Global virus database GISAID pledges clarity on operations after Science article flags access issues

- Journal report says researchers’ access was cut off in response to criticism, which Global Initiative for Sharing All Influenza Data has denied

- ‘Totality of the facts raises important questions about GISAID and [its creator] Peter Bogner’, journalist pair who researched the article tell the Post

A key global virus database has said it is working to improve its governance and operations after a news investigation raised questions about transparency and access.

The Global Initiative for Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) was thrust into the spotlight after the journal Science reported on April 19 that researchers had been cut off from accessing the database. The report said the move was possibly retaliation for disagreeing with or criticising the initiative, which GISAID denied.

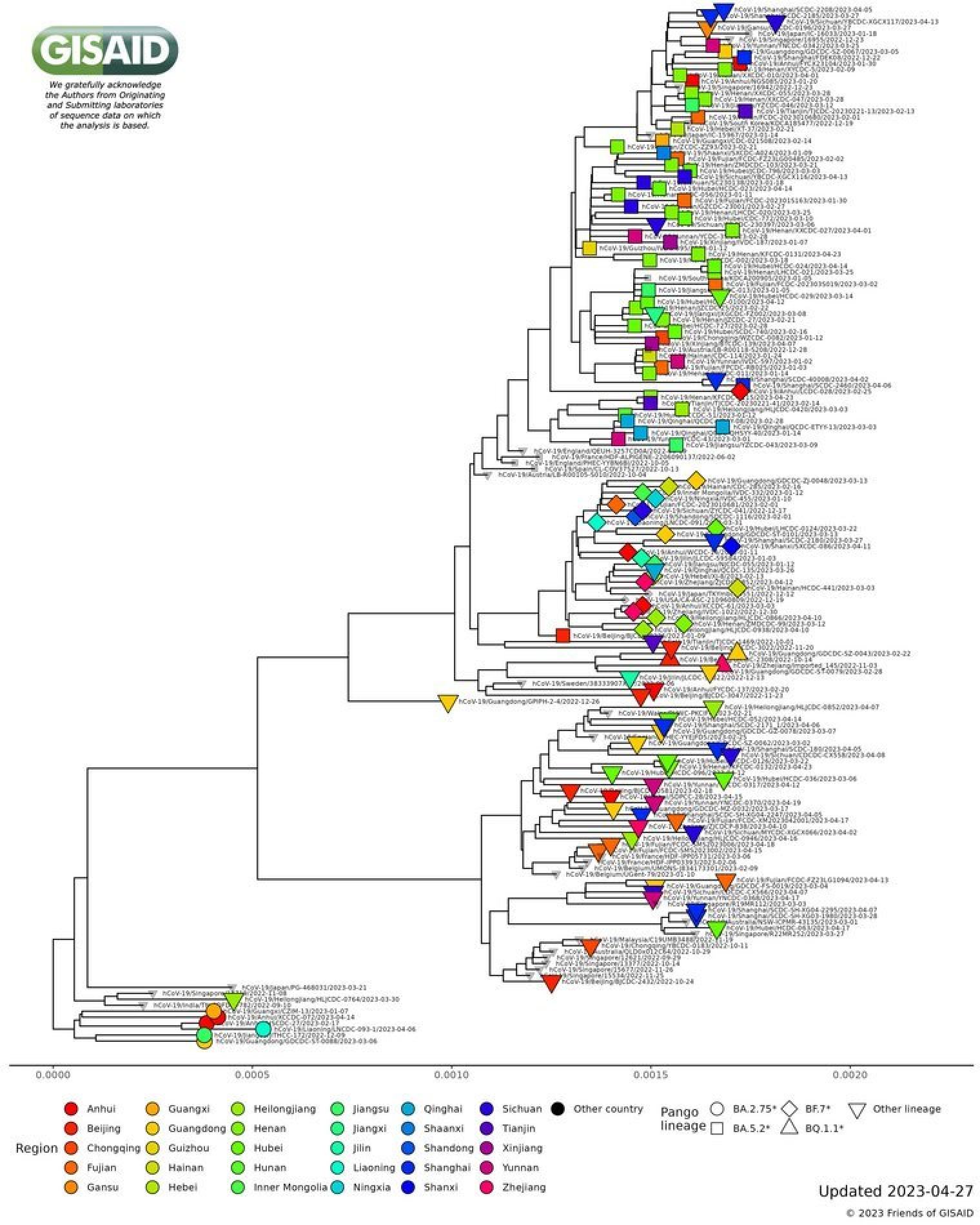

GISAID, launched in 2008, is widely used by scientists around the world to share information about the genome of flu viruses.

The database has been used to inform decisions about when and how to update vaccines and treatments for Covid-19 and the flu.

Following a months-long investigation, Science published detailed accounts of scientists temporarily losing access to GISAID’s data stream and receiving intimidating calls or messages after being critical of the platform.

In one instance, scientists at Scripps Research in California published a paper that suggested the first publicly shared Covid genome from a seafood market in the central Chinese city of Wuhan was published on a virology discussion forum. This contradicted GISAID’s claim that it was the first to share whole-genome sequences in early January 2020.

Science reported that on the day the paper was published, a researcher who works closely with the Scripps team received a message from a GISAID representative named Steven Meyers saying, “Good luck with getting further support” and “I warned you”.

The researcher later received angry phone calls from Meyers, according to the article.

The Scripps team lost access to GISAID’s data stream for around a week after the paper was published. According to Science, GISAID told the researcher that the access interruption was due to a technical hiccup.

China sends virus data to international database ahead of WHO meeting

In a statement to the Post on May 4, GISAID said it “has never taken any retaliatory action or imposed suspensions for any reason other than legitimate concerns around violations of our terms and conditions”.

