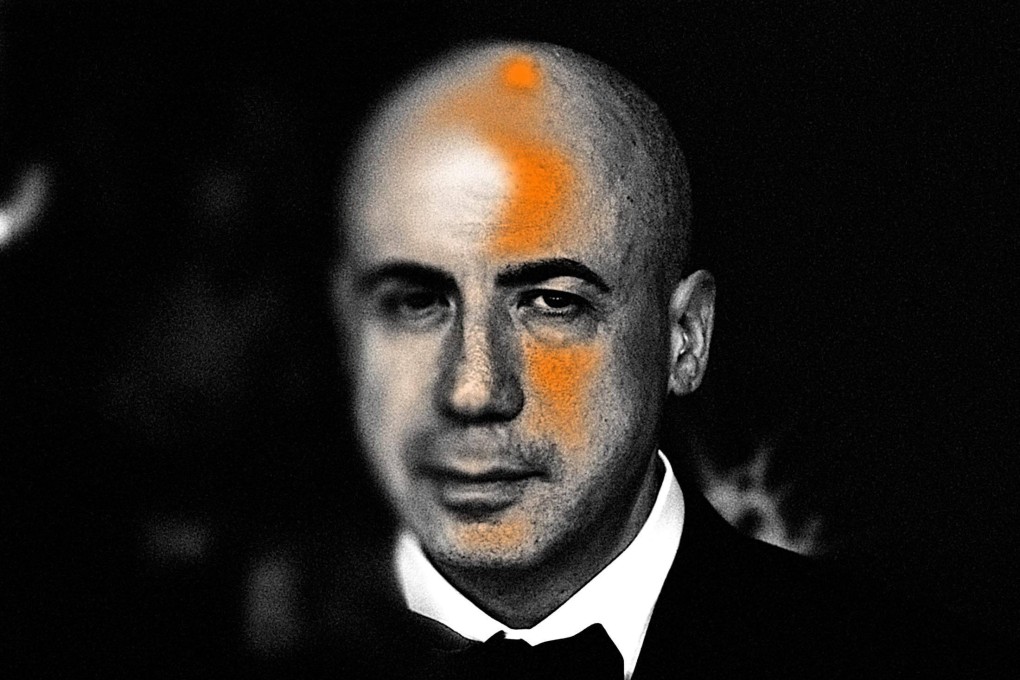

Russian billionaire investor in Facebook, Twitter and SpaceX on the defensive over funds from a pro-Putin oligarch that helped him get started

- Yuri Milner got rich investing in successful Silicon Valley start-ups, with much of his seed money linked to Russia, but now he is distancing himself from Putin

Starting in the early 2010s, getting an invitation to Yuri Milner’s chateau in Los Altos, California, meant you’d made it into Silicon Valley’s most exclusive of exclusive circles. Milner is known for placing what proved to be extremely lucrative bets on Airbnb, Alibaba, Twitter, Facebook and other start-ups – and for being a prolific patron of the sciences.

He was friendly with the late Stephen Hawking and is known to socialise with Mark Zuckerberg and actor Edward Norton. When Milner hosted a watch party for the HBO series Westworld, Google co-founder Sergey Brin showed up.

Milner is also an exceedingly wealthy Russian who started his venture capital career with help from Alisher Usmanov, an Uzbek-born metals magnate close to Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin.

Most people who know Milner have shrugged off his connection to a pro-Putin oligarch. Milner’s business – early-stage tech investing – is far removed from the world of the Russian oligarchs who got rich by acquiring state assets at dirt-cheap prices. And the money from Usmanov, as well as from Russia’s state-controlled VTB Bank, came during the presidency of Dmitry Medvedev, when the Obama administration in the United States was urging a “reset” of Russian-American relations.

But now, as Putin’s army is shelling Ukrainian cities, Usmanov and VTB are on sanction lists. And Milner is on the defensive. “I cannot go back and change history,” he says during several hours of Zoom interviews. “I cannot change the fact I was born in Russia. I cannot change the fact we had some Russian funds.”

Milner’s non-profit Breakthrough Prize Foundation and his venture capital firm, DST Global, have both released statements condemning “Russia’s war against Ukraine, its sovereign neighbour”, as DST puts it. A Breakthrough Prize Foundation statement, credited to chairman Pete Worden, referred to Russia’s “unprovoked and brutal assaults against the civilian population”. Milner and his organisations have pledged US$14.5 million to fund humanitarian efforts.