Then & Now | The disappearing language of Chinese hand signals, once shorthand for Buddhist monks and discreet dealings

Invented to expedite communication for travelling Buddhist monks, hand gestures eventually evolved into a less honourable means of communication and today are largely the preserve of mobsters

A once-commonplace aspect of Chinese life, which has largely – but not entirely – disappeared, is the use of hand signals. They evolved with the popularisation of Buddhism and spread from India into China more than 2,000 years ago, eventually transforming in form and purpose.

Mendicant monks in China, as in other parts of Asia, could travel great distances in relative safety on religious pilgrimages, relying on food and lodging at local monasteries along the way. Typically, the only major problem they encountered was communicating with each other, or any laypeople they encountered, owing to language differences.

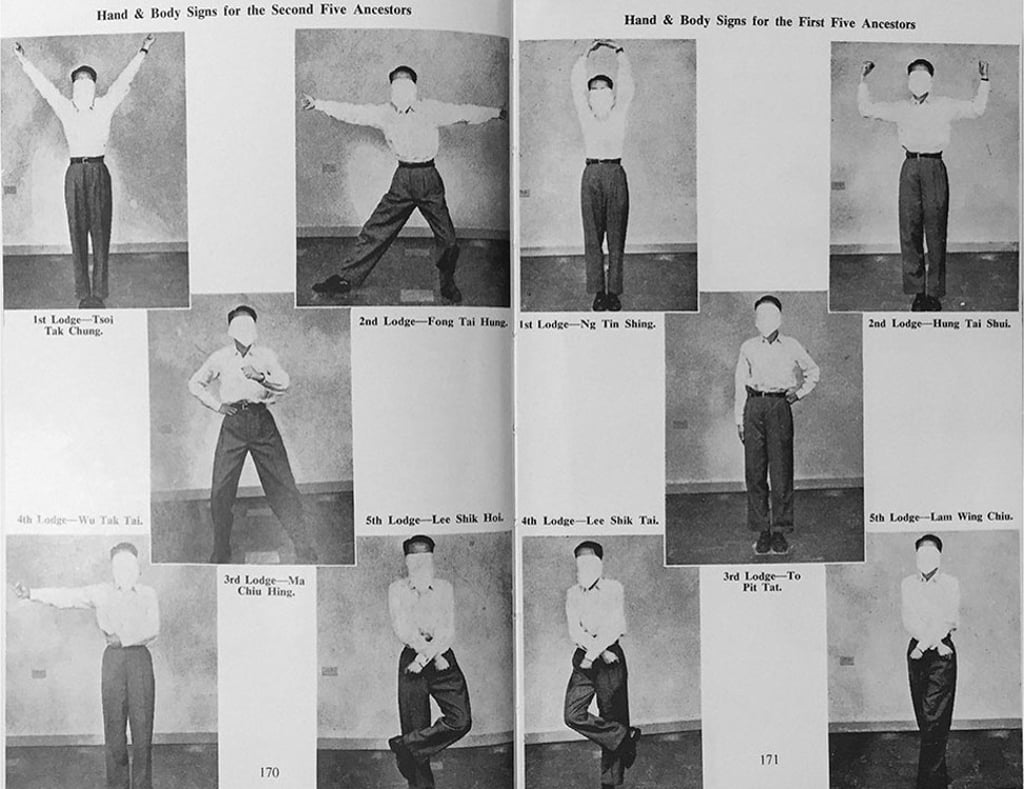

Mutually comprehensible hand signals were essential, and a complex non-verbal system, based on the Buddhist mudras, or symbolic philosophical gestures, gradually evolved. The sight of robed monks waving their hands at each other in various gesticulations, aided by intermittent smiles, grunts and random words, became a familiar one, especially around Buddhist pilgrimage sites.

As a method of communication, Buddhist hand signals functioned much like Latin, which formed the common language of the educated classes in medieval and early-modern Europe, essentially excluding everyone except priests and monks. Through basic spoken Latin, Germans could communicate with Spaniards, Swedes with Neapolitans, as well as each other, wherever they met. In Catholic Europe, ordinary people knew only a few phrases, mostly responses to the Mass. A passing villager, on hearing two monks babbling away in what he recognised as Latin, would know only that it was an arcane priestly language, and understand virtually nothing else.

Likewise, Buddhist lay people in China knew some of the mudras by sight. As in Europe, criminals or political dissidents could easily disguise themselves as wandering monks. When clad in a uniform robe, with shaven head, shoulder bag and begging bowl, one monk looked much like any other, making it a useful disguisefor anyone trying to evade detection. At a time when most people (especially in rural areas) seldom travelled more than a few miles from home, a passing “monk” on a pilgrimage was a plausible figure who attracted little notice.