- Phuong Canh Ngo was jailed for life in 2001 for masterminding the 1994 murder of John Newman, a New South Wales politician, but was he guilty of the crime?

As a nation born from a penal colony, Australia has a long history of colourful and loathed criminals, but few are more reviled than Phuong Canh Ngo, a former Vietnamese refugee who holds the unenviable title of being the country’s first and only convicted political assassin.

In June 2001, a supreme court jury found that Ngo had masterminded the murder of John Newman, an MP in the state of New South Wales. Newman was shot dead in front of his fiancée, Lucy Wang, outside the couple’s home in Cabramatta – a suburb within his electorate in the Fairfield local government area of western Sydney – on the evening of September 5, 1994.

Home to the largest migrant hostel in the state before its demolition in the early 1990s, Cabramatta has long been a nesting ground for migrants from all walks of life. But the arrival of boatpeople in Australia after the end of the Vietnam war, coupled with a massive jump in migration following the Southeast Asian country’s relaxing of departure restrictions in 1990, transformed Cabramatta into a thriving Asian community nicknamed “Little Saigon”.

By 1995, a third of the suburb’s population identified as Vietnamese, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Today, the main thoroughfare of John Street resembles a historic Chinatown, with a large crimson-coloured Chinese gateway celebrating liberty and democracy, bronze lion statues symbolising strength and piglet sculptures representing prosperity. Asian grocers sell frozen durian and dragon fruit from Indonesia.

There are gold traders, thrift shops, haberdasheries galore, and Vietnamese restaurants that dish up the best pho and banh mi south of the Mekong Delta.

But things were not always rosy in Cabramatta. Freed from the strict hierarchies that would normally contain their rebellious streaks back home, scores of Vietnamese-born teenagers found themselves on the wrong side of Australian law.

By the 1990s, Cabramatta had become a no-go zone for law-abiding Australians: heroin was sold openly, users overdosed on the streets and Asian gangs such as the notorious 5T ruled the roost. The drug problem was so severe that police dubbed the train between Sydney city and Cabramatta the “junkie express”.

