Chinese investment in Cambodia is bringing Phnom Penh closer to Beijing – and further from the EU

- The Southeast Asian nation signed at least nine deals with China last week on the sidelines of the second Belt and Road Forum

- These investments have seen growing anti-Chinese sentiment, and some analysts say it is likely political obedience to China will include military access

Besides the defence funding, China agreed to up its imports of rice from 300,000 tonnes to 400,000 tonnes, and announced plans to launch a second phase of development in the coastal Sihanoukville province where it has already built over 100 casinos and dozens of hotels and resorts.

We are siblings who share a single future

Beijing also promised China would help Cambodia mitigate losses from possible European sanctions over human rights and other violations such as the pre-election arrest of main opposition leader Kem Sokha and the dissolution of his National Rescue Party.

China’s relationship with Asean under scrutiny as Suu Kyi makes first visit to Cambodia

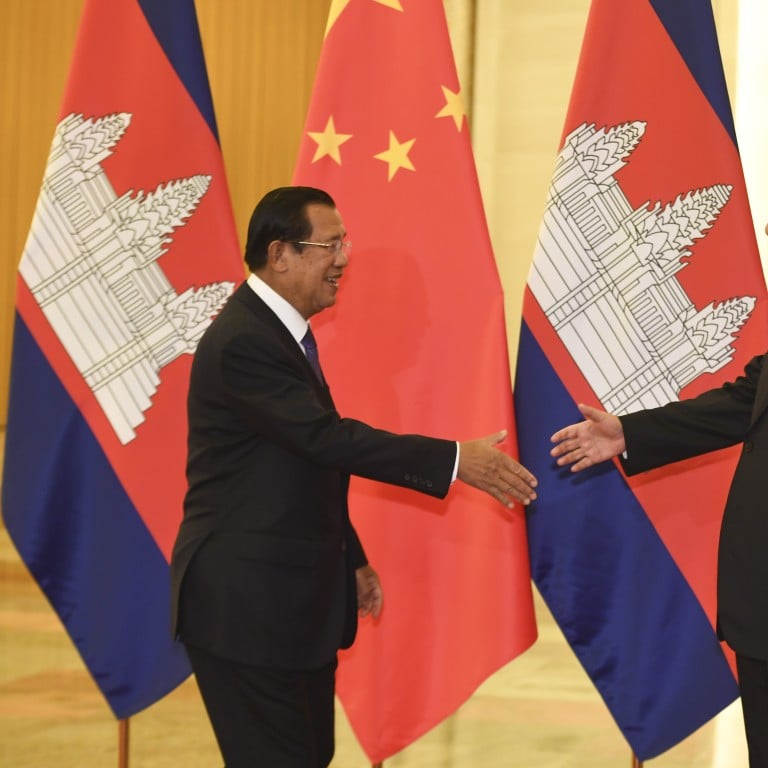

“As comprehensive strategic partners and ironclad friends, we are siblings who share a single future,” Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen said of China’s relationship with Cambodia in a Facebook post following the forum.

To Astrid Noren-Nilsson, political scientist and lecturer at Lund University in Sweden, this is “a clear signal to the EU from China that it will step in where the EU pulls out”.

In February, the EU began the process of revoking a trade deal it signed with Cambodia, a de facto one-party state. Known as the Everything But Arms (EBA) deal, it allows underdeveloped nations to export all goods other than weapons without quotas or duties.

The potential withdrawal – prompted by Cambodia’s domestic political crackdown – will particularly impact its robust US$5 billion garment sector, which employs around 750,000 people. It is expected to cost the Southeast Asian country about US$676 million a year, according to a letter from Cambodia’s commerce minister to Hun Sen.

Separately, the EU imposed protectionist tariffs on rice coming from Cambodia, starting at US$200 per tonne of rice, with the rate slightly lowered each year for three years. In the past five seasons, rice exports from Cambodia to the EU grew by 89 per cent, reaching 270,000 tonnes in 2018.

