02:14

Chinese reluctant to have children as China reports first population fall in 61 years

On February 28, the US Commerce Department put out a call for applications for US$39 billion in federal funds from the Chips and Science Act passed by Congress last year, with several strings attached. A significant one is the rule demanding chip makers ensure affordable, high-quality childcare for their workers.

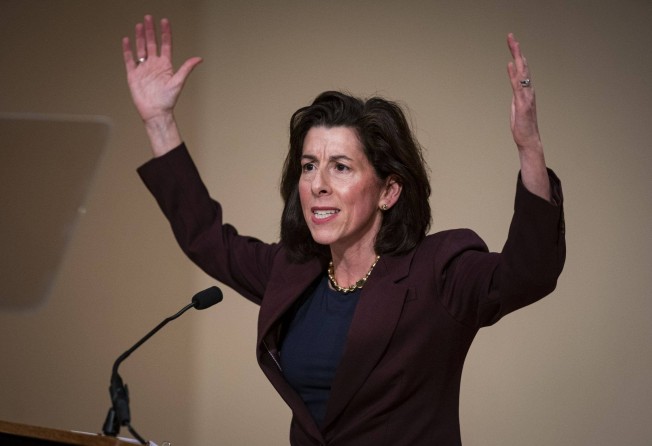

This is a strategic move that aims to mitigate US manufacturers’ struggles to hire skilled workers. As Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo said last month, the US is “in the middle of a tremendous labour shortage”.

Yet, it is not alone. China is also stuck in a similar, and perhaps deeper, quagmire. On January 17, the National Bureau of Statistics announced a population decrease of 850,000 people in 2022 - the first decline in 62 years.

To make matters worse, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security estimates an additional drop of 35 million people in the next five years. In the past four decades, China has tapped into its massive population of low-wage labourers to become the world’s manufacturing hub for major technology companies.

Apple, for instance, produces more than 95 per cent of its iPhones, AirPods, Macs and iPads in China. Now, that era may be coming to an end.

China has two potential policy solutions. First, policymakers could speed up the installation of industrial robots on factory floors.

For instance, the country’s Ministry of Industry and Information released the “Robot + Application Action Plan” in January, aiming to increase the industrial sector’s robot density. Yet, China’s robotic workforce is still vastly outnumbered by human workers, with 187 per 10,000 employees.

Moreover, even if the government could roll out robots faster, automation is still not advanced enough to be a viable alternative to highly skilled personnel. Apple has attempted to replace workers with robots, only to realise products such as the iPhone are still best assembled by hand. The lesson is that humans are better.

The key to maintaining humans’ edge is education. That leads to China’s second policy prescription: vocational training.

President Xi Jinping has promised to accelerate the construction of a modern vocational education system. However, from 2015 to 2021, some 3,900 vocational schools were closed. At the same time, more than 90 per cent of vocational school students said they believed their curriculum did not reflect industrial trends.

Yet, the most insurmountable barrier to a more effective system of vocational education in China lies in its culture.

In Chinese society, vocational schools are still regarded by many as a place only for students who fail the academic-track high school entry exam. As a result, it is not surprising that about 70 per cent of vocational students said their greatest hurdle in job hunting was social recognition for their degrees.

It will take a combination of government funding, educational reform and cultural engineering to tackle the issues hobbling the development of China’s vocational education system.

Across the Pacific, an analogous phenomenon is playing out in the US. Amanda Chu writes in the Financial Times that, after decades of “discouraging Americans from vocational work, construction companies warn [that] the country’s industrial policies and the labour market are headed for a collision”.

In response, Raimondo has urged semiconductor companies to collaborate with educational institutions to train 100,000 new technicians in the next 10 years. In addition, she argued the US needs to triple the number of graduates in science and engineering to successfully rebuild its semiconductor fabrication industry.

Raimondo is not wrong. Take Taiwan’s rise in the technology industry. In the 1980s, a critical element in helping to cultivate its indigenous technology ecosystem was the increase of human capital. For instance, more than 30 per cent of Taiwanese students who studied engineering in the US returned to the island, compared to only 10 per cent in the 1970s.

Direct public funding could boost innovation in the short term. However, research shows that increasing the supply of human capital remains the most effective policy tool for governments to sustain technological advancement in the long run.

All told, the US-China technology war could boil down to a contest for talent – not just for engineers working at the technological front lines but also the workers who construct the basis of those front lines in the first place. In other words, the quantity and quality of labour and scientists will ultimately shape the outcome of US-China technology competition and, with that, the contours of the 21st century.

Chin Hsueh is a Master of Science in Foreign Service candidate at Georgetown University