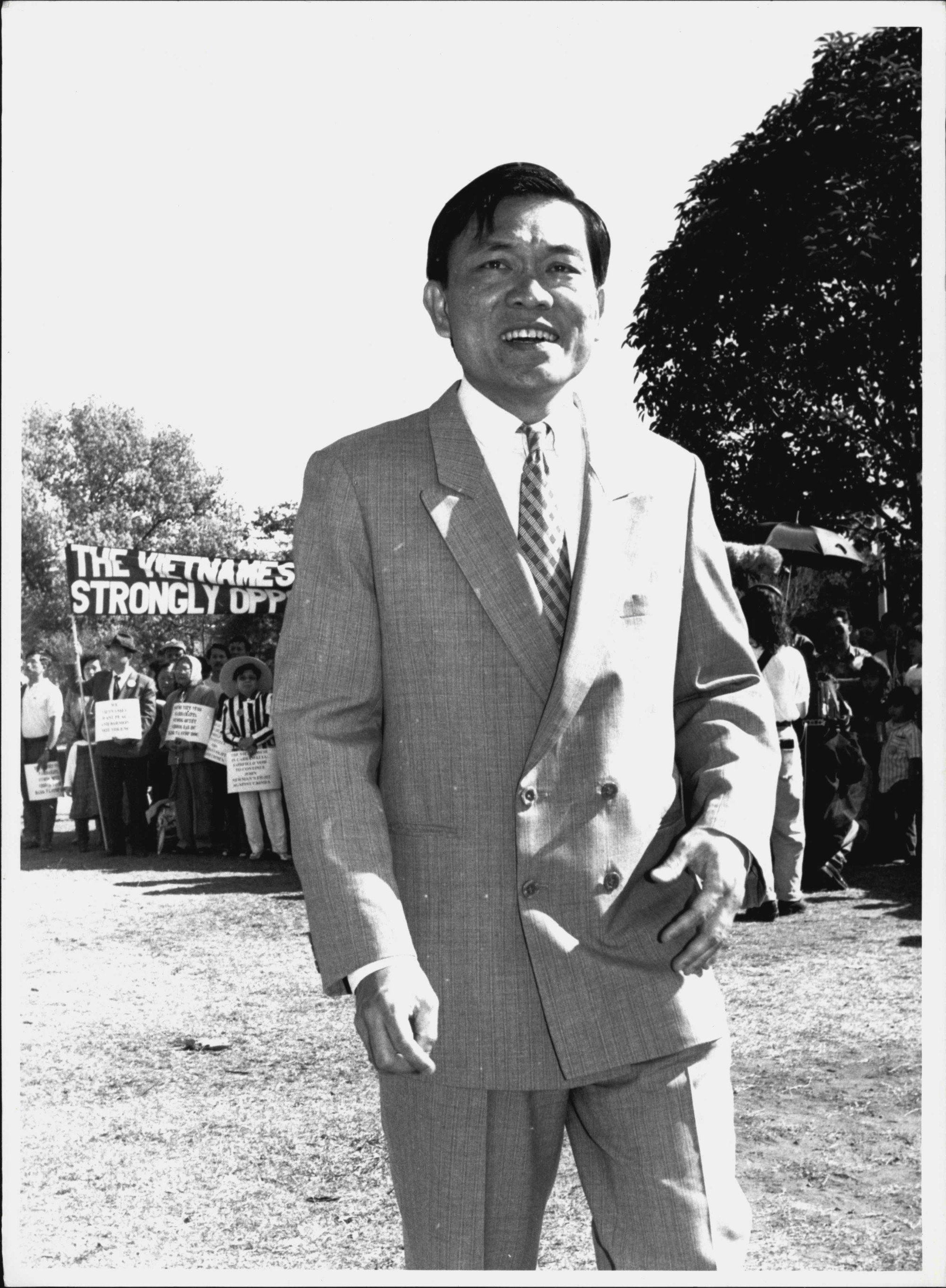

MP John Newman pulled no punches as to who was to blame. “The Asian gangs involved don’t fear our laws but there is one thing they do fear: possible deportation back to the jungles of Vietnam because frankly, that is where they belong,” he told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation at the time.

Newman held particular disdain for Ngo, who he believed ran illegal gambling, heroin and money-laundering operations at Cabramatta’s Mekong Club, of which Ngo was honorary president and which was often patronised by members of 5T.

Nick Kaldas, then-head of the New South Wales homicide squad, who led the investigation into Newman’s murder, concurred.

“In the morning, Ngo would sit on the board of the Area Health Service, go to council meetings and present a respectable veneer,” he told The Daily Telegraph in 2014, referring to Ngo’s role in local government. “At night, he sat in his headquarters, the Mekong Club, and controlled the 5T gang.

“When Ngo was arrested and charged, hundreds of people from Cabramatta signed a petition pleading with the judge not to grant him bail, which is an example of the fear he instilled in many. By ridding the Vietnamese community and Cabramatta of Ngo, the area became the colourful piece of multicultural Sydney it is today.”