It added that most of the temporary suspension cases were due to breaches of its terms of access, such as by obtaining data from GISAID and posting it elsewhere on the web.

“We remain committed to considering additional guardrails to ensure transparency in these matters. We also recognise that the growth of our platform means the measures once sufficient may no longer be adequate,” the statement added.

“As part of our steps to address governance and operating structure, we consider it a top priority to ensure a fair process for appeals and address the concerns of our users around suspensions.”

In the Science article, researchers shared their correspondence with a mysterious GISAID representative, whom they suspected was an “apparent alter ego” of the platform’s creator – Peter Bogner.

Jeremy Kamil, a virologist at Louisiana State University’s Health Sciences Centre Shreveport, said he had been in touch via email and on the phone with a representative named Steven Meyers, according to the article.

Kamil was reported to have become suspicious over time when his emails to Meyers were sometimes answered from Bogner’s account and when he received emails from Bogner about an issue he was talking to Meyers about at that very moment. Kamil said he had offered to visit Meyers in person but Meyers never seemed keen.

In December 2022, Meyers told Kamil that he would have a chance to meet Bogner, but Meyers himself would not be available. Kamil said he noticed Bogner had the same voice and accent as Meyers, and came to the conclusion that he had been in contact with Bogner – again something Bogner denied.

Another researcher who had been talking to Meyers over the phone also thought Meyers and Bogner shared the same voice after he listened to an audio clip, according to the article written by deputy news editor Martin Enserink and staff writer Jon Cohen of Science magazine.

“No one Science has spoken to in the virology community – including members of GISAID’s science advisory board – recalls ever meeting Meyers, or even seeing a picture of him,” they wrote.

“We feel the totality of the facts raises important questions about GISAID and Peter Bogner. That said, we felt that the alleged use of an alias was one of the strangest and most troubling parts of the story,” Enserink and Cohen told the Post.

The pair said they talked to more than 70 sources, including people who worked with or knew the founder and reviewed emails and documents to understand how the platform was founded, how the founder Bogner became involved, as well as his background.

They had also reached out several times to Bogner, GISAID’s media department, and the email address and phone number associated with Meyers, with a series of questions about Bogner’s background, Meyers, and GISAID’s financials and governance.

China to overhaul academic journals, boost profile of local scientific research

They received a response from GISAID media relations saying that they had responded to those inquiries over the years and “other inquiries – such as the ones on pseudonyms – border on the ridiculous such that no response is required”.

“We did not hear from Steven Meyers. We have not heard from GISAID since the story was published,” the writers said.

In its response to the Post, GISAID did not address the identity of Meyers.

“While we are incredibly proud of the work GISAID has done to help save countless lives, we recognise the need for the organisation to transform, and also to better communicate GISAID policies and implement some needed safeguards. GISAID is already working to improve that,” the initiative said in the statement emailed to the Post.

“Over the coming weeks and months, we will be announcing additional steps the Initiative will be taking regarding our work towards our governance and related practices, and look forward to sharing more information on these plans as they become available.”

While the scientific community acknowledged the key rapid data-sharing role GISAID had played in public health and scientific research into the coronavirus and flu viruses, improving its governance and transparency was critical, a globally renowned public health law expert said.

“After these revelations, trust in the governance of GISAID will be eroded. It is hard to trust an entity that acts in ways that are secretive and punitive,” Lawrence Gostin, a professor of global health law at Georgetown University, said.

“Healthy debate, even perceived criticism of global health resources like GISAID is very important. No scientist should fear retaliation if he or she criticises the governance of GISAID. That poses a chilling effect on researchers everywhere … We need global databases that have greater authenticity and legitimacy.”

“Ultimately, we may need more legitimate open databases, perhaps governed by the WHO or a respected global public-private partnership, such as GAVI, CEPI and the Global Fund,” he said, referring to a global vaccine alliance, a coalition that funds vaccine research and a non-profit foundation that aims to eradicate Aids, tuberculosis and malaria.

“We need highly respected institutions like the WHO overseeing open databases, with broad inclusive governance and high levels of transparency.”

Malik Peiris, chair of virology at the School of Public Health of the University of Hong Kong, said GISAID had been an extremely valuable resource since its inception.

China fines academic database owner US$12.6 million for antitrust violation

He said the database enabled rapid exchange of genetic information while offering protection for scientists who shared their sequencing results, unlike other platforms where other scientists could publish a paper based on uploaded data without necessarily crediting or recognising its original submitter.

He took avian and swine flu as an example. “It takes a lot of work to do the fieldwork to collect samples [from wild birds or pigs] before sequencing. Then it is important to share these sequences quickly for global public health.”

The requirement to acknowledge data contributors and cite GISAID in a paper was also proven important during the pandemic, especially for researchers in developing countries.

“In South Africa when [scientists] first discovered the Omicron variant, they immediately informed the world and made their sequences available on GISAID and other means. But then they were still able to publish very important papers on their sequences,” Peiris said.

He said after the initial rapid sharing stage, data on GISAID could be moved to other publicly accessible platforms, such as GenBank, the US National Institutes of Health genetic sequence database.

“Ideally, GISAID should be a short-term platform from where then everything becomes public and unrestricted. It gives a window of time for the people who generated the sequences to write papers or develop [products],” he said.

GISAID said it had no mechanism – nor a plan – to transfer data to public-domain archives, given the platform was already accessible to the public.

“When and how data generators share their data with the public will always remain their choice. Data generators around the world are well aware of their ability to release data [to] the public domain,” it told the Post.

“GISAID is the custodian of data, not its owner.”