A geologist’s earthshaking shift: publishing his discovery in a Chinese-language journal

When Lu Hongbo rewrote the history of where tectonic plates collided in China, he chose a Chinese publication to do it in: ‘No language is more beautiful than Chinese’

As he made his way up the southern foot of Langshan Mountain, on the western arm of Inner Mongolia’s Yinshan range, Lu Hongbo had a lot on his mind. The geologist knew his research into tectonic movements in northern China might draw sceptics and criticism because it was challenging long-standing theory. This very field trip was almost cancelled due to a lack of funding.

Then, of course, there was the diagnosis of leukaemia Lu received a year earlier. He was relying on a generic drug from India to fight the disease. How long, really, did he have?

Study led by Chinese geologist could help predict earthquakes under Tibetan plateau

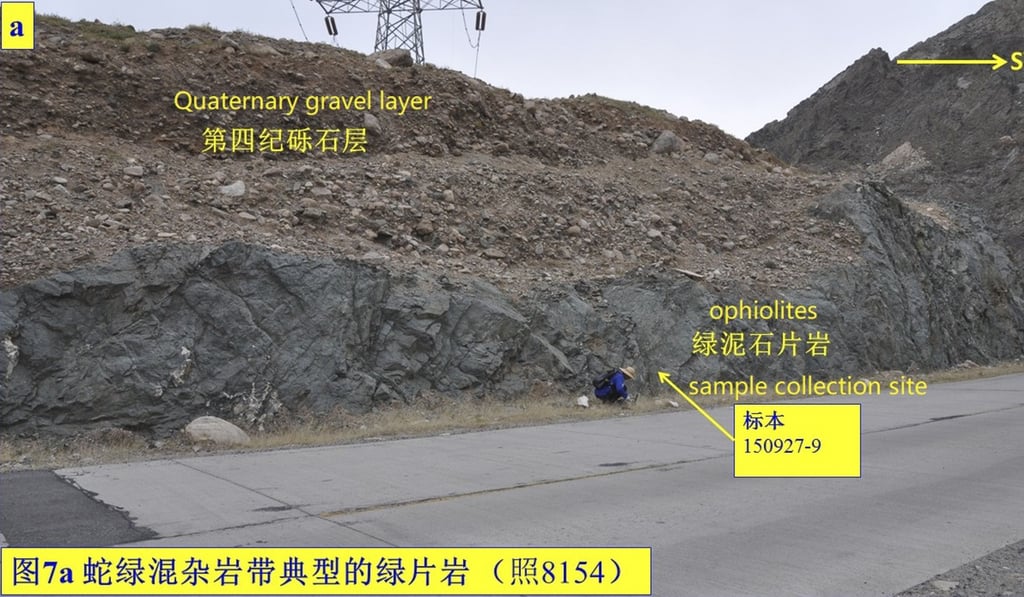

Suddenly, driving up a mining road cut through the middle of the mountain, Lu slammed on the brakes of his SUV, all those thoughts flying from his head. Some of the roadside rocks exposed a dull greenish colour in the sunshine that played among the cliff shadows. There was only one explanation for that colouring: the rocks were ophiolites, the remnants of ancient oceanic crust – found in ranges like the Alps and Himalayas. They were markers of titanic collisions between the planet’s continental plates.

Lu’s Langshan discovery in 2015 – followed by more than two years’ investigation by his team at the China University of Petroleum and other institutions – revealed a spectacular, previously unknown event in Earth’s history.

At some point in the late Cretaceous period – from 100 million to 66 million years ago – North China and Central Asia collided and produced the Yinshan mountain range. At its peak, the Yinshan might have reached the height of the Himalayas, towering over a vast area of flatlands in the south.