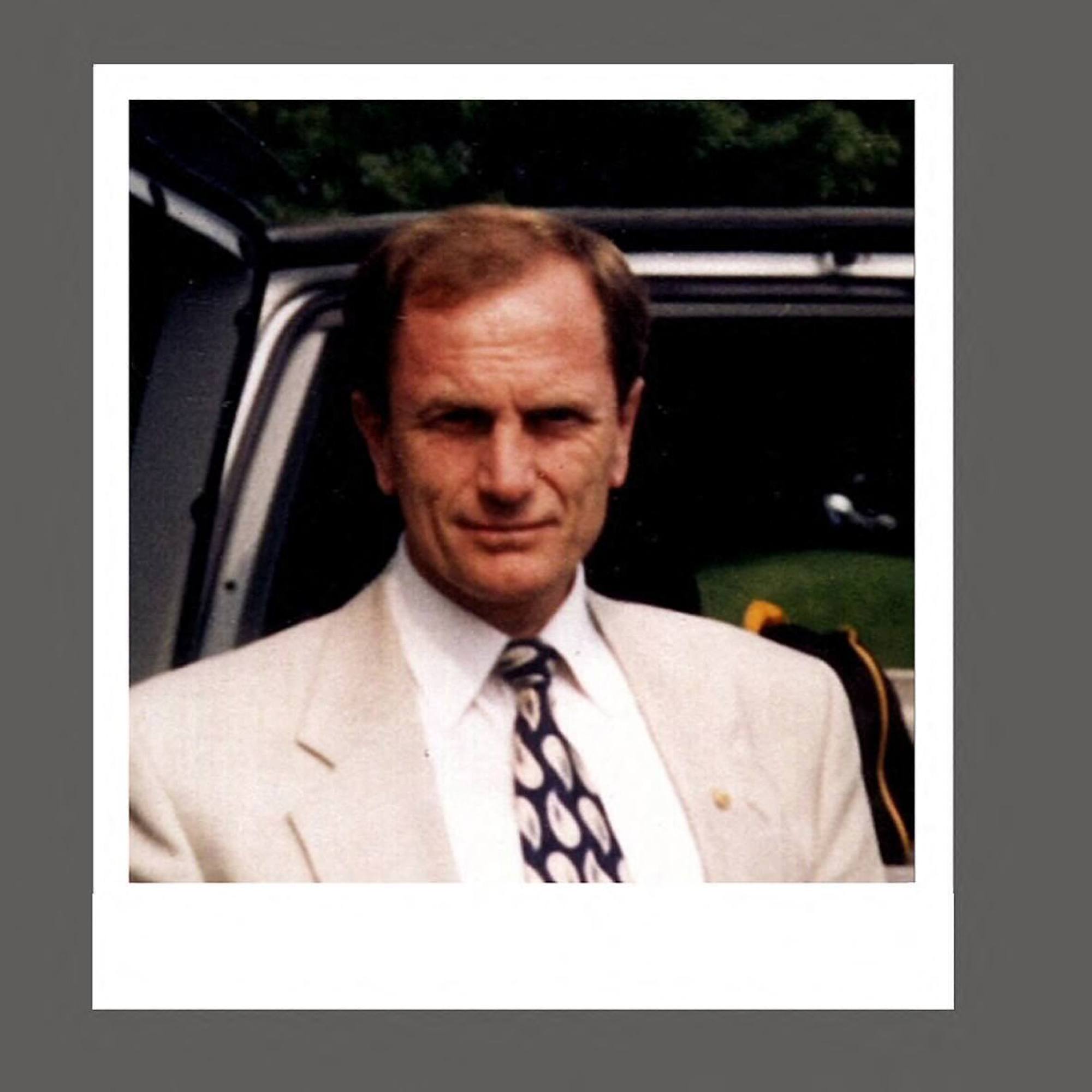

But Ngo had never been charged with a crime until after Newman’s death; rather, he was a poster boy for multiculturalism and immigration in Australia.

After arriving penniless in Cabramatta in 1982, he got to work building a business and community power base that earned him de facto leadership of Sydney’s Vietnamese community. He also founded Dan Viet, a popular Vietnamese-language newspaper.

