Unveiling the stories of Hong Kong’s early Japanese residents in Happy Valley’s cemetery

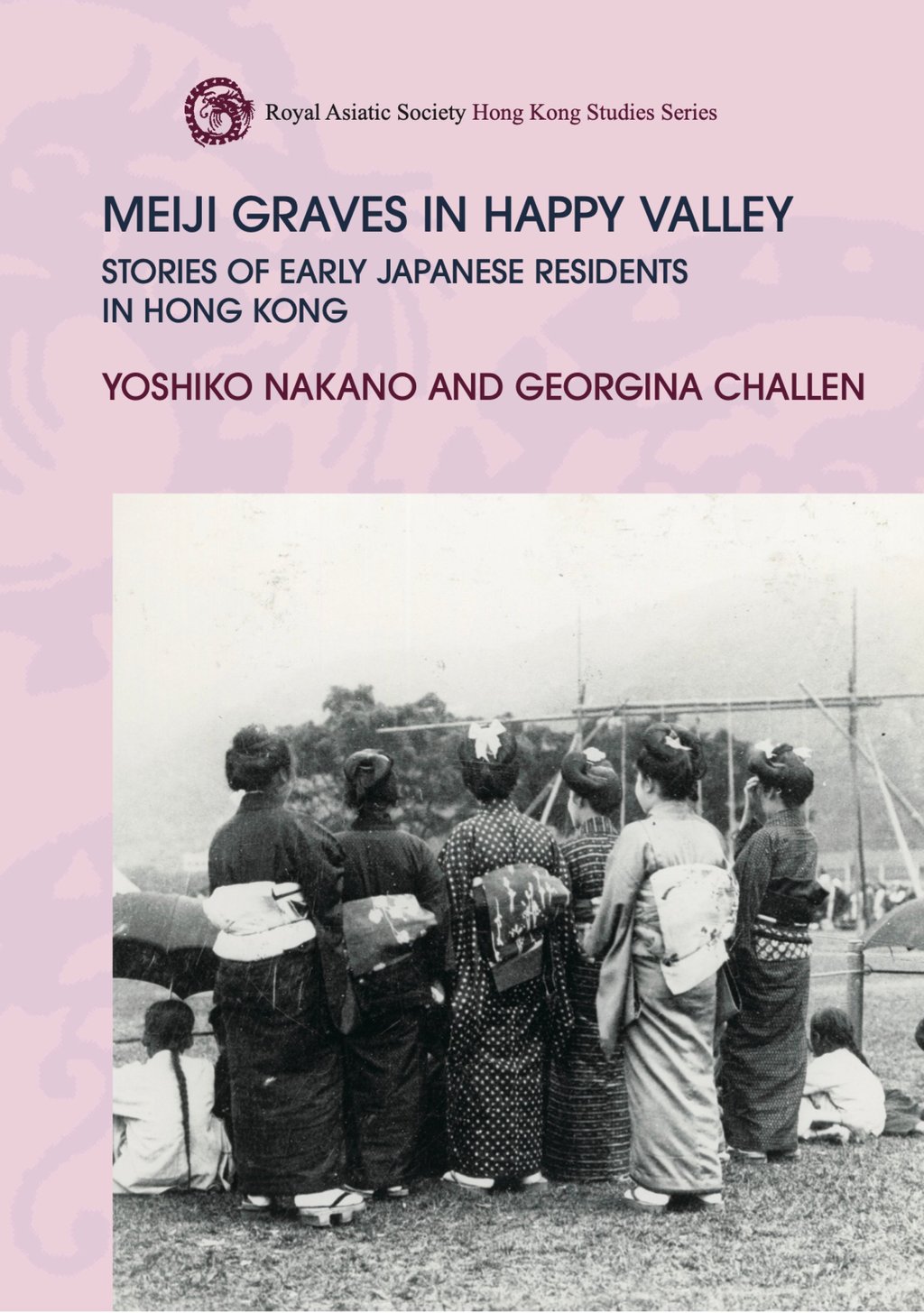

Meiji-era prostitutes, whose names are etched in stone, find a voice in a new book by Georgina Challen and Yoshiko Nakano

One May day in 1884, a Japanese woman called Saki Kiya received a letter at her Hong Kong address. It was from her family, who said that her father was ill and asked her to return home to Japan. She did not have enough money for the voyage and soon, another letter arrived informing her that he had died. On a Sunday evening in June, she left her residence at 27 Graham Street. Some hours later, her body was found floating in the harbour with, as the China Mail put it, “a pretty heavy stone” tied into each sleeve of her loose jacket. Her shoes had been placed neatly nearby.

The graves lie in two sections along the upper slopes of the cemetery. This wasn’t deliberate – a good deal of headstone-jumbling has taken place over the years, especially when the nearby Aberdeen flyover and tunnel were constructed in the 1980s – but the division is appropriate because, as the book vividly conveys, from its earliest stages the Japanese community was bisected between company executives (always men) and the karayuki-san or prostitutes (always women). The small businesses that fell in between – kimono dealers, hairdressers, porcelain suppliers – depended on prostitution for their income. One of the more astonishing aspects, to a 21st century reader, is the role of the Japanese Benevolent Society, which had no religious connections but was set up in 1890 to help the sick and to pay for the burial of the destitute. It funded at least 48 of the identifiable Japanese graves, mostly those of the karayuki-san; and its benevolent members were those who profited, to some extent, from the sex trade.

“It’s definitely odd,” agrees Nakano on a video call from Tokyo, where she is now a professor in the Department of International Digital and Design Management at Tokyo University of Science. “Some of those people involved in trafficking enjoyed much higher status in Hong Kong than in Japan. That contradiction, that ambivalence, is very characteristic of the two halves. It was the main thing we found out and it was shocking to us. But that’s how things were.”

Nakano arrived in Hong Kong in 1997 and went on to teach Japanese studies at the University of Hong Kong. For a time, she was the only female board member of the Hong Kong Japanese Club. Although the club had been involved with the cemetery since 1982 and holds an annual ceremony to honour its Japanese occupants, Nakano, author of Where There are Asians, There are Rice Cookers: How “National” Went Global via Hong Kong (2009), wasn’t initially gripped. (“I’m more of a post-war person.”) But in 2020, the club initiated a project to document some of the Meiji graves. Nakano was involved and asked Challen, who doesn’t speak Japanese, to assist with English-language research and writing; and it was Challen who found the China Mail report about Saki Kiya. The women realised many more human-interest stories had been buried in Happy Valley and that this lost seam of history deserved a book.