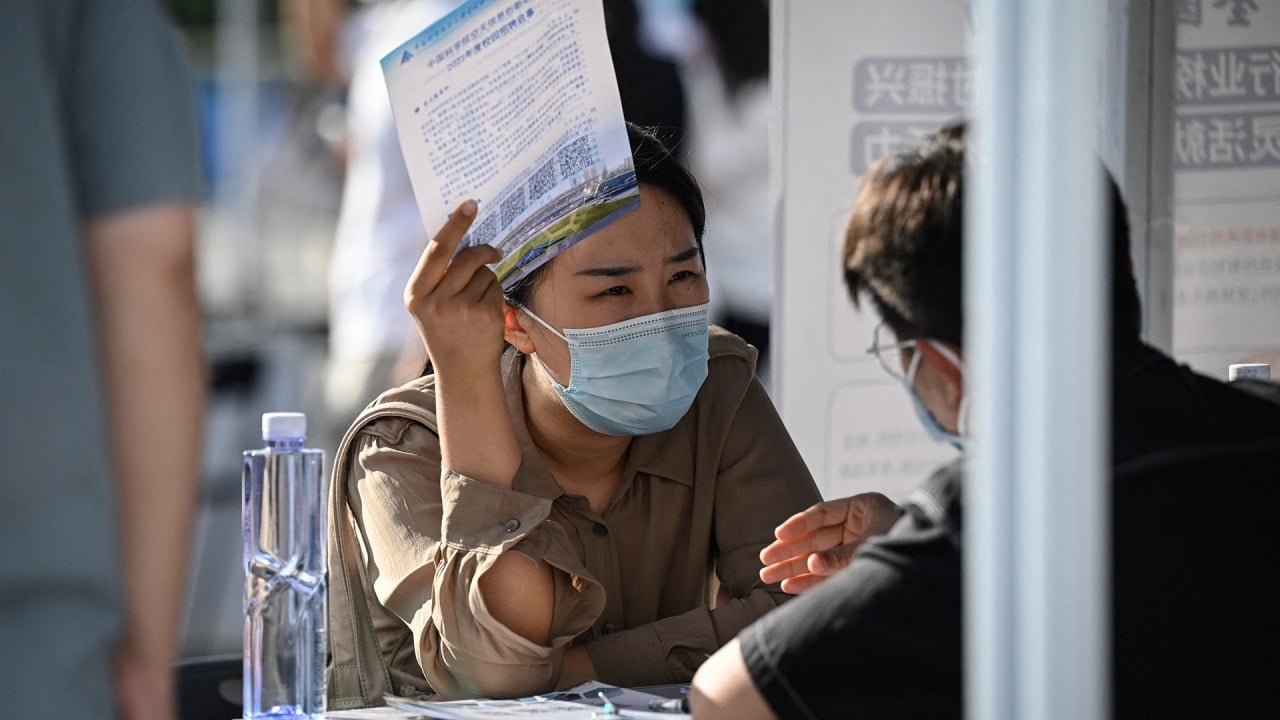

Covid pushed foreign students out of China. Will politics, red tape and poor job prospects keep them away?

- International student numbers have yet to bounce back since lifting of pandemic controls, but analysts are optimistic about a recovery

- However, many report dwindling enthusiasm for Chinese universities, citing geopolitical tensions, bureaucracy and employment concerns

New enrolments were at an all-time high in 2019 just before the pandemic hit but within a year that number had halved.

But prospective students appear to be cautious. They, along with present and former students in the country, say geopolitical tensions, campus interactions, red tape and gloomy employment prospects have dampened their enthusiasm for studying in the country.

‘Confusion’ over China’s spy laws could be deterring foreign students: academic

Amy Gadsden, executive director of China initiatives at the University of Pennsylvania, said that with shrinking foreign investment in the country, China experience was no longer valued as much as before.

“There’s not a sense that your job prospects are going to be greatly enhanced by having spent time in China in a way that was true 15 years ago.”

And for students who are interested in China from a national security perspective, they must balance their interest in spending time in the country with concerns that it could affect their ability to get a security clearance for future jobs, she added.

Chinese security agencies tell students studying abroad to beware of spy risk

Jack Allen, a British graduate of a two-year programme at the Yenching Academy of Peking University, said there were varying degrees of concern among his cohort that time spent in China might become a stumbling block for future job opportunities upon returning home.

“Even before applying, I remember reading articles about former Yenching scholars being questioned by the FBI about their studies upon their return to the US,” said the 25-year-old, who had considered a career path in public service.

“I did, in the back of my mind … worry about how my experiences would be looked at and received by future employers.”

He considered himself “lucky so far”, having secured a position as an events and communications executive for the British Chamber of Commerce in China after graduating last July.

But the risk has deterred many of his peers from setting foot in mainland China to study, with some choosing “safer and easier options” such as short-term visits or studying at language centres in Taiwan, Allen said.

He says the situation is paradoxical. At a time when in-depth knowledge of China is sorely needed, talented students are discouraged from gaining first-hand experience because of concerns that time spent in the country could be viewed negatively.

That was a dramatic drop from a high of almost 15,000 in the 2011-2012 academic year, according to data from the Institute of International Education, a New York-based non-profit sponsored by the US Department of State.

According to data released by the Chinese Ministry of Education, the number of international students freshly enrolled in higher education institutions peaked in 2019 with a total of 172,571. The figure dropped to 89,751 in 2020 when the pandemic hit before slowly climbing to 114,112 in 2022.

Chinese embassy cautions students after ‘interrogating, harassing’ at US airport

The fall was greatest in the number of American and South Korean, according to Richard Coward, founder and CEO of China Admissions, a platform that helps international students apply to universities in China.