Noren-Nilsson, who specialises in Cambodian politics, said China’s support of Cambodia meant Hun Sen might believe he no longer needed to make any concessions to avoid losing the EBA.

“China’s commitment to Cambodia certainly makes the prospect of major concessions even more remote,” she said.

Chinese tourists win, poor Cambodians lose with US$4 bn casino in Phnom Penh

In addition to the deals signed, Hun Sen reportedly asked a Chinese firm to partner Cambodia’s Royal Group to develop the country’s railways; the China Huaneng Group announced plans to develop a 200-megawatt solar power project in Cambodia; and the government signed a preliminary contract to develop a 5G network with Chinese telecommunications megacorporation Huawei.

China is the largest investor in Cambodia by a wide margin, pumping in US$12.6 billion since 1994, with the bulk of it coming in the last few years. China invested US$3.6 billion in 2016, according to the Council for the Development of Cambodia, a figure that nearly doubled to US$6.3 billion a year later.

Greg Poling, a fellow at the Washington-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies, said more aid and investment from China was “to be expected” as Cambodia fell deeper into China’s “orbit”.

“Beijing has been increasingly free with aid, investment and debt forgiveness in exchange for Phnom Penh’s political obedience and access for Chinese companies,” Poling said, adding that it was “increasingly likely” this political obedience would include military access.

Joshua Kurlantzick, senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) in New York, said the benefits of this strategy for China included a solid relationship with Hun Sen; closer ties to the military which would be “critical” in a succession event; an advantage over Cambodia’s previous patron state, Vietnam; and continued economic investment.

Is Cambodia’s Koh Kong project for Chinese tourists – or China’s military?

In March, a state-owned construction company China Road and Bridge Corp also committed to building Cambodia’s first expressway. The US$2 billion project, which will be built debt-free and paid for in future tolls, will connect the capital of Phnom Penh to coastal tourist destination Sihanoukville, 190km away.

The seaside resort town has been radically transformed by Chinese development in the past few years, boasting over 150 casinos while dozens of construction cranes still dominate the skyline.

Hun Sen claimed the next stage of development in Sihanoukville will create 800,000 jobs, a massive increase from the 200,000 created in the first stage, signalling that the rampant construction is just getting started.

The Cambodian government also granted a Chinese company a 99-year lease in Koh Kong province on 20 per cent of the country’s total coastline.

While many property owners and other locals are benefiting from the economic investment, there’s a growing sense in Sihanoukville and Cambodia at large that the country is being sold to the Chinese, prompting backlash and resentment.

In January 2018, Preah Sihanouk provincial governor Yun Min expressed frustration over growing crime and public disorder in Sihanoukville associated with the Chinese influx. In a letter to the Interior Ministry, Min also bemoaned rising rents, the inability of local businesses to compete with Chinese companies, and the oversaturation of Chinese labourers in the construction sector.

The development has also come under scrutiny for its environmental damage and for provoking violent land disputes as property costs skyrocket.

Cambodian PM welcomes extra US$600 million in aid during visit to Beijing

Facing backlash from a number of countries in the region over the perception that the Belt and Road Initiative serves Chinese foreign policy interests more than the host nations’ development needs, Beijing is addressing certain downsides to the project.

At the opening of the Belt and Road Forum, China’s Finance Minister Liu Kun pledged to “build up a debt-sustainability framework to prevent and resolve risks”, while Xi promised to combat corruption.

“Beijing does seem to be becoming more sensitive to complaints,” said Kurlantzick from the CFR, but it remains to be seen whether material changes will occur.

He said the issue of local resentment could theoretically undermine China’s own strategic objectives.

“But for that to happen, I think the issue of China’s influence in Cambodia would have to be catalytic in a political contest in Cambodia,” Kurlantzick said. “Without any real elections or prospect for them in Cambodia, I’m not sure what the force would be that altered Cambodia’s relations with China.”