Malaysians’ regard for the entitlements of office has echoes of ancient China. Anwar Ibrahim spurning official car is like a mandarin riding on horseback

- The Malaysian prime minister says he won’t use the Mercedes-Benz limousine meant for him. This has echoes in the thrift seen under some imperial Chinese rulers

- Depending on their rank, Chinese mandarins travelled by horse and carriage, palanquin or on horseback. To show thrift, high officials would choose the latter

The uncertainty following Malaysia’s general election on November 19, where no single coalition or party won enough seats to form a simple majority in the country’s 222-seat parliament, is no more.

After a string of negotiations between political parties and an intervention by Malaysia’s constitutional monarch, Malaysians now have a unity government, formed by the alliance of several coalitions, and a new prime minister, Anwar Ibrahim.

Even before the new government gets down to the business of running the country, Anwar has shown that he wants a break from the past. While some of the measures that he announced, such as reducing the salaries of ministers and not drawing his prime minister’s pay during his time in office, may be symbolic, they clearly indicate that he wants to bring about a cultural change in the government and civil service.

For a long time, many officials in Malaysia have had an unhealthy relationship with the accoutrements of their office. Titles and honorific addresses, the size of their entourage, their flight and accommodation class when they travel, the make of their official cars – all these have acquired a disproportionate level of importance.

Of course, this phenomenon is not exclusively Malaysian, but it is one that has long been observed in Malaysia. It is therefore heartening to read that Anwar has decided not to use a brand-new Mercedes-Benz S600 limousine, which had been purchased before he became prime minister, as his official car. He would instead “use whatever vehicles I have in the office for daily use”.

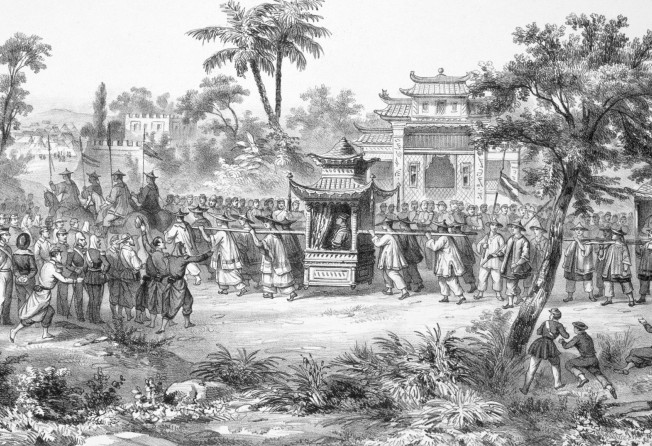

Every dynasty in imperial China had codified regulations on the permitted manner in which officials travelled on state business. The higher the person’s rank, the more elaborate it was.

It was a perk of their office but at the same time, official retinues travelling on provincial highways and city streets were also a public display of the regime’s authority and dignity.

Over the course of millennia, there were basically three forms of official transport for members of the nobility and government: horse-drawn carriages, palanquins carried by men, and horseback.

In the case of horse-drawn carriages and palanquins, there were strict rules regarding their style and decoration, as well as the number of horses and men that could be employed. Obviously, the higher the pay grade, the greater the number allowed.

Zhang Juzheng (1525–1582), a senior grand secretary (the de facto prime minister) of the Ming dynasty, once travelled from the capital in Beijing to his hometown in southern Hubei on a massive palanquin carried by 32 men, a distance of about 1,000 kilometres as the crow flies.

Such extravagant displays were rare, however, because they were so costly. While keeping horses and carriages was not cheap, employing palanquin carriers was even more expensive.

Even at the lower end of the scale, where palanquins were carried by two to four men, travelling officials took two teams of carriers with them, so that one team could switch with the other when they became tired or injured themselves.

Officials usually travelled on horseback during times when the government of the day wished to practise thrift or discourage profligacy. At times, it was even considered befitting to the martial ethos championed by certain emperors.

Anwar’s frugality and prudence in his choice of a prime ministerial vehicle is akin to imperial officials riding on horses as their form of transport. “Every ringgit counts,” he insisted.

Many hope that these measures are not simply a form of political theatre to burnish his reformist credentials. If they are genuine attempts at reform, then Anwar must ensure that they can be sustained until the new culture in government becomes normalised.

It may not happen tomorrow, but we live in hope that the day will eventually come.