China plans to build US$618 million Super Tau-Charm Facility, a particle collider to test modern theory of matter

- Scientists say key technologies are being developed to help test Standard Model of particle physics, with hopes of starting construction in three years

- Project chief scientist says proposed collider will help address questions such as ‘why the universe is dominated by matter instead of antimatter’

Key technologies for the 4.5-billion-yuan (US$618 million) Super Tau-Charm Facility (STCF) are now being developed, and construction can start in three years, according to scientists involved in the project.

Once operational, the collider will produce a huge amount of subatomic particles known as tau leptons and charm quarks to help better understand how they come together to form larger structures of matter.

“STCF will allow China to lead the world in tau-charm physics and related technologies for decades to come,” said project chief scientist Zhao Zhengguo, of the University of Science and Technology of China.

“It will also address cutting-edge scientific questions such as the nature of strong interaction, and why the universe is dominated by matter instead of antimatter,” Zhao told China Science Daily on Monday.

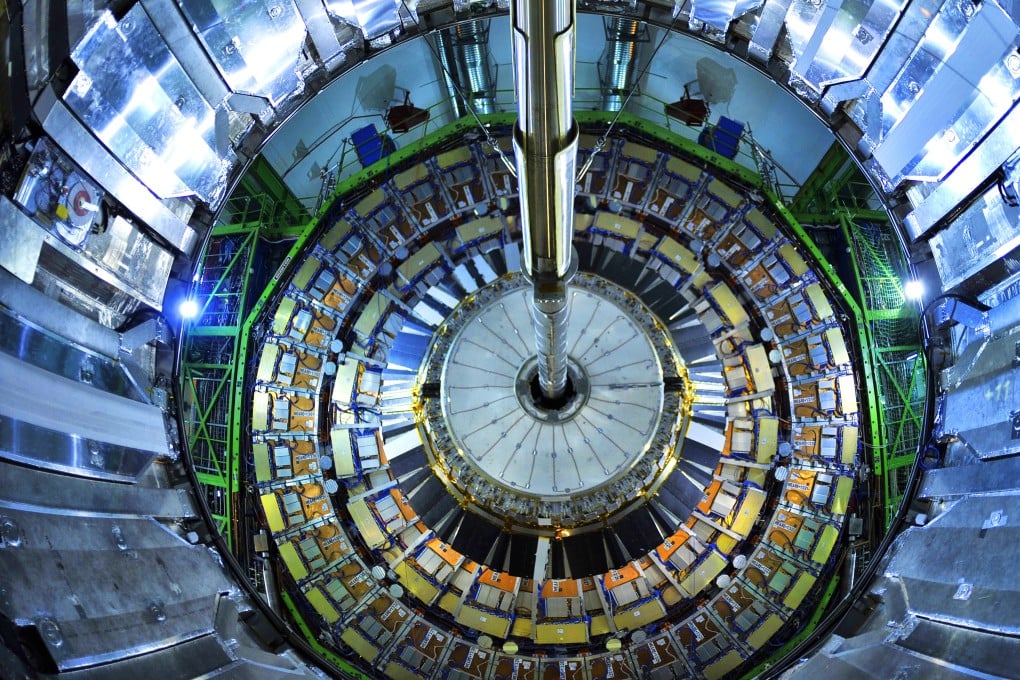

The trajectories, energies and electric charges of the subatomic particles are recorded by a so-called spectrometer to help scientists reconstruct the reaction processes.