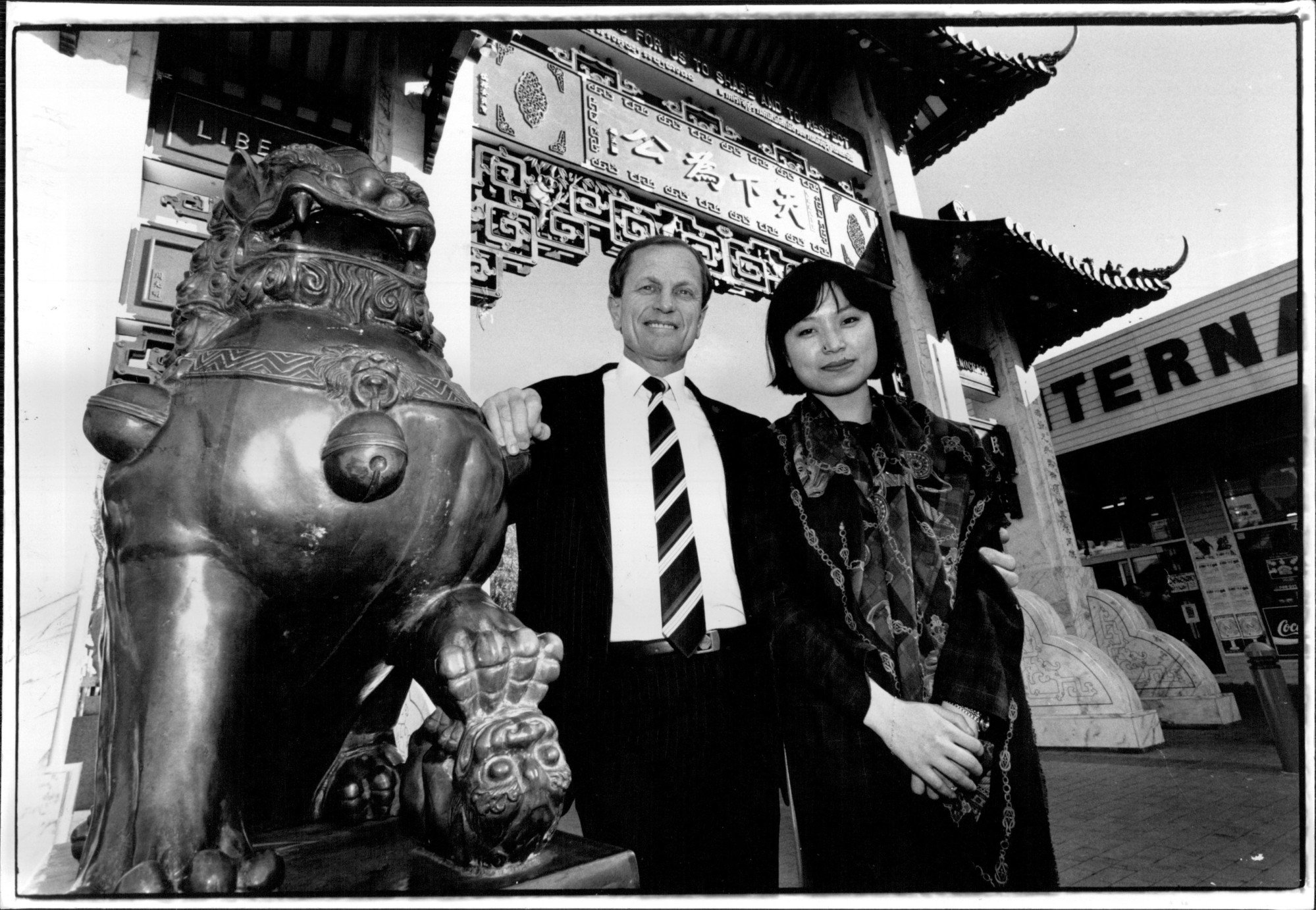

In 1987, Ngo was elected as a municipal councillor representing the people of Cabramatta on the Fairfield City Council. In 1990, he was elected deputy mayor of Fairfield – a remarkable accomplishment for an immigrant who could barely speak English eight years earlier.

Yet it wasn’t enough for Ngo. He wanted to join the political big league and dreamed of becoming the first Vietnamese-Australian elected to parliament. But one man – Newman – kept standing in his way, defeating him soundly at state elections in 1991 and denouncing him as a crime boss at every given opportunity.

Police would later allege that Ngo decided to kill his political rival after his loss at the polls and made four botched attempts on Newman’s life until he finally succeeded.

“I don’t know much about enemies, but I do know that Newman didn’t have many friends,” Ngo told police when they first interviewed him nine days after the murder, adding: “We had differences. I must stress I never liked the man.”

With Newman’s distraught fiancée unable to recall the face of the shooter or any details about the getaway car, Ngo was allowed to go about his business. Within six months of Newman’s death, he had assumed the presidency of the Cabramatta State Electoral Council of the Australian Labor Party – Newman’s political party – and was No 1 on the ticket and chief fundraiser for the party in the Fairfield council elections.

And so it appeared Ngo had got away with orchestrating an assassination – until initially reluctant witnesses began to cooperate with police, giving them the evidence they needed to charge him with first-degree murder in 1998.

After three years on remand and three trials – the first was aborted and the second ended with a hung jury – Ngo was found guilty of orchestrating Newman’s murder.

As a result of New South Wales’ Byzantine mandatory sentencing regime and the gravity of his crime – described by presiding judge John Dunford as an “attack on democracy” motivated by “naked political ambition” – Ngo was sentenced to life behind bars without the possibility of parole.

Case closed? Not quite. Ngo has always maintained his innocence, and to this day the shooter and driver remain at large.

David Dinh, a Vietnamese man who worked at the Mekong Club and who police accused of pulling the trigger, and Quang Dao, the alleged driver of the getaway car, were both acquitted during the third and final trial and remain adamant that Ngo could not have been involved in the crime.

“I know for sure that Phuong is not involved in that murder,” Dao said, claiming he used the alleged getaway car – a white Toyota Camry – to pick up his children at the time of the shooting.

In a 2008 documentary feature by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Four Corners news programme that raised serious doubts about the validity of Ngo’s conviction, Dao described how police offered to drop the charges laid against him and grant him clemency if he changed his story and gave evidence against Ngo.

“They said if I cooperate they would put me in [the] witness protection programme, not only me but my whole extended family, and I refused that,” said Dao.

“Cooperate. What did they want you to do?” Four Corners asked.

“Cooperate means like saying what they want to say, which is saying Tony and Phuong were guilty of the charge that they made up about them,” said Dao, referring to a third co-accused who worked at the Mekong Club and later turned state witness against Ngo, and whose real name was suppressed by a court order.

“I told them we have no deal. I don’t agree to do that.”

“The story of how Tony changed his evidence and had his murder charge dropped is extraordinary,” Four Corners reported, saying he only changed his mind after his teary-eyed mother visited him in prison.

“Dear Quang,” Tony said in a tape recording played to Dao and later obtained by Four Corners in which he tried to explain why he became a police snitch, “I suppose you will be surprised when you hear my voice in this tape. Perhaps you will be very angry but please listen to what I have to say to you.

“Let me explain. Mum was crying, and she said, ‘Tony, if you still love your mother, you have to listen to the advice’. I told my mother, ‘Mum, I cannot do it, because if I did, I will jeopardise other peoples’ lives, especially Quang and his family. My conscience doesn’t allow me to do that.’

“My mother said, ‘If you don’t listen to me, I will take my life’.”

Dao says Tony was forced “to choose between his mum, the person who raised him, and two others, who were just acquaintances. And knowing the pressure his mum was under after he heard [her] threatening to kill herself if he didn’t do what the Crime Commission wants, I feel more sorrow for him than anger”.

But Dinh, who spent two years in prison before he was acquitted, was less forgiving. “How can someone sit there, and you work with and see day in and day out, make up all these bullc**p stories,” he told Four Corners, fighting back tears.

