British universities should welcome Chinese students, not seek to close the door

- Concerns over Chinese influence in universities and calls for the closure of Confucius Institutes cloud the issue when China literacy is needed more than ever

- The UK benefits not just economically and culturally from Chinese students, its top universities also shape world leaders

The number of international students studying in the UK has more than doubled over the past two decades, with some 680,000 currently enrolled. A single cohort contributes an estimated £28.8 billion (US$36 billion) to the UK economy, with each person £390 better off as a direct result.

It is not only financially that the UK benefits from international students – there is a huge amount of soft power gained, too. Last year, there were 55 serving world leaders who had been educated in the UK. Only the United States had more, with 67. Positive experiences and perceptions of Britain, its people and culture create an emotional bond between alumni and the nation. The trust created is invaluable for both diplomacy and trade.

Given these benefits, it may seem like a no-brainer that we should continue to encourage more international students to study in the UK. Yet, rising tensions between London and Beijing have led to intensifying debates over the number of international students studying in the UK, especially those from China.

Chinese students choose the UK for a variety of reasons – the quality of education, the cultural experience and the opportunity to enhance their English, to name just a few. Many are also eager to escape the most competitive education system in the world.

China’s gaokao, the gruelling end-of-school examinations that determine which universities students can gain admission to, is famously brutal. With such high and growing demand for higher education, many are choosing to study abroad, often at institutions significantly less competitive than the domestic alternatives.

Competition has become so intense that many feel trapped in a form of “involution”, or neijuan, – a never-ending rat race against fellow classmates, something that seems to have spread throughout Chinese society.

Mainland China sent more than 150,000 students to the UK in 2021-2022, according to the latest data from the Higher Education Statistics Authority, a number that has jumped by nearly 60 per cent in just five years. Chinese students now make up 22 per cent of international students in the UK.

As the number of Chinese students in the UK continues to rise, there have been growing concerns over the impact and there are now calls for universities to ensure they are sufficiently diversified in terms of their overseas tuition fee income.

Some fear Beijing could pull the plug at any moment and universities would be left with a significant financial hole to fill. Some parliamentarians have also argued that universities’ increasing reliance on Chinese students’ tuition fees could compromise the academic freedom of these institutions.

The Foreign Affairs Committee, in response to growing concerns, recently opened an inquiry into how universities engage with autocracies, questioning the measures they have taken to reduce their financial reliance on Chinese students, along with the influence of the Chinese Communist Party on their institutions.

The fact that more than 1,100 scientists and postgraduate students from China were rejected by Foreign Office vetting last year, up from 128 in 2020 and just 13 in 2016, illustrates how quickly the mood has changed.

News that Indian students coming to study in the UK had overtaken those from China last year is likely to be seen as a step in the right direction. But this is not the only concern being raised within higher education.

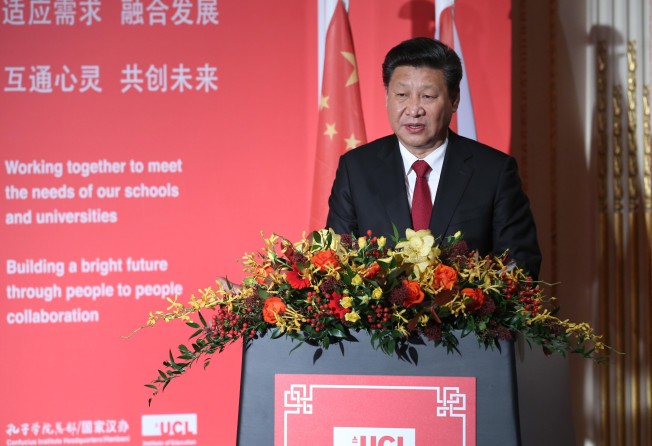

Confucius Institutes, established to promote Chinese language and culture, have been accused of overstepping the mark by influencing government policy, establishing science and technology partnerships and consulting major British organisations. There are now calls for all 30 institutes to be shut down.

Beijing, unsurprisingly, disputes these claims, but what has rather got lost in the noise is how their removal would significantly reduce access to Mandarin lessons for hundreds of students.

With the UK already significantly lacking in Chinese-language capabilities, urgent investment is needed to fill this knowledge gap, especially if the institutes do close down. Establishing new collaboration with Taiwanese institutes has been put forward as a possible solution, although this will do little to help cool tensions with Beijing.

The UK’s lack of expertise was highlighted last year when the Foreign Office revealed that only 14 officials were being trained to speak fluent Mandarin each year. Thankfully, this number is increasing across government, but it still remains far too low.

Greater investment is also needed in China literacy more broadly, especially in Chinese history, politics and law. The recent announcement that funding to develop China capabilities across the government will be doubled is welcome, but more is needed. Encouraging more British students to study in China may be a good starting point. Only through enhancing our understanding of China can we improve our resilience.

Chinese students coming to Britain provide real value, both culturally and economically, and their desire to choose the UK should be celebrated.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has classified China as an “epoch-defining challenge”, perhaps a downgrade from “the largest threat to Britain” which he declared last year. But relations remain frosty between London and Beijing.

The UK’s world-leading higher-education sector remains a key tool in shaping the views and values of world leaders. We should not lose sight of how valuable an asset this is, especially as the future leaders of China are deciding where to undertake their studies.

Connor Horsfall is a China specialist and consultant at Shearwater Global