Hong Kong’s biggest health crisis in 25 years: why did city stumble over Covid-19? Experts say it was too slow to change tactics, inflexible, put politics first

- City overcame past health crises, including Sars, only to falter when Omicron variant arrived

- Insistence on ‘zero infections’ left authorities unable to act swiftly when needed, experts say

Cindy Wan Yuk-sin spent nearly two months in hospital in 2003, including more than 20 days in a coma, after being struck by Sars, the killer severe acute respiratory syndrome that emerged suddenly and affected several countries that year.

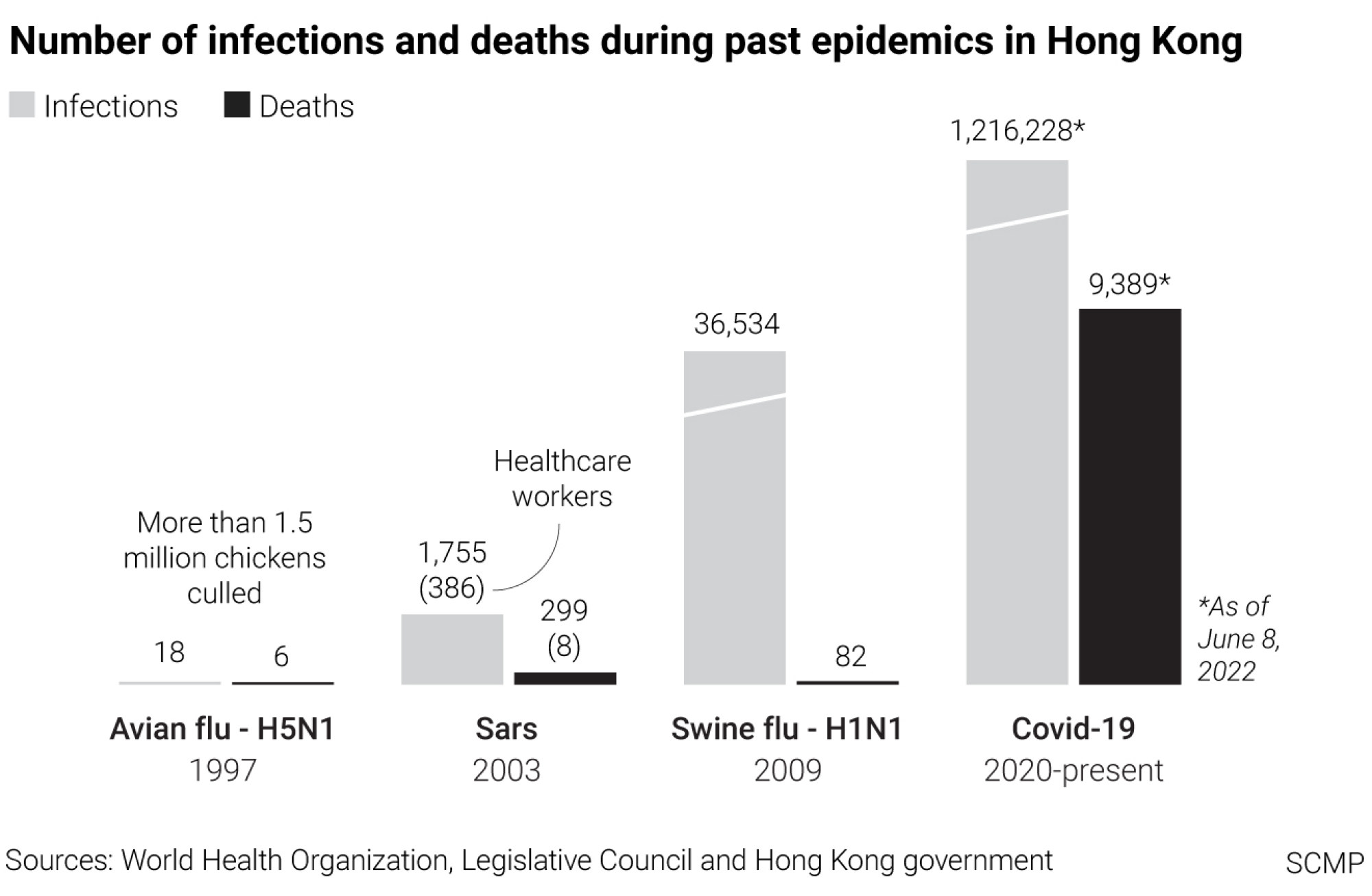

In Hong Kong, the epidemic lasted three months, leaving 1,755 infected and 299 dead.

