China says tough measures in Xinjiang are to beat terrorism – why isn’t the West convinced?

- In 2014, President Xi Jinping launched strict new measures – ‘nets above and snares below’ – following a string of violent incidents

- Beijing’s narrative has been hampered by past downplaying of terrorist events for fear of stirring ethnic tensions or damaging the image of Xinjiang

International pressure against China over its Xinjiang policies has gained traction in recent months, with China criticised over the treatment of Uygur Muslims in Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. China has denied allegations of forced labour and detention. We look at the issues in this series.

Just months after the 2009 bloodbath and violent ethnic clashes that shocked the region and left more than 190 dead, Zhang, the region’s media savvy and somewhat charismatic new party chief, stepped in to replace his iron-fisted predecessor who had ruled the region for more than a decade.

In one month, Zhang lifted an eight-month internet ban in Xinjiang. In 2015, he became the first Xinjiang party boss ever to join Muslim groups to celebrate the Eid ul-Fitr marking the end of the Ramadan, the month when Muslims fast.

Yet despite Zhang’s pacifying approach deployed alongside his pledge of “no mercy to terrorists”, violent attacks continued to increase under his watch and reached beyond the region.

Zhang said he struggled to comprehend the attack.

“I was alone in a room and thinking about this quietly,” he recalled his reaction after he first heard of the attack. “How can there be such brutality?”

Xinjiang cotton dispute: human rights, sanctions and boycotts

The conundrum Zhang faced was hardly new for Beijing. The region of Xinjiang, home to more than 10 million Uygurs, among other ethnic groups, has been an intersection for different civilisations and a headache for Chinese central governments in Beijing for centuries.

In the years of violent attacks and ethnic clashes since the 1990s, Chinese officials have blamed separatism, first stemming from the independence of neighbouring former Soviet republics in Central Asia in the 1990s, and later global Islamic extremism, which was exacerbated by the Syrian civil war.

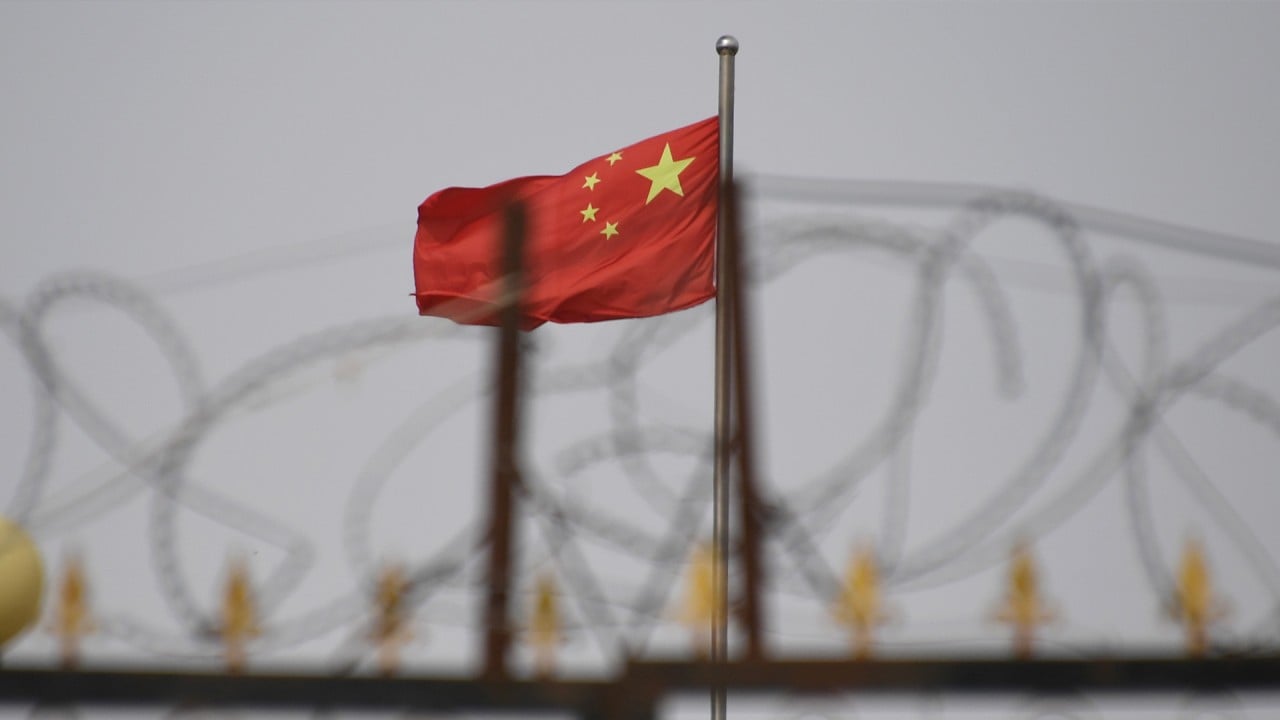

Since 2016, China has escalated its security measures in Xinjiang, including the extensive use of internment facilities, strict surveillance and intense political indoctrination.