After the Four Corners investigation was aired on national television, the New South Wales government commissioned a multimillion-dollar inquiry into Ngo’s conviction, headed by retired judge David Patten. But it didn’t go Ngo’s way.

“The Crown in a criminal trial has very few opportunities to ‘choose’ its witnesses. So it was in this case that it became obliged to call witnesses who had themselves engaged in criminal activity,” Patten wrote in his 210-page report, adding: “It was likely that the honesty and reliability of such witnesses would be severely tested in cross-examination and indeed it was.”

Patte n also highlighted the fact that Ngo chose not to testify at his third and final trial after his lawyers advised him on “the risk of exposing himself to cross-examination”.

Patten discounted questions raised by Four Corners that suggested police may have planted the murder weapon: a rare .32 Beretta police divers uncovered in the nearby Georges River four years after Newman’s death – and only 20 minutes after the search began.

The Beretta was so corroded that ballistics experts were unable to conclude that it was the actual murder weapon and prosecutors had to rely on an expert in Germany to testify against Ngo.

Police had alleged that Ngo dumped the murder weapon in the Georges River half an hour after Newman’s murder – a conclusion they reached after triangulating Ngo’s mobile phone record, the first time this investigative technique was used in Australia. But Four Corners obtained new research that showed “grey areas” near mobile phone towers that cast doubt about Ngo’s whereabouts after the murder.

Ngo’s lawyer later argued in court that “the idea that Mr Ngo would arrange contract killers to kill Mr Newman and then take an active role in the disposal of the murder weapon is such an unlikely proposition that I can scarcely believe the prosecution had the audacity to run it”.

Pat t en also shot down this argument, saying that irrespective of the phone records and use of triangulation technology, “Mr Ngo’s supporters had sought to create a major issue out of what seems to be a relatively minor feature of the case” given that Ngo had admitted to being in the vicinity of the Georges River after Newman was killed.

Patten concluded he found nothing that “casts doubt upon or raises a sense of unease in respect to the conviction of Mr Ngo” or suggested the police investigation into Newman’s murder was not conducted “thoroughly or competently by police officers dedicated to the task”.

Homicide squad chief Kaldas commended the inquiry for its findings. “Police are of the firm view that this was one of the most compelling briefs of evidence to go before a jury and they have no doubt whatsoever that the jury reached a correct verdict of guilt against Phuong Canh Ngo,” he said, describing the case as “one of the most scrutinised investigations in the state’s history”.

But Leslie Smith, a retired applied scientist mentioned in Patten’s report as one of Ngo’s most steadfast supporters, believes the retired judge’s findings were incomplete since he failed to take into account key discrepancies in the trials. And there is good reason to listen to him.