Coward noted that when China opened its borders in January of last year, it was in the middle of the enrolment cycle, and many prospective students had already decided on their study destinations without considering China, since the country was closed for all of 2022 with uncertainty about when it would reopen.

“Students need on average about eight months before getting the initial spark of interest to [apply], and then some time before enrolling, so there is a time lag,” he said.

But he remained optimistic about the figures for the coming September as he said interest had gradually grown each month.

China urged to ease rules for scholars on overseas events and speaking to press

Jia Qingguo, former dean of Peking University’s international relations school, said geopolitics was not solely responsible for the plunge in international students’ interest in China since the number of Chinese students studying in Western countries remained strong post-pandemic.

Uncertainty over academic boundaries was one of the major factors behind the drop in foreign students, he said in a proposal submitted to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference during the advisory body’s annual meeting two weeks ago.

Specific regulations for implementing new laws related to foreigners had yet to be issued, “leading to some confusion”, he said.

A lack of clarity about the law and other difficulties in data collection are especially difficult for postgraduate students doing research in the country.

Gadsden said doctoral students had to find alternative research methods as China made it very difficult to collect data and conduct surveys and interviews – “all these things that are the cornerstones of academic work … that a generation of PhD students before them had been able to do”.

“China has increasingly strict data protection laws … so for researchers who are looking at large bodies of data to analyse, that’s harder. It’s also harder to do research collaborations.”

For Allen, the Yenching Academy graduate, bureaucracy was another headache, particularly in applying for a work permit.

When he and his classmates graduated in July last year, they had 30 days to obtain a job offer and another 30 to prepare documents, which for some required going home for a background check.

“For a lot of people, it was providing more documents than we’d already provided when we had been admitted,” Allen said. “It was very challenging to meet all those expectations so quickly after graduation, balancing it with study.”

Wang Huiyao, founder and president of the Beijing-based think tank Centre for China and Globalisation, noted that many of the elements required for international students to study in China – from flights and payment methods to courses and programmes – were still in the midst of resuming operations.

“For example, an international programme had been discontinued for several years, and its revival required the re-establishment of faculty and the development of new curriculums. It needs a process of recovery,” he said.

China’s youngest millennials deemed too old for jobs, and elder Gen Z are next

Anny Laghari, a 33-year-old from Pakistan who earned an MBA in China in 2017, applied to a PhD programme in management science, hoping to return to the country.

However, she is now hesitating about whether she should accept a full scholarship offer with a monthly stipend of 3,500 yuan (US$486) due to worries that she might not land a job at a Chinese company after graduation.

“If I continue PhD [studies], that would take five to six years, and I would be [around] 40 years old then,” she said.

“I’m considering all the reasons and I’m not sure if [taking the offer] could bring any positive change in my future,” she said.

“I feel really bad. I really wanted to stay in China for a long, long time. I had a lot of memories there. I liked living there. I hope in the future there can be [changes] for people like me.”

Hospitality professional Muhammad Shahid, 25, who is from Pakistan but lives in Dubai, left China in January after quitting a master’s degree programme in the southwestern city of Chengdu after one semester.

“It was like wasting my time only taking classes and [doing] homework,” said Shahid, who studied enterprise management. “They focused more on the academic side than skills. No new things.”

“In class, we were sitting like strangers,” he added. “We had some presentations – but Chinese students with Chinese and international students with international ones. No learning, no sharing ideas … I [got] fed up with these kinds of things.”

He completed undergraduate studies in Chengdu from 2017 to 2021 at Sichuan University and loved his life there. But when he headed back to China last year, he found the student visa application more difficult than before.

“A lot of requirements [were added],” he said. “And at the Chinese immigration [it was] completely complicated in terms of technology.

“China is more advanced than other countries but when it comes to this, [it was still] far away. This is the ground reality.”

China’s technical expertise touted as new vehicle for progress on belt and road

The number of Americans studying in China is expected to remain relatively low, but there is greater interest from students from Southeast Asia and belt and road countries, according to Wang with the Centre for China and Globalisation.

Ghezio Rosario Ribeiro, 21, from East Timor in Southeast Asia, is studying for a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering at Beihang University in Beijing.

Growing up, he saw China emerge as a leader in nation-building, which motivated him to apply to study in a country that he said provided “the best education”.

The 21-year-old said his country still needed human resources, especially in construction and design.

“I would be very happy to return to my country and work there [after graduation]. Considering a lot of Chinese companies are [there], my Chinese skills will be a bonus point for me,” he said.

He said he enjoyed his life in China, even before the lifting of Covid restrictions, but he wished the scholarship offered by the Chinese government were higher as he had to work part time to cover the cost of living in Beijing despite the scholarship’s 2,500 yuan monthly living allowance.

According to Ribeiro, a group of more than 100 students signed and submitted a proposal to his university’s international student office to ask for an increased stipend.

Not spy devices claims university as students object to stress-causing cameras

While geopolitical tensions have weighed on the decisions of some prospective students, many with experience in the country say the benefits of spending time in China outweigh the negatives.

Allen, the Yenching alumnus, said his first-hand experience in the country enabled him to “push back against a simplistic vision of a monolithic nation”, and to hear a diverse set of perspectives from China.

“There are very few questions that don’t have a China angle or dimension to them,” she said. “We do ourselves a disservice when we don’t dive into that and study that.”

“It takes more than our leaders at the highest levels, making statements about the importance of education,” she said.

“It takes the work of universities, faculty, administrators, people who do this for a living like me, to create the opportunities and to show and explain why it’s important to go and why it’s valuable to go.”