Reflections | Why Chinese have multiple names, and the many monikers of Sun Yat-sen

Known as the ‘father of modern China’, among other things, Sun Yat-sen took the custom having many names to extreme levels

My name on my Singapore identity card is Wee Kek Koon (Huang Kequn). “Wee Kek Koon” was given to me by my grandmother and parents while “Huang Kequn” was the name the city state foisted on me when I was in primary school. In the 1980s, the government decided that all Chinese names would be rendered in pinyin because the Singaporean and Malaysian practice of romanising ethnic Chinese names according to the pronunciation of one’s native dialect (Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, Hainanese and so on) was seen as confusing.

The policy was dropped after a few years, but for those of us with the alias tacked on to our identity documents, the alien name has stuck. I had it removed from my passport, and since then the number of questions I am asked when crossing borders has greatly reduced.

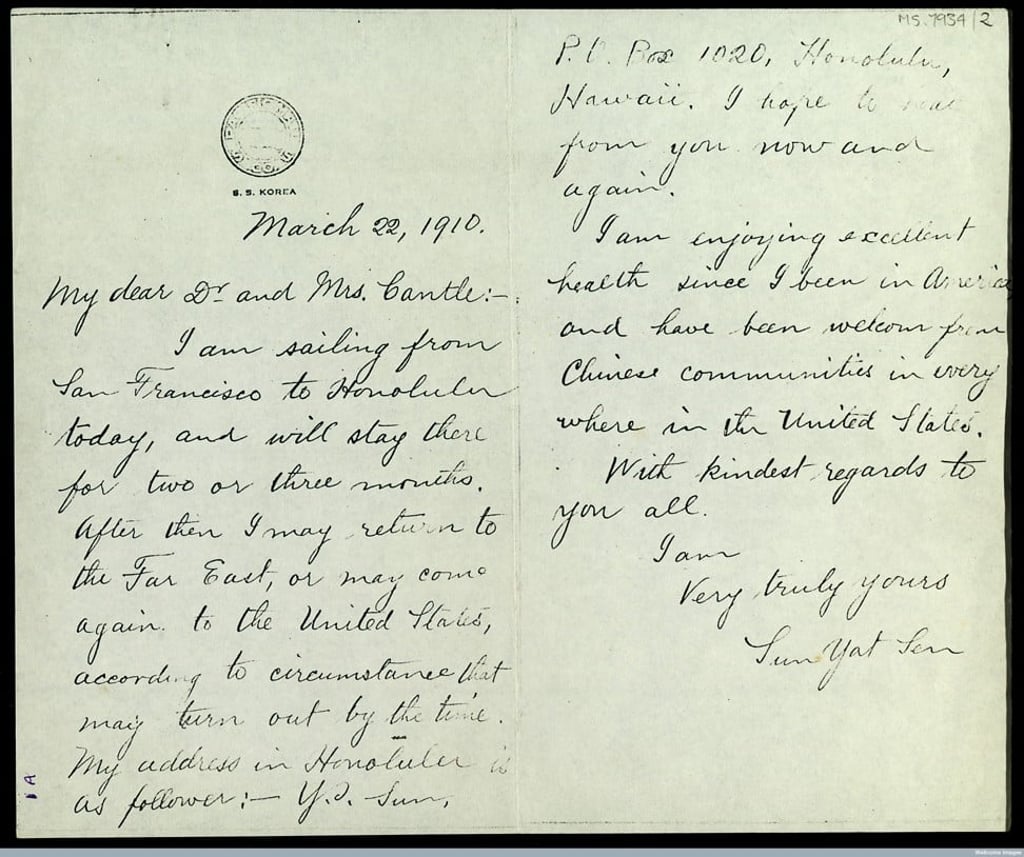

For people of Chinese descent, however, having more than one name was common. Consider Sun Yat-sen, the “father of modern China”, who was known by multiple names (most of which are rendered in pinyin here for convenience). His official name, taken on when he started school, was Wen (“literary” or “scholarly”), which remains a popular character for names of both Chinese men and women. Sun would have signed official documents as “Sun Wen”, and many extant calligraphic works of his bear this epithet.

As a child, his parents and other family members called him Dixiang (“likeness of a deity”). Sun also had a “genealogy name”, Deming, which would be registered in the family’s genealogical records. Like many educated people of his time, he had a courtesy name – Zaizhi – with which he would be addressed by associates and acquaintances. When Sun converted to Christianity in Hong Kong in the 1880s, his baptismal name was Rixin (“daily renewal”), from a passage in the Confucian classic The Great Learning. Soon afterwards, his pastor changed his name from Rixin (pronounced “yat san” in Cantonese) to Yixian (pronounced “yat seen”), and it is by this name – “Sun Yat-sen” – that he is most well known to Westerners.

Wanted by the Qing government for his subversive republican politics, Sun went into hiding in Japan, where he took on the pseudonyms Nakayama Kikori and Takano Nagao. The Chinese characters of the name Nakayama (“middle mountain”), pronounced “zhong shan” in Mandarin, became part of the name by which he is universally referred to by Chinese speakers: Sun Zhongshan. Although he never referred to himself by this name, this name was so popular that when he died in 1925, his birthplace near Hong Kong was officially renamed Zhongshan.

Mercifully, most people of Han Chinese descent today go by far fewer names than Sun did.

Apart from Kek Koon, I have another moniker, my initials K.K., which is what most friends from outside Singapore and Malaysia call me. On a recent trip back home to Singapore, I went to the relevant government agency to inquire about having the additional name on my identity card removed. By the end of the year, “Huang Kequn” will have been expunged from my records.