Wan came close to death. The former restaurant cashier was grateful she survived, and went on to raise three children with her husband, a delivery man.

Then, in March this year, she tested positive for Covid-19. The pandemic had swept the world since early 2020 but Hong Kong was now in the grip of a surging fifth wave of infections.

As thousands of Hongkongers fell ill and hospitals could not cope, Wan, now 60, did not seek medical help. She was put off by scenes of numerous patients, mostly the elderly, waiting on stretchers outside public hospitals for days.

“I hoped that I didn’t need to go to hospital,” Wan said. “It would have taken so long for an ambulance to arrive if I made an emergency call.”

Wan could not understand why Hong Kong was struggling so hard when it had beaten Sars and other major public health crises over the years.

“We managed the situation in 2003, why couldn’t we handle it this time?” she asked.

For the past 25 years, Hong Kong has relied on a strategy of containment to tackle public health emergencies.

That meant the mass culling of more than 1.5 million chickens during the bird flu epidemic of 1997, when 18 people were infected and six died.

When Sars struck six years later, every infected person was sent to hospital and all close contacts were quarantined.

Hong Kong fended off the Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers) after there were outbreaks in Saudi Arabia and South Korea in 2014 and 2015. The city stayed on high alert and every suspected case was screened.

Even after Covid-19 arrived, the containment strategy appeared to work in the first four waves of infections from early 2020 to mid-2021 and transmissions stayed under control.

Then came the Omicron variant of the coronavirus, and things fell apart rapidly early this year.

Highly transmissive but less virulent than the earlier Alpha, Beta and Delta forms of the coronavirus, Omicron sparked the fifth wave of infections which pushed Hong Kong’s healthcare system to the brink of collapse, exposing weaknesses in the city’s response to a constantly evolving public health crisis.

At its worst point in March, 58,757 new infections and more than 200 related deaths were reported daily. The fifth wave started to subside in May but case numbers have resurged again in recent weeks. On Thursday, the city recorded more than 1,000 local infections, with 94 imported cases.

Omicron has brought Hong Kong to its knees. How did it all go wrong?

Public health sector veteran Dr Leung Pak-yin, who was chief executive of the Hospital Authority from 2010 to 2019, said Hong Kong was slow to change tactics when the new variant showed up.

“If a virus is highly transmissive, the situation cannot be handled with containment,” he said. “The tools used for containment, such as isolation and hospitalisation, will not be able to cope.”

Instead, Hong Kong should have switched to a combination of containment and mitigation measures. That called for focusing care on high-risk groups such as elderly residents in care homes, and allowing others with low-risk factors to remain in the community even if infected.

That way, he said, hospital beds and intensive care units would be saved for the more seriously ill.

The availability of vaccines, effective oral drugs and diagnostic kits all created conditions for Hong Kong to switch safely to mitigation.

“The government did not turn around fast enough,” said Leung, who spent 34 years in the public health system and led the Centre for Health Protection which was set up in 2004, after Sars, to focus on disease prevention, surveillance and control.

Why did the city falter in its response when, since its return to China in 1997, it had dealt with a series of public health emergencies, with Sars as one of the defining moments?

Aside from establishing the Centre for Health Protection after Sars, the city added isolation facilities to major public hospitals, an infectious disease centre was set up at Princess Margaret Hospital, and Hongkongers accepted the need to wear masks in an outbreak of respiratory infections.

One reason for the government’s slow response to the fifth wave, Leung reckoned, was its insufficient focus on tackling the outbreak.

“The focus was not on handling the epidemic itself, but on whether we should pursue zero infections,” he said, adding he believed the government placed politics above the need to control the epidemic and “thought too much”.

With Beijing’s help, Hong Kong began building more community isolation facilities in late February as the fifth wave was raging.

But the number of cases had begun easing by the time most of these facilities were completed, leaving them hardly used or left on standby. A makeshift hospital built in Lok Ma Chau and meant to be operated by mainland Chinese healthcare workers was not used after it was completed in April.