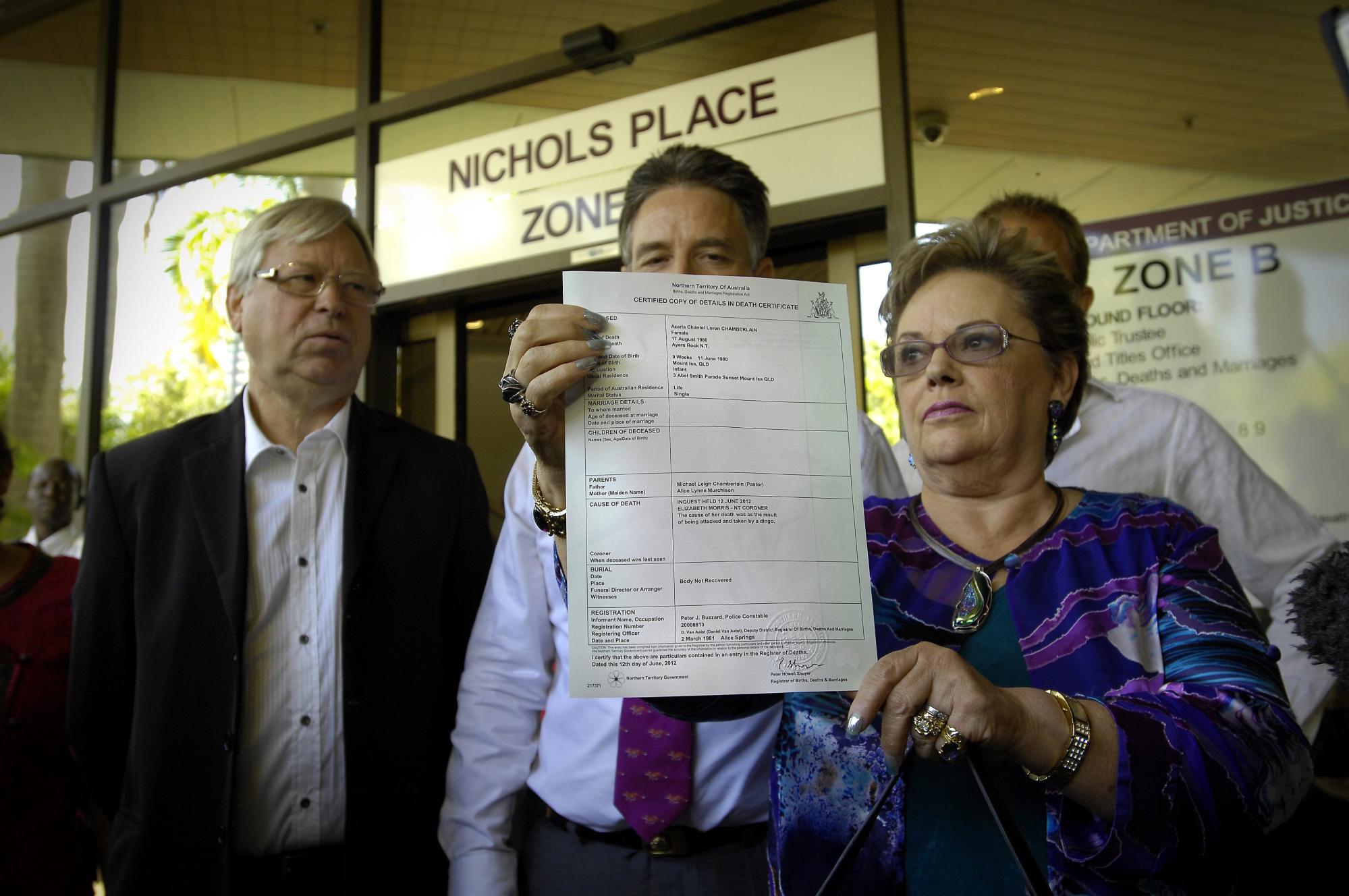

In 1982, a woman named Lindy Chamberlain was found guilty of murder after her nine-week-old baby, Azaria, disappeared during a camping trip in the Australian outback.

Chamberlain claimed Azaria had been taken by a dingo (an Australian wild dog) while sleeping in a tent but a jury found her mother guilty of murder after a stain found on the dashboard of her car was identified by a forensic pathologist as blood containing haemoglobin that is present only in infants less than six months of age.

Then Smith stepped in, drawing on his decades of experience to establish that the stain was, in fact, a “sound deadener” accidentally sprayed on the inside of the car during the manufacturing process.

Coupled with the discovery of Azaria’s jacket near a dingo den, Smith’s observation gave Chamberlain’s lawyers the evidence they needed to reopen the case and prove their client’s innocence.

A decade after Chamberlain was exonerated, Smith was asked by a friend to look into Ngo’s case, and what began as a passing interest turned into an obsession that consumed thousands of hours of the scientist’s time.

“I have combed through all the court transcripts, the committal hearings, inquests and inquiries and I sat through the third trial,” he says.

“I also visited Phuong in prison twice. It gave me an understanding of the case I think few other people have. I became particularly concerned about some discrepancies in the evidence used by the prosecution, especially sudden switches in context.”

One element Smith finds particularly troubling is the evidence of two witnesses whose identities have been suppressed by a court order and who we will name Witness 1 and Witness 2.

During the committal hearing before the first trial – a court date where prosecutors present evidence to the magistrate – a police running sheet presented by the prosecution claimed Ngo gave Witness 1 a photograph of Newman, and asked Witness 1 to find someone to do “nasty stuff” to the politician.

Some time later, Witness 1, who it was claimed worked at a Vung Tau fish shop behind the Mekong Club at the time, offered the job to Witness 2 as he was delivering detergent to the shop. Witness 2 subsequently turned down the offer but Ngo’s intent was clear, the Crown alleged.

“The problem,” Smith says, “is that the Vung Tau fish shop didn’t open until nine months after Newman was shot, and police knew that. We have two witnesses who gave evidence about a conspiracy to commit to murder at a place that didn’t exist, so it appears the conversation was fabricated.

“What was the source of this coincidental evidence? I have come to the view that police acted as a conduit while these witnesses fabricated this evidence and the reason they did that was that police leaned on them because both these witnesses were dealing drugs and were offered a deal to testify against Ngo.

“If there was a pattern of misconduct that runs through all three trials, where police placed witnesses under surveillance, identified weaknesses and made offers of clemency in exchange for accounts of the Crown’s hypothesis of how and why Newman was murdered, then the entire process was fraudulent.”

Smith says he attempted to present this information to the inquiry into Ngo’s conviction but found there was no interest in anything he said.

“If you read the findings of the inquiry,” he says, “you will see Judge Patten did not call these two witnesses who would have been most able to assist him. He declined to hear them and it is very clear to me why: the authorities would prefer if Ngo stays in prison and this case goes away.”

