Explainer | How Beijing is leading an overhaul of Hong Kong’s election systems

- In past attempts to reform election processes, city’s leader acted first by approaching Beijing

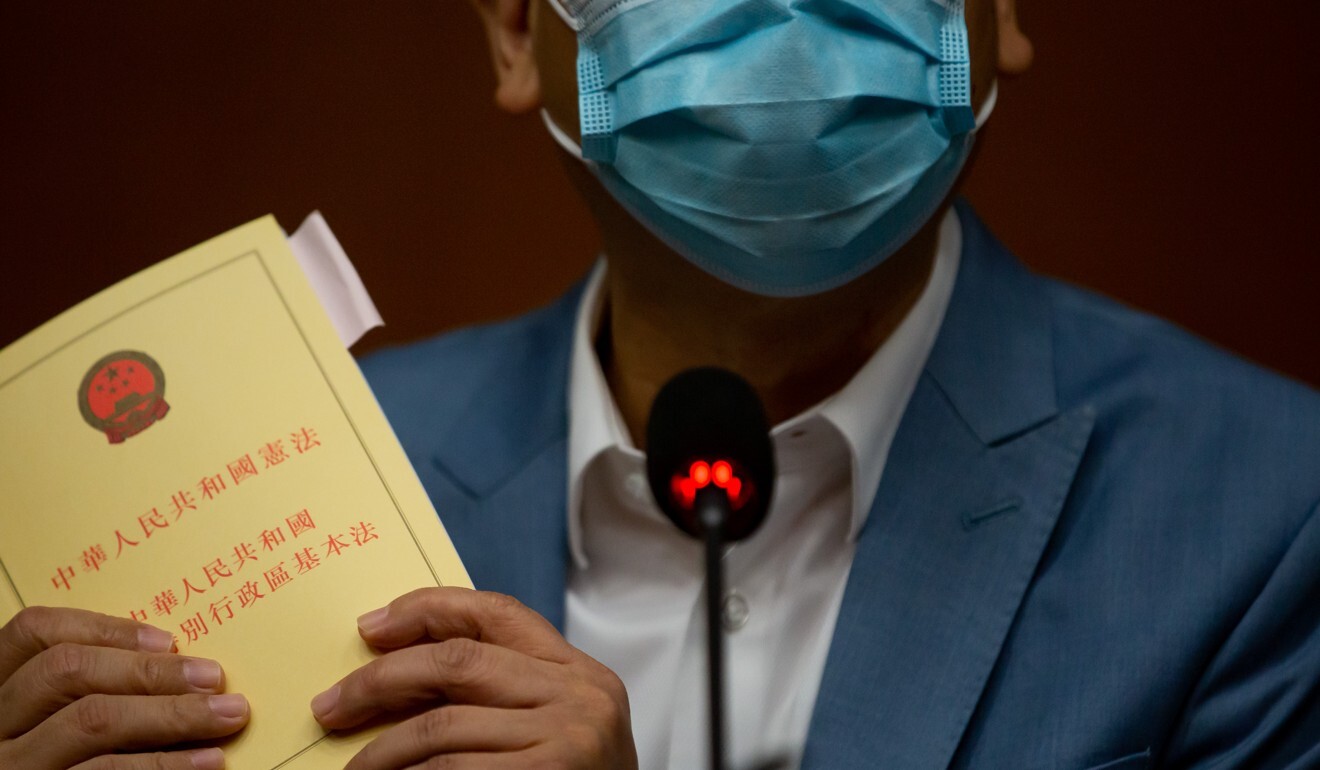

- Critics say proposals of drastic change go against promise of universal suffrage in Basic Law

A “democratic electoral system with Hong Kong characteristics” is what Beijing is aiming for in its proposed overhaul of the city’s electoral systems, and the central government hopes the imminent changes will stop opposition activists from using their public office to call for foreign interference.

A look at Hong Kong elections and political reforms over two decades

Beijing officials argued the changes – which include increasing the number of lawmakers chosen by a select group – are necessary to tackle national security threats. But critics warned that changing the rules of the political game so drastically went against Beijing’s promises, enshrined in the Basic Law, which stipulate universal suffrage as the ultimate aim of the city’s constitutional development.

Here is a summary of how Hong Kong’s electoral systems have evolved since Britain returned the city to China in 1997, and what the proposed changes might mean.

Are there “standard procedures” for reforming Hong Kong’s electoral systems?

In 2004 Beijing set out a “five-step procedure” for making changes to the way the city’s leaders and lawmakers are selected.

First, Hong Kong’s chief executive must submit a report to the National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC)on the proposed reform and await its green light.

On receiving the go-ahead from Beijing, the Hong Kong government proceeds to step three, securing support from at least two-thirds of the city’s lawmakers for its proposals. Once the proposed legislation is passed, the final steps are obtaining the endorsements from the city leader and the national legislature.

The first two steps, introduced by the central government in 2004, have long been criticised by Hong Kong’s opposition activists for allowing Beijing to dictate the pace of constitutional change, let alone impose more restrictions on reforms.

One example cited frequently by the opposition is the so-called “August 31 decision” that Beijing laid down in 2014 when the city sought to introduce universal suffrage for the election of the chief executive. Beijing decided instead that only two or three candidates would be allowed, and they would need majority support from a nominating committee likely to be dominated by its loyalists.