There were also heated debates over whether the city should follow the mainland’s strategy of carrying out compulsory testing of the entire population to cut the transmission chain.

Is a sixth wave of Covid-19 infections about to hit Hong Kong?

Although outgoing city leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor said there would be mass testing for all, it did not happen in the end. The pressure from different quarters on whether to proceed also affected the government’s ability to focus on the crisis, Leung said.

He recalled how differently the situation turned out in 2009, when Hong Kong was hit by the swine flu pandemic and at least 36,000 people fell ill.

From early on, he said, health officials had an idea of when they might have to adopt a mitigation approach, if the rapid rise of infections threatened the collapse of the public healthcare system.

The swine flu virus was highly transmissive but less virulent than Sars, and the availability of Tamiflu, highly effective against swine flu, allowed officials to change their approach quickly, Leung said.

Just two months into that pandemic, the government moved from containment to mitigation.

The same nimbleness was not evident during the fifth wave of Covid-19 infections.

“If I need to spend a lot of time handling isolation facilities, or considering whether to carry out compulsory universal testing, I would be wasting a lot of time,” Leung said.

New Covid cases drop below 300 mark in Hong Kong, ‘fifth wave under control’

Tim Pang Hung-cheong, a veteran patient rights advocate, felt the same way about the government’s response to the fifth wave of infections.

“Hong Kong did not have enough hospital beds and makeshift treatment facilities to treat every patient, yet the government was still mulling over going ahead with universal testing,” he said.

“We were drifting and getting nowhere, and officials lacked the ability to move quickly as new situations emerged.”

Pang said the most basic of patients’ rights was the right to treatment, and this came under great stress during the worst of the fifth wave.

That was evident when some Covid-19 patients, including the old and frail, were forced to wait in the car parks and other open spaces of public hospitals for days, braving the cold and rain.

Pang also noted that the NGO sector, including his group, had to step in where the public sector failed, by delivering food, medicine and essential supplies to elderly people isolating at home.

Anthony Wu Ting-yuk, who was chairman of the Hospital Authority from 2004 to 2013, said flexibility was crucial in handling a crisis, but there was not enough evidence of it during the fifth wave.

To him, the sight of frail patients waiting outside public hospitals for days in February was evidence of inflexibility.

Coronavirus: what is Hong Kong’s dynamic zero-infection strategy?

He said every hospital could have freed up physiotherapy space to take in those patients sooner, but hospitals only moved them indoors after city leader Lam requested it.

“Was our system not flexible enough, or were the reporting lines not clear enough? I think these are worth reviewing,” Wu said. “Was the coordination between hospital clusters, or within the head office, not good enough?”

He said there ought to be an independent and thorough investigation into the government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic to get the city prepared for the next crisis.

“We are not trying to finger-point, but to learn a lesson,” Wu said. “If we face another major crisis, how should we cope?”

At the height of the fifth wave, Carrie Lam’s government also admitted to another weak link in the healthcare system – the management of elderly and disabled care homes, with more than half of the deaths then coming from there. The government has pledged a review but much remains to be seen if it will get anywhere.

Government pandemic adviser Professor Yuen Kwok-yung, who became well known during Sars, lamented that many suggestions made after that outbreak were not implemented.

For example, he said, experts had proposed setting up infectious diseases centres at three public hospitals, but only one was established at Princess Margaret Hospital.

A rapid, electronic and multilayer contact-tracing system should also have been in place to quickly contain the first cluster in an outbreak, but this suggestion “didn’t seem to have made much progress”.

The result was that Hong Kong was underprepared and responded too slowly when infection numbers shot up during the fifth wave of Covid-19.

Hong Kong doctor recalls feeling helpless at height of city’s fifth Covid wave

“When the preparation is not enough, and the response is not fast enough, it will be difficult,” he said, though he acknowledged that frontline healthcare staff had done their best in combating Covid-19.

Cindy Wan survived Sars in 2003, but was among those who did not seek medical help when she fell ill with Covid-19 during the fifth wave of infections.

She only relied on over-the-counter medicines for her itchy throat, cough and fever. She stayed home for nearly three weeks as her symptoms gradually eased.

Some days she wonders at the way she cheated death in 2003 and earned 19 years of life after Sars, only to be infected during the pandemic.

“Why did I win this first prize again?” she asked.