A retired journalist who covered the crime beat for the Fairfield Champion and other local newspapers in western Sydney for nearly a decade, Carlotta McIntosh attended all three of Ngo’s trials. And she clearly remembers the moment when the conversation between Witness 1 and Witness 2 was first presented during a pre-trial hearing.

“The police said they had an incriminating conversation from April 1994, about five months before the murder, where [Witness 1 and Witness 2] discussed killing Newman and allegedly [Witness 1] was asked to do so by Ngo,” she says.

“Phuong was in the prison box and whispered to his lawyer that the fish shop did not open until the following year. His lawyer subsequently raised the point. The prosecutor still used that evidence at the first trial but by then the conversation no longer took place at the fish shop but at a different address.”

McIntosh, who is currently writing a book about Ngo’s conviction and how she “came to believe there was something wrong” with the trials, says that “the narrative about Newman being a crime fighter and upstanding member of the community and which painted Phuong as an evil crime boss was very simplistic.

“I met Phuong many times before the shooting. He was charming, very smart, a fast learner, very good at languages, a political animal. He didn’t need to kill to get what he wanted. He negotiated, bargained and struck deals across party lines.

“Claims that he was some kind of drug lord or head of the 5T gang in Cabramatta were absolute nonsense. I covered the courts for years and there was never a scintilla of evidence that he was involved in crime.

“Newman,” McIntosh continues, “was a different kind of person. He was tyrannical, a bully, both verbally and physically, an intimidating man and he terrorised his staff. The only thing that really seemed to bother him was the growing number of Vietnamese living in his area.

“Bob Carr, who was then leader of the Labor Party in New South Wales, was very worried about the bad publicity Newman was causing and wanted to replace him at the next election.”

The accepted narrative, she says, led to Ngo’s alleged motive and the harshness of his sentence.

“When Phuong was sentenced the judge talked about an assault on democracy, and that was what put him in the worst category of criminals. But it is simply not true because everyone close to Phuong knew he had given up on becoming a member of the lower house [of parliament where Newman held a seat] and wanted a seat in the upper house instead.”

