Chinese score lowest in European-American research team’s ‘honesty’ study – but method may be flawed

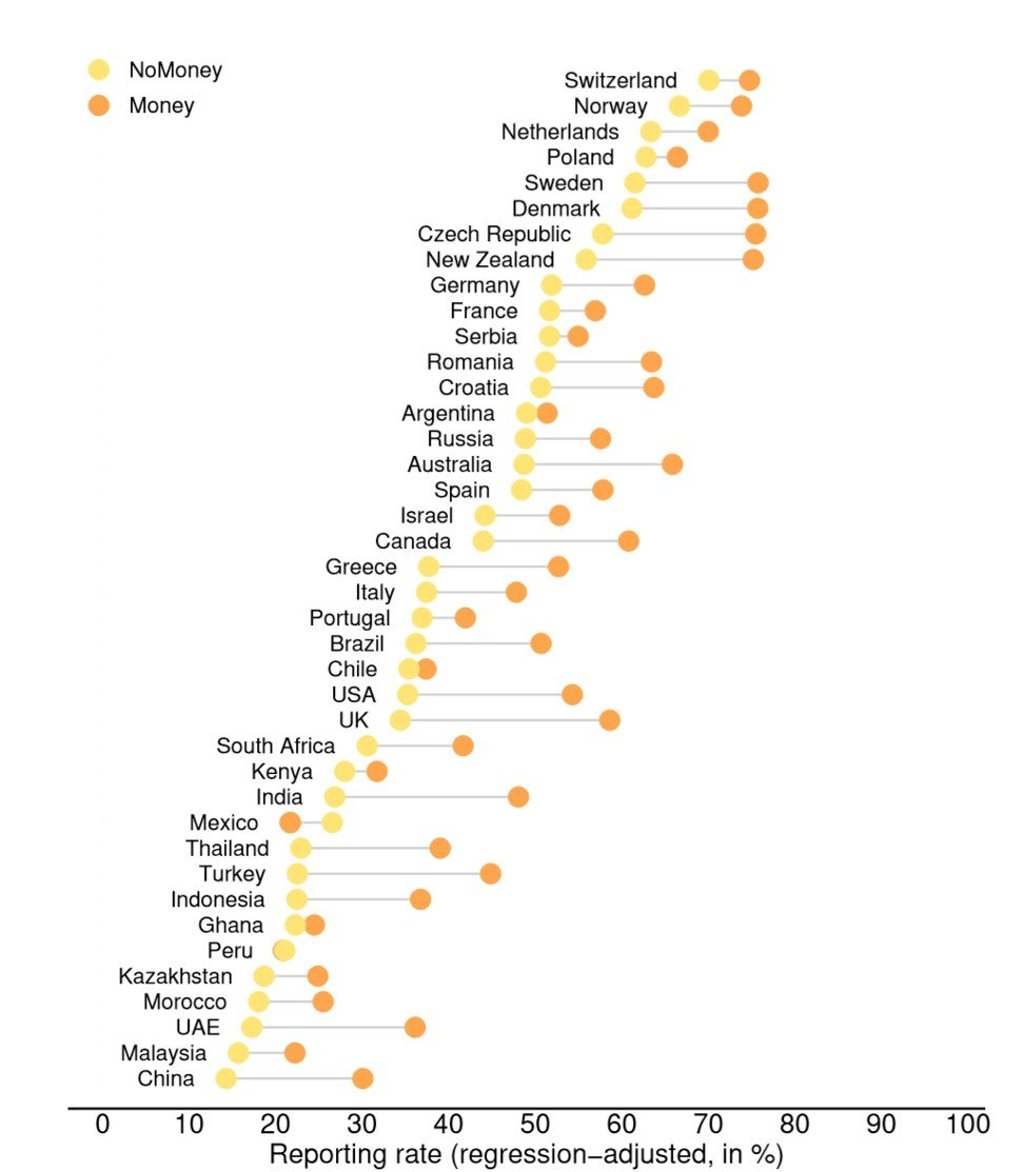

- Four-year project ranks honesty of 40 countries by their citizens’ willingness to report a lost wallet

- Switzerland scored highest overall, while the US and Britain placed in the middle of the pack

Chinese people rank at the bottom in a controversial study that measures the honesty of 40 countries by their citizens’ willingness to report a lost wallet.

China’s citizens were the least willing to report the lost wallet, according to a European-American research team that conducted the four-year study led by scientists from the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

Switzerland scored highest overall, followed by other European countries, including Norway, Netherlands, Poland and Sweden. The United States and Britain placed in the middle of the pack.

China shared the bottom rankings with the United Arab Emirates and Malaysia, as African and Asian countries generally received poor grades.

“Honest behaviour is a central feature of economic and social life,” the researchers wrote in their paper, “Civic honesty around the globe”, published in the latest edition of the American peer-reviewed journal Science.

“Without honesty, promises are broken, contracts go unenforced, taxes remain unpaid, and governments become corrupt,” they said.