How an ancient Chinese city used ‘collective power’ to divert the threat of floods

- The Neolithic Pingliangtai people built and maintained a drainage system with input from the whole community, researchers say

- The communal approach set them apart from the centralised hierarchies of the time

The team from China and Britain said the Pingliangtai people were part of a “collective social governance” society rather than a centralised hierarchy when they created the ceramic water management system 4,000 years ago in what is now Henan province.

The system operated mainly at the household and communal levels and would have required input from the whole community, according to the study published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Water on Monday.

“The construction and maintenance of the drainage systems and other public facilities were operated within a heterarchical social structure, which differs from the pyramidal power structure we are more familiar with,” said Zhuang Yijie, the study’s corresponding author and a researcher with the University College London’s Institute of Archaeology.

The Pingliangtai ruins were discovered in the 1980s and form the earliest well-planned prehistoric city in China.

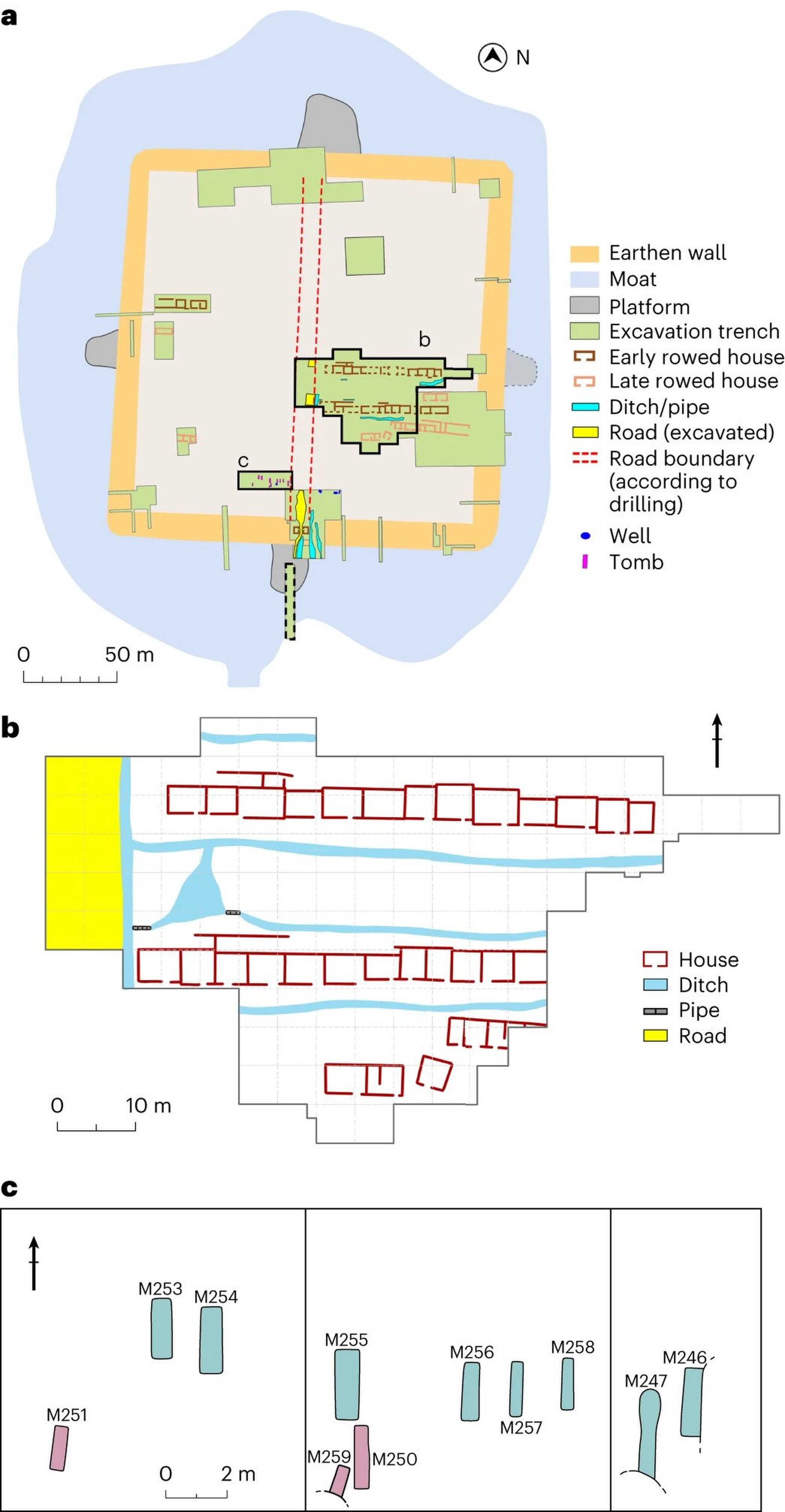

The square-shaped city was built on a five-metre-high platform, covered about 50,000 square metres (538,000 sq ft), and had a length of 185 metres (607 feet).

In 2020, archaeologists unearthed a number of ceramic drainage pipes and found the site had the oldest, most complete ancient urban drainage system.

The researchers said sediment cores indicated that before Pingliangtai and other settlements were built, the area was flat and low-lying, and periodically flooded.

Heavy summer rains could dump more than 500mm (19.6 inches) per month on the area, inflicting huge damage on the communities, they said.

To mitigate the floods during the rainy season, the Pingliangtai people developed a two-tiered drainage system.

The first tier was a series of drainage ditches that ran parallel with the houses and helped to divert water from the residential area.

The second-tier comprised a large number of ceramic drainage pipes, which could have required “careful planning and great effort probably involving different working groups of the entire community”, according to the study.

It would have been particularly effective at diverting water during the summer rains.

Zhuang said the Pingliangtai water system was a well-planned combination of ditches and drains.

“Ditches collected and discharged run-off at a relatively low time and labour costs, while ceramic drainpipes required greater efforts but were able to divert the water without affecting important ground infrastructure such as roads and earthen walls,” he said, adding the system was the product of “collective power”.

The collective approach was different from other communities during the Longshan period of the late Neolithic age, in which cemeteries showed a clear hierarchy, according to the authors.

“Such cooperative social governance on water with a pragmatic focus constituted a salient yet long-neglected part of the power structure and social governance on the Central Plains regimes in late prehistoric and historical times,” the authors concluded.

They also said the houses at the Pingliangtai site, as well as the cemeteries, showed no sign of clear social hierarchy or significant inequality among its population.