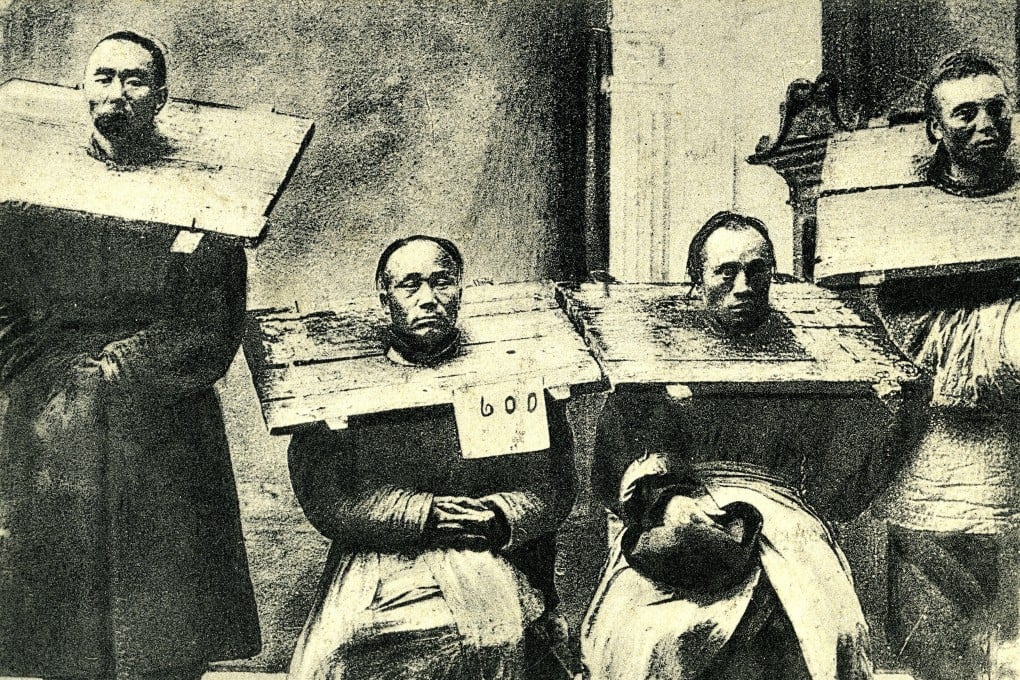

Reflections | Crime and collective punishment: in imperial China, you could be killed for your family’s misdeeds

- Every misdeed has consequences, as those living under Qin rule well knew – only the king, and later emperor, were spared

- An official who committed a capital crime would be killed with members of three families related to him

Such collective punishments are rare nowadays but were common in the past. Collective punishment is most associated with the state of Qin during the Warring States Period (475-221BC) and the subsequent Qin dynasty (221-206BC). The adoption of its harsh provisions were among the sweeping reforms implemented by the legalist thinker Shang Yang (390-338BC), and covered all aspects of Qin politics, society and economy, ultimately helping to make Qin the strongest state that unified a fragmented Chinese nation.

The Qin’s collective punishment applied to everyone: government officials, military men and the common people all suffered its severe punitive consequences. Even members of the aristocracy and nobility were not spared; only the king, and, later, the emperor, were exempted.

An official who committed a capital crime would be executed together with members of three families that were related to him. There are different interpretations of which three families these were. They could the families of the official’s father, mother and son; or the families of his father, brother and son. In subsequent centuries, this principle expanded to include members of nine families.

Officials who reported the crimes of their superiors would be rewarded with the latter’s rank and pay, but those who were found to have made false accusations would be severely penalised. Later on, collective punishments of individual officials would also extend to their subordinates. For heinous crimes, the staff of entire bureaus could be executed, but ordinarily they would be demoted or dismissed for a lesser misdemeanour.

The smallest units in the Qin army were squads of five men. If one behaved in a way that could jeopardise the unit, the army or the state – such as cowardice in battle, desertion, treason, and so on – the other four comrades would also be punished.