The presence of microplastics in archaeology sites could prompt a major industry rethink

- Typically archaeologists try to leave artefacts in their original resting position

- But the concern is that plastics could toxify deposits, maybe prompting excavation

Microplastics are everywhere, having been found in the stomach of a dead whale at Point Nemo – the most remote point on the planet – and even inside human blood. We can now add “archaeological excavation sites” to that list.

In early March, a team of scientists from the universities of Hull and York published a study in the peer-reviewed journal Science of The Total Environment that outlined the discovery of microplastics at two excavation sites in the historical British city of York.

“We are getting used to reading articles about microplastics in the food chain and even our bodies. Our research has revealed that we are also identifying microplastics in archaeological deposits several metres deep,” said Paul Flintoft, a regional manager at York Archaeology and author of the study.

Flintoft told the Post that the discovery suggests that certain artefact deposits believed to remain unchanged are, in fact, constantly evolving.

“Contemporary activities are leading to the contamination of a unique scientific resource,” he said.

Microplastics are defined as plastic particles ranging from one-thousandth of a millimetre to 5mm (smaller plastic pieces are called nanoplastics). They are a pernicious problem in the battle against plastic pollution because they easily pass through filters, netting, and other tools we use to clean up plastic waste.

The team found 16 unique microplastic polymer types during their investigation of the two sites in York.

The teams believe their pilot study, a small-scale project meant to demonstrate proof-of-concept for future research at a grander scale, is the first time scientists have found microplastics at an archaeology site.

“Where this becomes a concern for archaeology is how microplastics may compromise the scientific value of archaeological deposits,” said David Jennings, the chief executive of York Archaeology, in a statement.

“The presence of microplastics can and will change the chemistry of the soil, potentially introducing elements which will cause the organic remains to decay.”

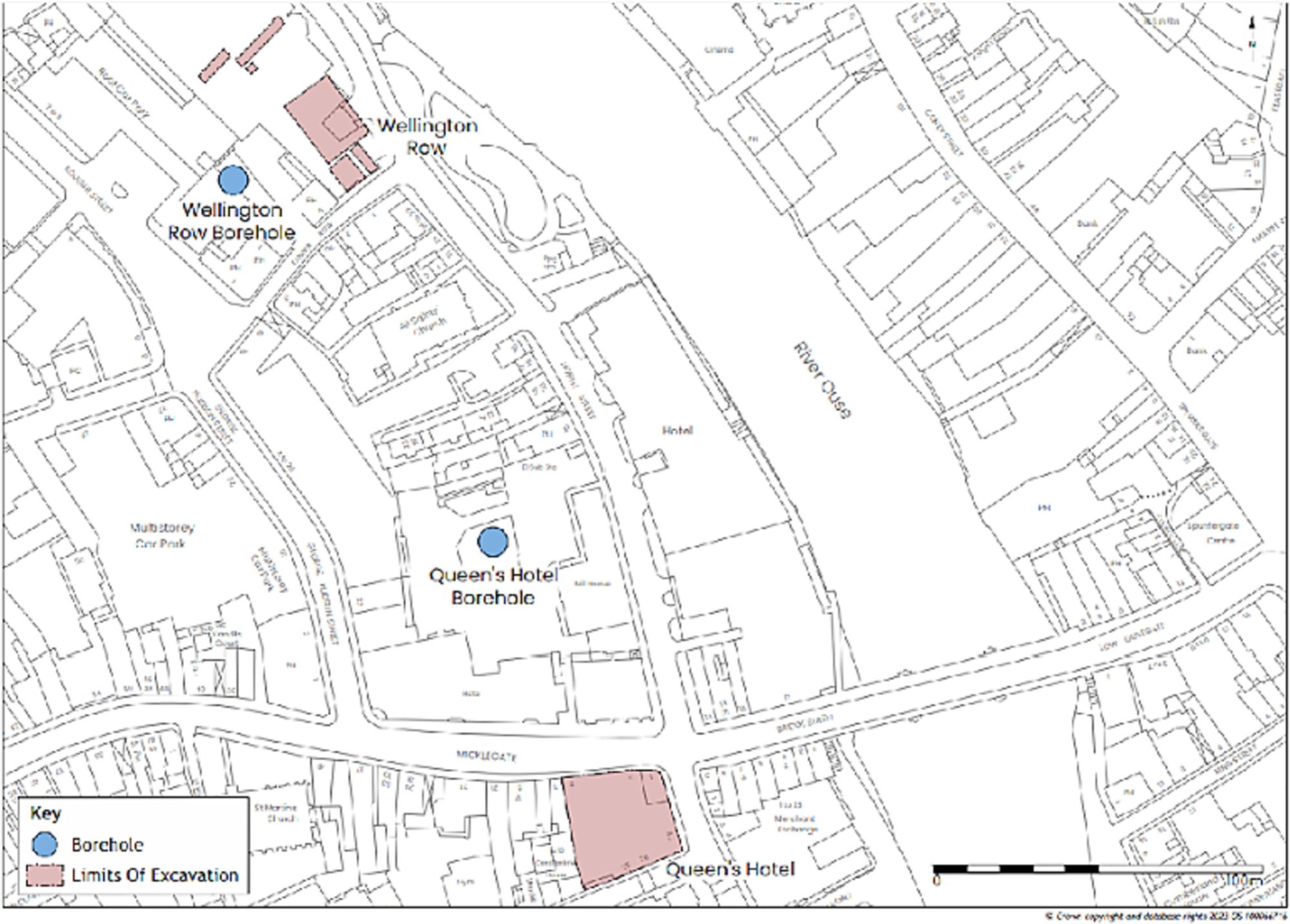

The analysed sites were Queens Hotel and Wellington Row. The team of archaeologists chose the sites because they represent nearly 2,000 years of continuous urban occupation, allowing the team to analyse soil dating back to the first century for the Queens Hotel site or the second century at Wellington Row.

The archaeologists investigated archived soil from the original excavations in 1988 and compared it to more modern soil from 2023. All four samples contained microplastics, and, interestingly, they all had very similar levels of plastic.

The team believes the microplastics accumulated over the past century, and they discovered types of plastics that were not commonly found until after World War II.

One intriguing discovery that the scientists could not account for was that the archived samples from 1988 contained more plastic than the soil excavated last year.

For example, at the Queens Hotel site, the team found microplastics in the upper, middle and lower borehole samples from the archived soil, but only the middle segment from the soil unearthed last year.

While the types of plastic between the samples varied wildly, there was no consistency indicating why a specific plastic was found at a certain site.

One potential consequence of the pilot study is that assuming microplastics are found at archaeology sites beyond York, it might prompt a rethink of the culture of leaving certain archaeological sites in situ, a Latin term meaning “in its original place or position.”

Flintoft said global archaeological best practices recommend leaving archaeological deposits in situ “for future generations with improved scientific techniques to excavate”.

“Our argument is that if we reveal that microplastics could toxify archaeological deposits, we should perhaps excavate them rather than leave them to decay further,” he said, adding: “This is rather controversial.”

Flintoft added that the team has not yet determined whether the plastics can toxify the deposits and is simply highlighting the risks at the current stage.

Additionally, the sites in York are located in a dense urban environment, so microplastics might not be an issue for sites found in more arid habitats.

Flintoft suggested that because we now have awareness that microplastics could be widespread, archaeologists should monitor their presence as part of their excavation procedure to help the industry gain a clear understanding of the scope of the problem.

“We are applying for funding to take this research to the next stage. We want to understand the risks microplastics pose to archaeological remains and how to better monitor contaminations,” said Flintoft.