What happened in previous political reform attempts?

Hong Kong has gone through three rounds of political reform since 1997, each leaving society painfully split. Only one attempt bore fruit.

In 2005, then chief executive Donald Tsang Yam-kuen initiated the first changes, proposing to double the size of the Election Committee which picks the city’s leader to 1,600 members, while also increasing the number of seats in the Legislative Council from 60 to 70. Both suggestions were voted down by pan-democrats who criticised Tsang for failing to provide the timetable for making the changes. The government said its hands were tied as Beijing had already ruled out universal suffrage in the city’s 2007 and 2008 elections.

Tsang tried again in 2010 to expand membership of both the Election Committee and the Legco. Unimpressed, the pan-democrats argued that the government should also scrap the functional constituencies – the trade-based Legco seats returned by a limited number of voters. In a highly controversial move, the opposition Democratic Party struck a compromise deal with mainland officials after secret negotiations at Beijing’s liaison office in Hong Kong. This was to allow the lawmakers for five newly created seats – originally meant to be chosen by district councillors – to be picked by general voters.

In 2014, a government task force led by then chief secretary Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor recommended allowing Hongkongers to choose their next leader through a “one man, one vote” system for the first time, by 2017. Opposition activists and lawmakers wanted changes to the way in which candidates would be picked for the 2017 race. They suggested enlarging the franchise of the 1,200-strong committee that nominated candidates, or allowing members of the public to name the hopefuls. That year’s Occupy protests, which saw mass sit-ins that shut down parts of the city for 79 days, resulted in Beijing refusing to budge on electoral reform. The proposal was rejected by opposition lawmakers the next year.

How is Beijing planning to change the rules?

Instead of the“five-step procedure”, Beijing would now take the lead in spearheading reform, Wang Chen emphasised on Friday.

This time, the national legislature itself will move a resolution on March 11 spelling out the basic principles and core elements of the proposed reform. It will then endorse its apex body – the NPCSC – to amend the Basic Law’s annex I and II, which spell out the rules for electing Hong Kong’s chief executive and lawmakers respectively.

After that, only a simple Legco majority will be needed to pass the local legislation based on the Beijing resolution.

Maria Tam Wai-chu, vice-chairwoman of the Basic Law Committee, pointed out earlier that the five-step procedure could not apply as Hong Kong did not have enough lawmakers to endorse the proposal following the mass resignation of opposition members last November.

Fifteen opposition lawmakers resigned in protest, after four of their colleagues were unseated following a resolution passed by Beijing. The 70-seat Legco has only 44 lawmakers now.

What is Beijing proposing now?

Wang made clear the reforms were focused on “reconstructing” and “empowering” the Election Committee which chooses Hong Kong’s chief executive. It looks set to be strengthened and dominated by the pro-establishment camp.

Under Beijing’s plan, the 1,200-member committee may add another 300 voters and have its powers widened. Aside from picking the city’s leader, it will also nominate all candidates for Legco elections, and elect a large number of lawmakers from its own ranks.

Sources told the Post that Legco will be expanded from 70 to 90 seats, with at least a third of the seats set aside for lawmakers from the Election Committee.

Wang said a full mechanism to vet candidates for various elections would also be established to form “a new democratic electoral system with Hong Kong characteristics”.

Do the proposed reforms run against the Basic Law?

Attacking the proposed changes, Democratic Party veteran Lee Wing-tat said they were very likely to rule out the opposition from future elections, a regression going against a goal enshrined in the Basic Law.

Article 45 of the Basic Law states that the “ultimate aim” in Hong Kong is for the chief executive to be selected by “universal suffrage upon nomination by a broadly representative nominating committee”.

Lee, who took part in the secret closed-door negotiations with Beijing in 2010, said the days when central government officials were prepared to listen to Hong Kong’s opposition figures were over. Now that Beijing had tightened its grip on the city, he said, universal suffrage would not happen in the foreseeable future despite being promised in the Basic Law.

“These reforms they are talking about will set more hurdles for chief executive and Legco election hopefuls. Instead of going forward, these are going against the promise in the Basic Law that we will achieve universal suffrage in an orderly and gradual manner,” he said. “But what can you do? Nothing.”

Ip Kwok-him, a Hong Kong delegate to the NPC, insisted the reforms had nothing to do with the city’s democratic process.

“Beijing has to deal with imminent problems after the social unrest in 2019. There will still be universal suffrage, but it depends on how you define it.”

Referring to the 2014 proposal for the city leader’s election, which would have allowed Beijing to effectively vet candidates, he added: “The opposition bloc said the ‘August 31 framework’ was not universal suffrage, but the central government did not see it that way.”

Executive councillor Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee said Beijing’s hand was forced by Hong Kong’s “chaotic Legco” in which opposition lawmakers had blocked attempts at good governance and dragged out the passage of important legislation.

But Professor Johannes Chan Man-mun, chair of public law at the University of Hong Kong, said elections might become meaningless if the threshold for participation was set so high that only those preferred by the authorities could take part.

“It’s not about how many seats there are. It’s about whether the election arrangements can be fair and open,” said Chan, adding that residents might become indifferent to polls held in such a way.