These measures are believed to be a response by Beijing to terrorist attacks and ethnic clashes between 2009 and 2015, according to Raffaello Pantucci, a specialist on global terrorism with the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore.

“Violence became more frequent, and while it started in Nanjiang [in southern Xinjiang], you noticed how over time it spread across the region,” said Pantucci. “Watched from Beijing, I think the sense was that this was a problem which was growing -[it] had gone from the predominantly Uygur parts of Xinjiang to all over China and even abroad.”

Pantucci pointed to a wide range of violent chapters, including the 2013 attacks in Beijing that killed two and injured dozens, and an explosion and knife attack in Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi, on the same day in 2014 that President Xi Jinping wrapped up a trip to the region.

The two events were believed to have particularly angered Xi, who set a new tone for Xinjiang policies in a key meeting later in 2014, Pantucci said.

During that meeting, Xi called for a focus on fighting terrorism, mobilising civilians to support policing and setting up “nets above and snares below”. In the same month, China kicked off a year-long crackdown on terrorism in Xinjiang and beyond.

But the attacks and clashes went on.

“By 2016 there was a sense that whatever was being tried had not worked and something new was needed,” Pantucci said. “Zhang Chunxian could not deliver it, which is why he was booted out and Chen Quanguo brought in.”

With a set of policies now defined as genocide by Western governments, Chen Quanguo, who took the helm of Xinjiang in 2016, proudly reports zero terrorist attacks since 2017.

But Chen, who sits on the 25-member Politburo of the Communist Party, also became the most senior Chinese official to be sanctioned by Washington in 2020.

China’s treatment of Uygurs meets criteria of UN Genocide Convention: report

China has said the violent attacks and ethnic clashes were a result of planning and instigation by extremists outside its borders.

The existence of such threats were why harsh policies remained in place in Xinjiang, despite it reporting zero attacks since 2017, said Li Wei, a counterterrorism analyst at the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations in Beijing.

“The threats are not posed by only extremists from inside Xinjiang, but more importantly parties related to international terrorist groups outside China,” he said. “Such parties still have the capacity to infiltrate via the internet.”

Chinese officials said the group benefited from the rise of Isis, which turned parts of Iraq and Syria into training grounds for militants from Xinjiang. But Wu Sike, China’s then special envoy on Middle East affairs, said in 2014 that not all Chinese Isis recruits would return to China.

Some 114 people from Xinjiang were among the 3,500 foreign recruits to join Isis, as revealed by a defector from the jihadist organisation, according to 2016 studies by the Washington-based New America Foundation.

The number made Xinjiang the fifth-highest contributor to the group’s fighters – behind three areas of Saudi Arabia and one from Tunisia – which the study attributed to failures in Beijing’s own policies.

While there is well established evidence of Uygurs fighting in Syria for Isis and other groups such as al-Qaeda, there was no proof they were associated with attacks in China, Pantucci said.

“We have not seen any evidence of these groups directing those people back to China to launch attacks,” he said. “Isis/AQ are more focused on fighting on the battlefield in Syria/Iraq or against the West.”

Despite the threat Isis posed directly to Western governments, China’s efforts to justify its Xinjiang policies have largely failed in the West.

This was partly because the authorities had deliberately played down the severity of the attacks for years, said Li Wei, the Beijing-based expert on terrorism studies.

“The consideration then was to avoid affecting the image of Xinjiang, or to stir up tensions between ethnic groups,” Li said. “So many attacks were deliberately downplayed or not reported at all … and the effect has not been ideal.”

Beijing’s fear of ethnic tensions at that time was not groundless. After the knife-wielding attacks in Kunming railway station in 2014, Uygurs who lived in other parts of the country faced widespread discrimination and anger from Han Chinese.

Later that year Yu Zhengsheng, who was the fourth most senior official of the Communist Party, felt it was necessary to tell the Chinese public not to apply any label - such as terrorism - to Xinjiang.

But Beijing only published more details about many of these episodes after its Xinjiang policies were hit with a huge international backlash in the past two years. Some information about the 2009 riots was not released until a decade later, in a documentary by CGTN.

Why is Isis silent on China’s Uygur Muslims, when US alleges genocide?

While there have been groups similar to Xinjiang separatists in the past, the approach China is taking is in stark contrast to that taken in the West, Pantucci said.

“Xinjiang separatists are probably closer in ideology and outlook to ETA [the Basque nationalist group] in Spain or the IRA [Irish Republican Army] or loyalists in Northern Ireland,” he said, adding that these groups believed they were fighting to protect their community identity.

“Since Uygurs are Sunni Muslims this means that some of them find themselves attracted to the violent Islamist ideology which … appeals to their religious identity.”

But he said that in Europe members of potentially violent groups could be channelled into a more ordinary political approach through offering more political engagement and opportunity. He said there were no such signs in Xinjiang.