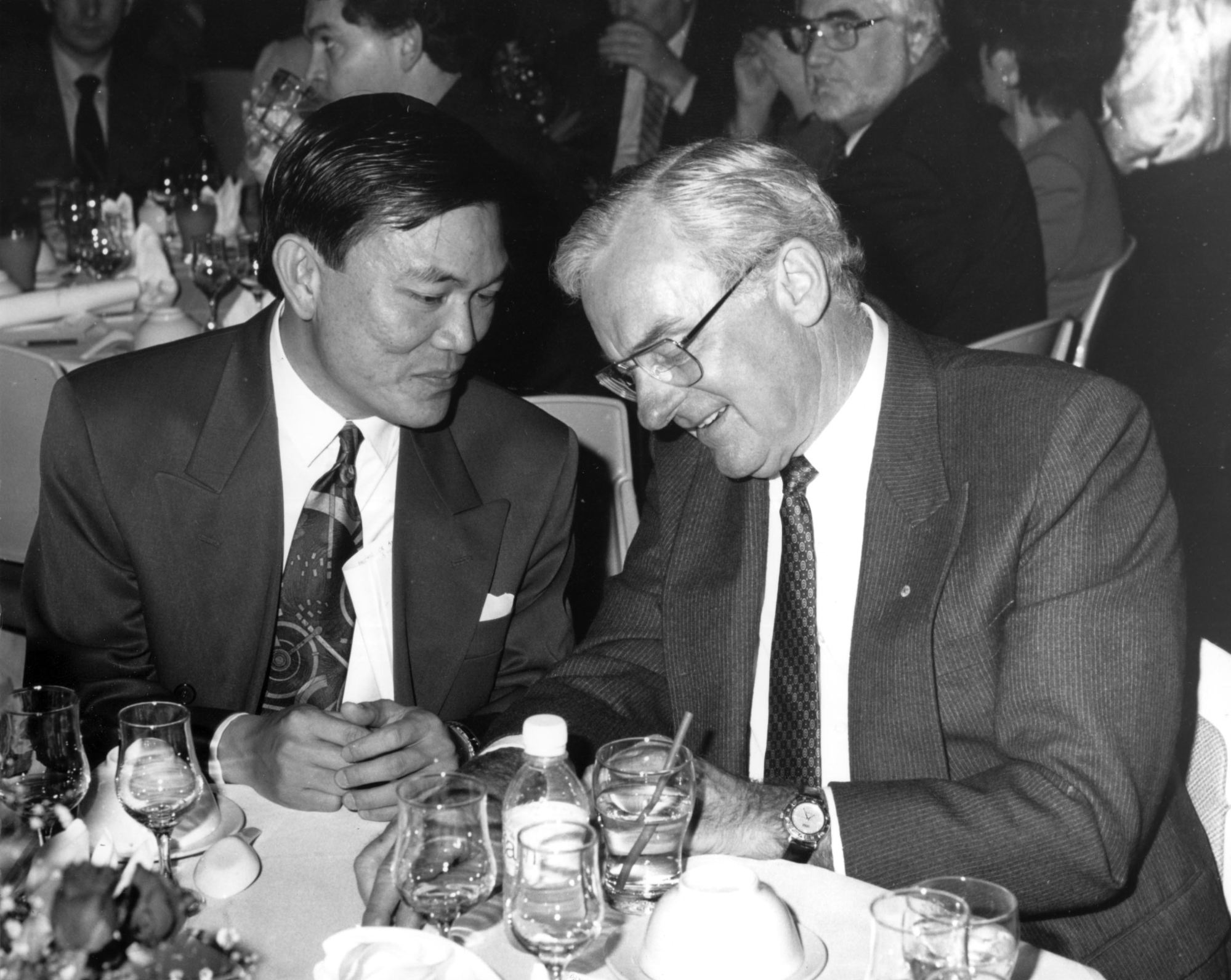

A police running sheet detailing a conversation between Ngo and the then New South Wales Labor Party general secretary, John Della Bosca, at a restaurant in Sydney’s Chinatown on the day of Newman’s murder appears to substantiate McIntosh’s opinion.

“Newman was mentioned during lunch,” the running sheet reads. “Della Bosca suggested that Ngo run against Newman in the next election. Ngo said words to the effect of ‘No, I’ve given my word to Newman that I won’t run for the legislative assembly as member for Cabramatta, [he] would not oppose Newman in pre-selection’.”

McIntosh says the meeting and numerous other pieces of evidence that are on the public record “completely destroy” Ngo’s apparent motive for the crime.

“If I was on the jury, I would not have found him guilty beyond a reasonable doubt,” she says. “Sure, there was loads of evidence against him but that doesn’t mean the evidence was correct. Most of it came from the Crime Commission, which journalists can’t report on. It’s all shrouded in secrecy, like an inquisition.”

Questions about Ngo’s apparent motive are central to a campaign by a small but determined number of supporters urging the attorney general of New South Wales to launch an inquiry into Ngo’s sentencing.

“As Australians, we claim the moral high ground about our record on human rights. Yet when it comes to sentencing laws, New South Wales is now seriously out of step with the international community and its human rights initiatives,” wrote John Anderson, Felicity Wardhaugh and Daniel Matas, lecturers in law at the University of Newcastle Legal Centre, in an opinion piece published by The Sydney Morning Herald in 2013.

“When the New South Wales Supreme Court sentences an offender to life without parole or the possibility of review, then arguably there has been a breach of Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” the trio wrote. “No penal system is to be purely retributory in nature.”

The view that it’s time for New South Wales to abolish mandatory sentences, trust in the wisdom and experience of its judges and honour Australia’s commitments to progressive human rights is shared by many of the state’s most eminent legal minds, including retired High Court judge Michael Kirby and Nicholas Cowdery, a former director of public prosecutions for New South Wales.

In his 2019 biography, Frank and Fearless, Cowdery wrote that, “Mandatory sentencing laws stop judges and magistrates from doing an important part of their job – making the punishment fit the crime and the criminal and achieving justice”.

Even Dunford, Ngo’s sentencing judge, who died in 2003, believed Ngo’s case deserved future review: “This is not a case where I believe he necessarily needs to be kept in custody for the whole of that time, and if I had the power to do so, I would fix a non-parole period,” Dunford wrote in his sentencing remarks.

He added that during Ngo’s three years on remand, when the trials were taking place, Ngo had been a “model prisoner” who had “assisted young prisoners” and set up the Fairfield Drug Intervention Centre.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of Ngo’s incarceration, meaning he has already served a life sentence, including a 13-year stint at the Goulburn “supermax” Correctional Centre, the toughest prison in the country, after prison officials linked him to a gang called W2K, or Willing to Kill.

He has not had any opportunity to make his case for release since 2014, when he lost a final bid to appeal his life sentence in the High Court. Ngo is now 64.

“The public still believes the myth that Phuong was a crime boss so it doesn’t look good for him,” says McIntosh. “He has exhausted all avenues for appeal so unless Leslie [Smith] comes across a convincing piece of evidence like he did with Lindy Chamberlain, by the time Phuong dies he will have spent two life sentences in jail. Even if he is guilty, does he deserve that?”

The office of the Attorney General of New South Wales Michael Daley did not respond to inquiries about the campaign to review Ngo’s life sentence.

Corrective Services New South Wales refused to facilitate an interview with Ngo “for a range of reasons, including limiting opportunities to re-traumatise victims and their families”.

Newman’s family would likely agree. “Phuong Ngo wanted the upper house,” Newman’s half-brother, Peter Naumenko, told a media pack after the verdict was announced in 2001, “Now he’s got the upper bunk. I hope he enjoys it.”