The battle over Hong Kong’s controversial small-house policy is not finished

- The High Court has upheld the right of indigenous male villagers to build homes on private land

- But few were satisfied by the judgment, with challenges and policy headaches still to come

A recent court decision on a controversial policy affecting New Territories villagers has reminded Hongkongers that when it comes to housing, as in so many other areas of life, people are born unequal.

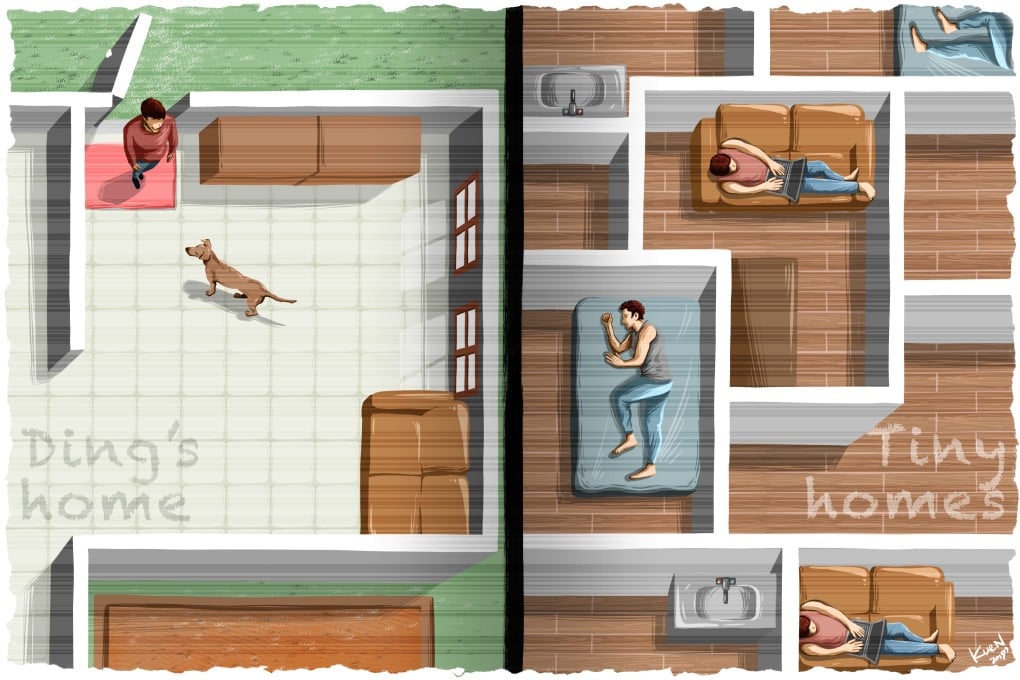

While most of the city struggles with astronomical property prices for tiny homes and a severe shortage of land for new developments, it is a different story for males over 18 years old who can prove their forefathers lived in rural villages more than a century ago.

Thanks to a colonial-era law, these males – known as ding – are allowed to build “small houses” on their farmland without paying a hefty fee that reflects the value of the property after development.

By forking out about HK$5 million (US$637,500) to erect and furnish a three-storey house of up to 2,100 sq ft — a spacious home by Hong Kong standards — they can own a property easily worth HK$20 million or more.

Since their introduction in 1972, the so-called ding rights have resulted in 43,000 such houses being built across the rural New Territories. In a city starved of space, some 5,000 hectares – almost a fifth of the size of Hong Kong’s urban areas – are locked up for such low-rise development.