Are automatons once again the face of luxury watches and clocks?

Look closely into the window of watchmaker Jaquet Droz’ Charming Bird timepiece and there’s something small and rather marvellous happening: a tiny bird spins on its axis, chirping and flapping its wings. Behind this scene, however, even tinier sapphire tubes and carbon pistons pump away to make it all happen.

The piece is part of the company’s Automata collection. The latest piece, launched this spring, is the Loving Butterfly. Another piece is set to be unveiled in China at the end of the year. Each is a watch, but then each is also something more than that: a demonstration of the ingenious use of mechanical movement not to regulate time, but create animation.

“An automaton prompts a sense of wonder,” says Jaquet Droz’ CEO Christian Lattmann.

“They’re much sought after by connoisseurs, even though most people don’t think of clockwork’s potential much beyond watchmaking.

“It’s hard to imagine just how much work goes into these pieces – the miniaturisation of the mechanism is a real challenge. But track the value of these pieces in the auction market and they’ll certainly reach new highs.”

While automatons cover a huge variety of types, interest in historic and complex mechanical pieces is increasing, says Daryn Schnipper, chairman of Sotheby’s worldwide watch division. Two years ago, its “Swiss Mechanical Marvels” auction sold a private, single-owner collection of musical and singing bird automatons from the 18th and 19th centuries, with 21 pieces valued at US$2.3 million.

There’s a fluidity to automatons that you still can’t get with modern robotics, and a human element in this marriage of art and science that a computer chip doesn’t offer

Prices are rising, too. A Gustav Vichy Monkey Harpist automaton, auctioned this spring by New Jersey’s Bertoia Auctions, was expected to sell for about US$3,000; it was bought for US$7,200.

“Automatons were the ultimate luxury toys of their day,” Schnipper says, explaining their attraction to collectors. “It’s difficult today to wrap one’s head around the level of sophistication necessary to produce these mechanical objects back then. They weren’t just created without the aid of computers – they were early computers in their own right.”

Indeed, could there be renewed demand for automatons precisely because of the concomitant surging interest in robotics – sparked, in part, by the huge worldwide popularity of television series such as Westworld and Humans?

Among the more famous automatonsin history were those parlour entertainments that shocked and amused audiences – typically at court – by mimicking human behaviour: dolls, for example, that played the harpsichord, drew precise pictures, or told your fortune.

Ellen Rixford, the author of Figures in the Fourth Dimension: Mechanical Movement for Puppets and Automata, believes that today’s popular culture is inspiring a reappraisal of this art form, which goes back centuries.

“The difference is that, unlike today’s robotics, automatons are accessible,” she says. “People can grasp the mechanics of gears and cams, even play around with building a basic automaton themselves. Of course, the great automatons of the 18th and 19th centuries were complex and so fragile, and not helped by the fact that their makers tended to be secretive about their methods. Not many automatons of that period survived: for some makers only their drawings [remain]. That means the pieces that have survived can be extremely valuable and collectible.”

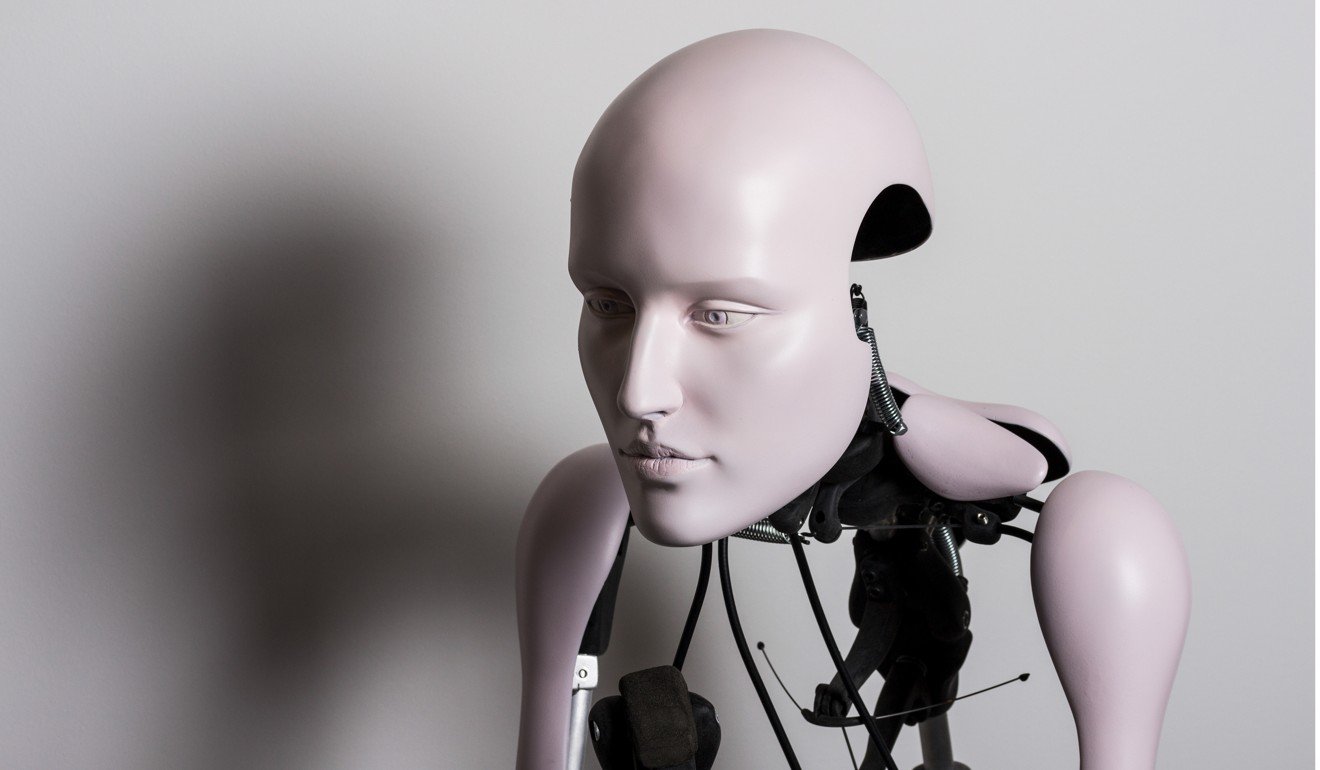

Turkey’s Server Demirtas, who puts a more modern, hi-tech spin on automatons, is among the more striking artists to be working with Busser: his one-off pieces include a flower that recoils and folds when an attempt is made to smell it, and humanoid sculptures that appear to breathe. This year’s display of mechanical sculptures, Desiring Machines, includes a small humanoid figure leaning and shifting its weight restlessly against a wall.

“It’s the fluidity of movement in these automatons that impresses – as with automatons historically, the people who see them tend to feel slightly unhinged by them,” Busser says. “It’s why the simpler in look they are, the more impact they have on viewers.

“They still give that sense that we’re playing god. It’s Promethean. Show someone a watch movement, then show them a clockwork animal and you get a very different reaction. And that’s impressive for such an old discipline.”

Tech becomes an art form as automatons enhance luxury timepieces by MB&F, Van Cleef & Arpels and Jaquet Droz