals is that they will never beat her in any election.

They are still betting that eventually the world – and, most importantly, their near neighbours – will lose interest and allow some type of partial rehabilitation. Maintaining links with China and Russia is a key strategy.

Opinion: Thailand’s Myanmar approach exposes flaws in Asean that other actors may exploit

Still, there is no obvious path to fuller inclusion in Asean while the generals unleash such violence against their own people.

The extension of the state of emergency and postponement of hypothetical elections will further invigorate resistance forces hoping to steadily weaken the army’s grip on power.

A pointless reduction in the jail sentences for Myanmar’s democratically elected leaders is unlikely to quell the fires of opposition now burning across the country.